I am in the Atherton Tablelands in Queensland, Australia. I catch just a flash of colour high in the trees; one of this country’s wonderful parrots. I am reminded of a treasured book at home: Joseph M. Forshaw’s “Parrots of the World” exquisitely illustrated by William T. Cooper (Doubleday, 1978.)

At an information centre near Malanda, I have a leisurely coffee and spot a DVD for sale of a documentary by Sarah Scragg entitled “Birdman: The art of William T. Cooper.” Quite a coincidence! But then… maybe not. It turns out that this genius ornithological illustrator was Australian who lived and worked just around the corner!

The film briefly documents Cooper’s artistic life into his eighties but concentrates on him creating some thirty paintings for his last exhibition. It was filmed over the two years it took him to produce these works. It was fascinating to watch this modest and kindly man bring to life his subject matter on canvas. Cooper was completely likeable, described by Sir David Attenborough as ‘the best ornithological illustrator alive. You cannot better this. This is it!’ Sure is!

Cooper started his career as a self-taught landscape and seascape painter. He illustrated his first bird book in 1968 and, with Foreshaw, published Parrots of The World, Birds of Paradise & Bowerbirds of The World, Kingfishers of the World, definitive works on Turacos, Bee-eaters, Hornbills and Pigeons of Australia. He must have walked the same tracks as I did through the Tablelands.

He called himself a professional bird illustrator. It was his life, his passion and his daily work. His output was prolific. Over 45 years Cooper made hundreds of astonishingly accurate and beautiful illustrations and paintings of birds. In the film, he states that as a child “birds drove me insane.” I know exactly what he means. That total absorption in the study of amphibians and reptiles is similarly an insanity for me. I recognise that ‘insanity’ – that ‘love’ – at play in his work. The birds and backgrounds are perfect.

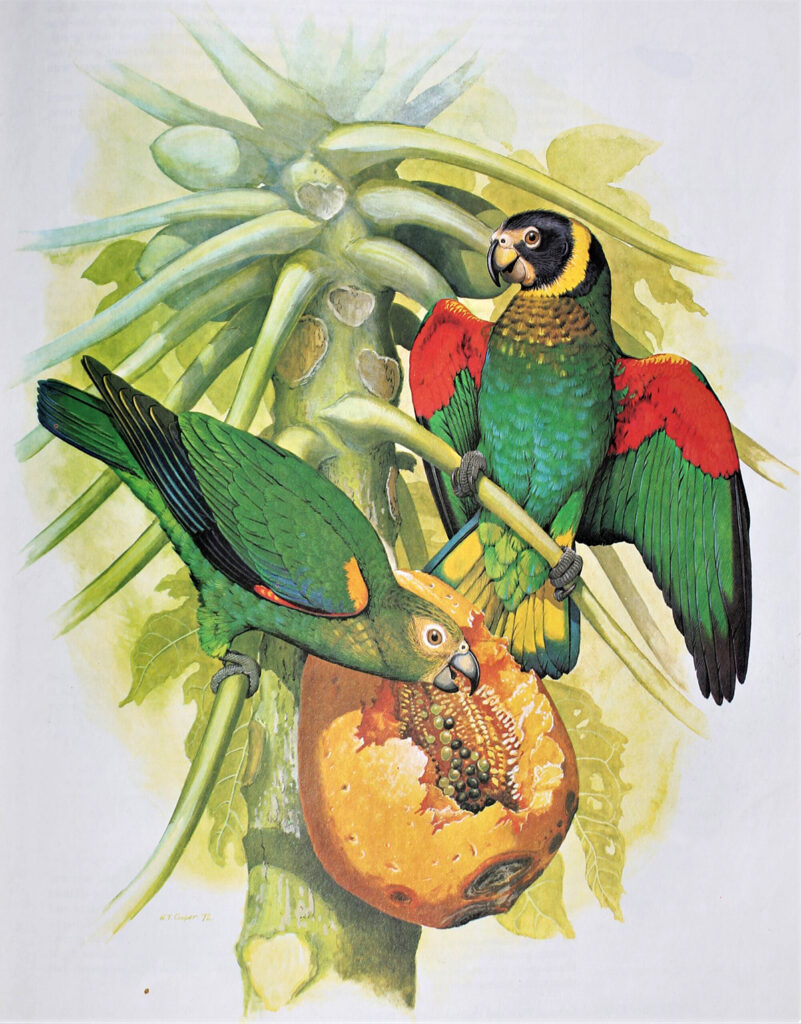

The film shows Cooper collecting reference material for the backgrounds to his birds. He shot fruit down from the canopy with a powerful air rifle. He brought home lichen-covered boughs from the forest floor. Latterly, digital photography replaced his thousands of sketches of background landscapes and wildflowers. He was rare among illustrators in that he would travel abroad to sketch as many of his subjects that he could in their habitats. Often a zoo visit would have to suffice. This practise, he explains, enabled him to put that final layer of accuracy into his birds; their ‘jiz’, their essence, the characteristics that are unique to each species. His studio included drawers filled with bird skins, feathers and much more. This complete dedication to accuracy, not only in the subjects but also in the backgrounds too, makes him one of the foremost scientific Illustrators of all time. Attenborough describes the difference between Cooper’s scientific illustration, where points of identification are necessary, and the paintings that he did for exhibitions. He could be free from science then and his work takes on a liveliness not seen in his book plates. However, as evidenced by the parrots shown here, he managed to make his scientific illustrations vibrant too and Attenborough acknowledges this as one of Cooper’s greatest skills.

As I watch Cooper at work and listen to his commentary I can’t help noticing the similarities between his working methods and mine. There is dedication to accuracy. There is collection of background materials and photography of subjects for reference. He uses transparent overlays to test ideas. With a mirror he can check composition and symmetry. He speaks of often being dissatisfied with his work and will destroy the output of days if it does not reach his exacting standards. But there the similarities end. I can only stand in Cooper’s shadow. I only work in one medium whereas Cooper is master of all. My output is limited and I’ve hardly ever sold my work. Quite simply, I finally realise, I am not in the same league.

The film ends at the exhibition. Every painting was sold within ten minutes. Cooper states that he is pleased but appears genuinely embarrassed by his success and fuss people are making of him. He can’t wait to get back to his rainforest home in Malanda to enjoy a cup of tea on his veranda; brewed precisely for five minutes as set by a timer. What a guy!