I find Lillias August’s website. A painting called “Decommissioned” stops me in my tracks. Crudely sawn and distorted parts of firearms are arranged in a row. Does the shadow whisper of prison? A church window? It is exquisitely executed and, as an image, totally arresting. The why and how of this picture intrigue. This is beyond masterclass still-life watercolour. I haven’t seen Lillias August for years; it’s time to catch up.

Lillias’s paintings have been a permanent presence in my life. Her water colours of family homes and rural scenes hang on the walls of friends and relatives. Snippets of news about her successes reach me regularly. Her formal bio reads as you would expect of an accomplished, multi-award winning painter elected to membership – and current secretary – of the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours.

I meet Lillias at The Gallery in Holt, Norfolk where she has contributed to a very classy exhibition that showcases the work of a number of professional water colour painters. I ask her about her fascination for the Norfolk landscape. She tells me that its flatness and openness generate a feeling of comfort; there is an honesty here. Nothing is hidden. I put it to her that she has moved on. She agrees.

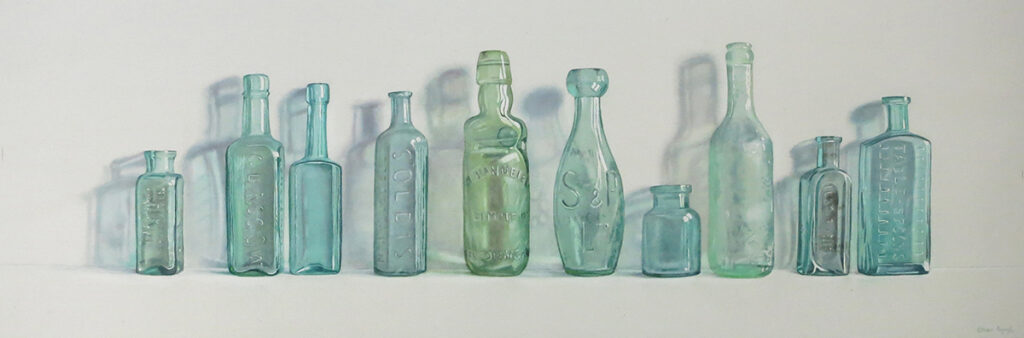

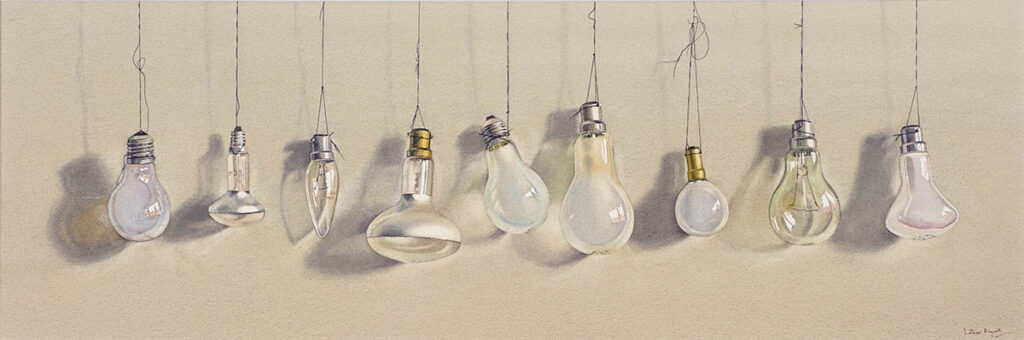

I am captivated by her more recent works. They are intricate and intimate studies of ordinary things presented in an extraordinary way. The horizontal theme clearly derives from her landscapes. I find that lines of empty birds nests (viewed from above,) empty antique green bottles (on an invisible shelf) and light bulbs hanging by threads (why… and attached to what?) together constitute a daring and ingenious approach to still-life painting. There is a delicious discord here. Subject and composition play off against total mastery of a very conventional medium.

Lillias gives direct and considered answers to my questions. I ask her about the provenance of her most telling and touching work; a commission with the title “Her shoes.” The response is untypically vague. Whatever the personal story, it will remain untold.

But how do we get from these beautiful all-in-a-row still life images to the parts of decommissioned guns? The answer lies in what Lillias’s bio does not mention: the fiesty – or even rebellious – side to her creativity. When at school, she painted and exhibited a picture of a hand crushing a stars and stripes coloured ball. Her head-mistress told her to take it off the wall. She admits that she still surprises herself by her choice of subject. In this vein, she is fascinated by how everyday objects become something else or even something sinister when their purpose changes. A local knife amnesty caught her attention. She took herself down to Ipswich police station where she was permitted to photograph not only an array of knives but also, and as a bonus, a cache of decommissioned firearms. She admits to a latent and strong desire to put a viewer of her work out of his or her comfort zone. With both “Decommissioned” and “Amnesty” she achieves this with flare and intelligence.

Jasper Johns said that “pop art” means to take something and add to it. Tongue in cheek, I ask Lillias if she would accept the label of “pop still-life water colour artist.” To my surprise she would. She concedes that this is the kind of painting that she really wants to do even if the result is not necessarily what people want to buy. Is the inner Lillias breaking out of a self-imposed mould? I hope so.