Talking Beautiful Stuff made an early morning start to share a little video of our four favourites from The Sculpture Garden 2020.

Yearly Archives: 2020

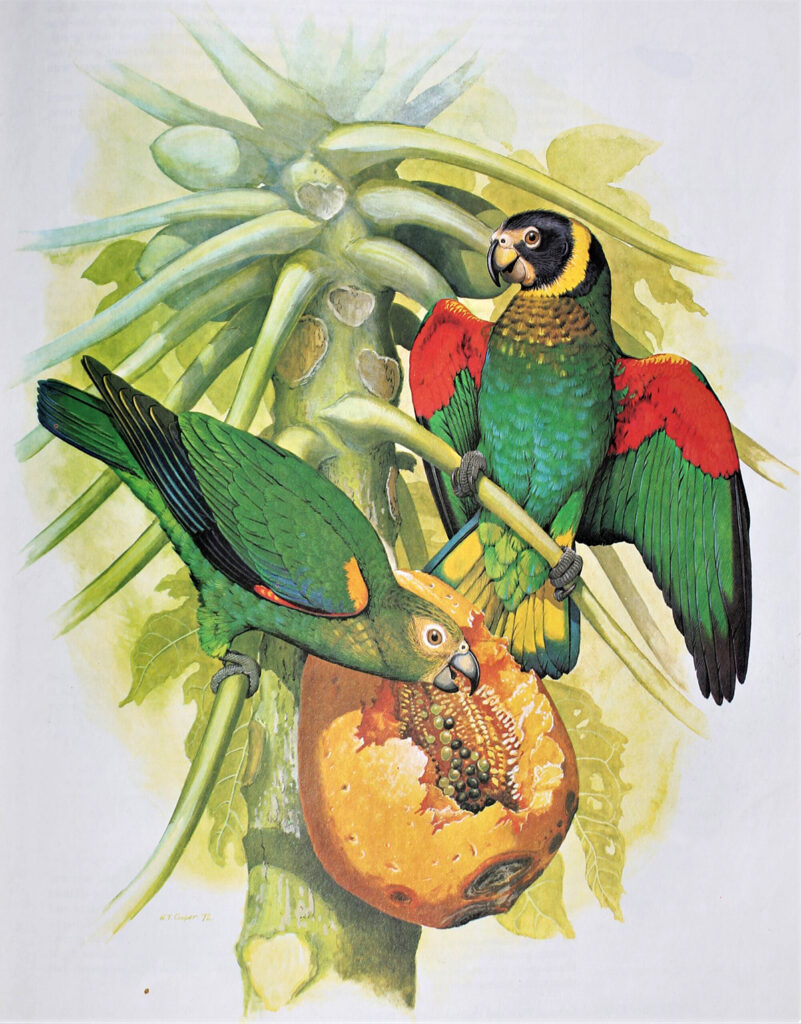

A tribute to William T Cooper, bird artist (1934 – 2015)

I am in the Atherton Tablelands in Queensland, Australia. I catch just a flash of colour high in the trees; one of this country’s wonderful parrots. I am reminded of a treasured book at home: Joseph M. Forshaw’s “Parrots of the World” exquisitely illustrated by William T. Cooper (Doubleday, 1978.)

At an information centre near Malanda, I have a leisurely coffee and spot a DVD for sale of a documentary by Sarah Scragg entitled “Birdman: The art of William T. Cooper.” Quite a coincidence! But then… maybe not. It turns out that this genius ornithological illustrator was Australian who lived and worked just around the corner!

The film briefly documents Cooper’s artistic life into his eighties but concentrates on him creating some thirty paintings for his last exhibition. It was filmed over the two years it took him to produce these works. It was fascinating to watch this modest and kindly man bring to life his subject matter on canvas. Cooper was completely likeable, described by Sir David Attenborough as ‘the best ornithological illustrator alive. You cannot better this. This is it!’ Sure is!

Cooper started his career as a self-taught landscape and seascape painter. He illustrated his first bird book in 1968 and, with Foreshaw, published Parrots of The World, Birds of Paradise & Bowerbirds of The World, Kingfishers of the World, definitive works on Turacos, Bee-eaters, Hornbills and Pigeons of Australia. He must have walked the same tracks as I did through the Tablelands.

He called himself a professional bird illustrator. It was his life, his passion and his daily work. His output was prolific. Over 45 years Cooper made hundreds of astonishingly accurate and beautiful illustrations and paintings of birds. In the film, he states that as a child “birds drove me insane.” I know exactly what he means. That total absorption in the study of amphibians and reptiles is similarly an insanity for me. I recognise that ‘insanity’ – that ‘love’ – at play in his work. The birds and backgrounds are perfect.

The film shows Cooper collecting reference material for the backgrounds to his birds. He shot fruit down from the canopy with a powerful air rifle. He brought home lichen-covered boughs from the forest floor. Latterly, digital photography replaced his thousands of sketches of background landscapes and wildflowers. He was rare among illustrators in that he would travel abroad to sketch as many of his subjects that he could in their habitats. Often a zoo visit would have to suffice. This practise, he explains, enabled him to put that final layer of accuracy into his birds; their ‘jiz’, their essence, the characteristics that are unique to each species. His studio included drawers filled with bird skins, feathers and much more. This complete dedication to accuracy, not only in the subjects but also in the backgrounds too, makes him one of the foremost scientific Illustrators of all time. Attenborough describes the difference between Cooper’s scientific illustration, where points of identification are necessary, and the paintings that he did for exhibitions. He could be free from science then and his work takes on a liveliness not seen in his book plates. However, as evidenced by the parrots shown here, he managed to make his scientific illustrations vibrant too and Attenborough acknowledges this as one of Cooper’s greatest skills.

As I watch Cooper at work and listen to his commentary I can’t help noticing the similarities between his working methods and mine. There is dedication to accuracy. There is collection of background materials and photography of subjects for reference. He uses transparent overlays to test ideas. With a mirror he can check composition and symmetry. He speaks of often being dissatisfied with his work and will destroy the output of days if it does not reach his exacting standards. But there the similarities end. I can only stand in Cooper’s shadow. I only work in one medium whereas Cooper is master of all. My output is limited and I’ve hardly ever sold my work. Quite simply, I finally realise, I am not in the same league.

The film ends at the exhibition. Every painting was sold within ten minutes. Cooper states that he is pleased but appears genuinely embarrassed by his success and fuss people are making of him. He can’t wait to get back to his rainforest home in Malanda to enjoy a cup of tea on his veranda; brewed precisely for five minutes as set by a timer. What a guy!

Big, brave and beautiful: the sculpture garden at Geneva’s Parc de la Grange

I meet Robin after work at the lakeside gate of Parc de la Grange. We’re catching up and checking out Art Genève’s latest big public sculpture project. We both acknowledge that we have never really explored this park despite it being the biggest – and most beautiful – of all Geneva’s green spaces. People are out post-COVID-19 picnicking. We stroll around. A low, soft and warm evening light picks out the carefully placed bronzes and installations. We chat about how Talking Beautiful Stuff, through covering lakeside Art Genève, has brought us to appreciate Big Public Sculpture and how under appreciated its creators are. So if a picnic with a lover or friend followed by a wander around a big, brave and beautiful sculpture park is your idea of fun and inspiration, then head on down to Parc de la Grange before the 10th of September.

One of the first works that our interest settles upon is Ida Ekblad’s “Kraken Mobil” (2020).

These are solidly built and pleasing to run a hand over. We can even sit on them; then we realise that they each are placed to give a different view of the park. All-in-one art and furniture for the great outdoors. Brilliant! We love the beach-towel stripes / nut and bolt / octopus combo. It’s whacky. It works.

The hidden jewel of the sculpture garden sits majestically and beguilingly in a leafy glade reflecting pretty much everything including the viewer. This is Trix and Robert Haussmann’s “Enigma” (2020); it takes some finding. It is a simple concept with a stunning and mesmerising outcome. If you don’t have time for the picnic, at least go and see this. BTW… kids love it!

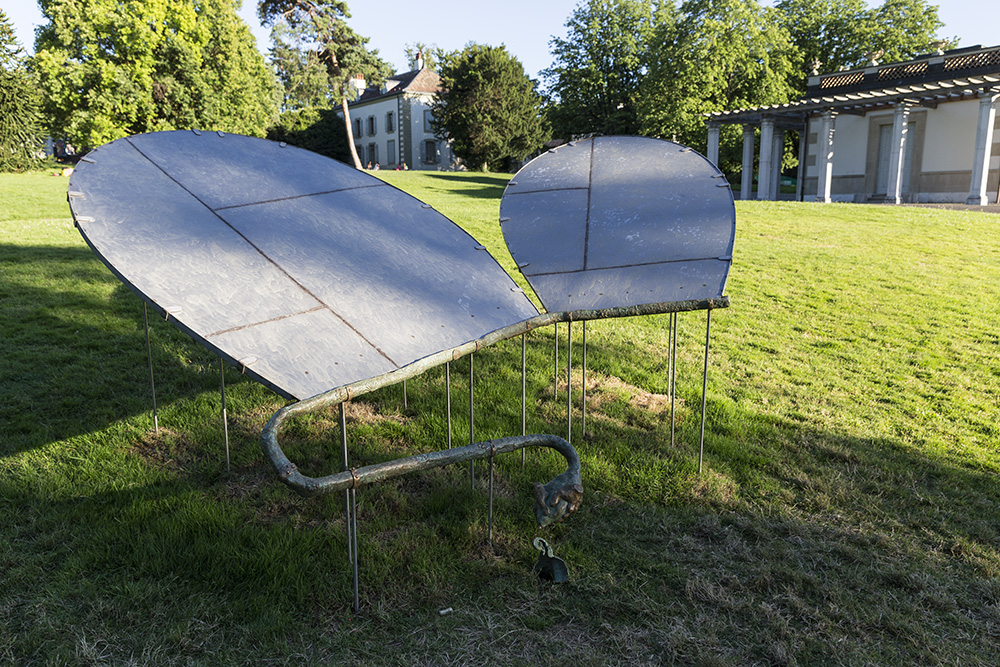

We come across Lou Masduraud’s “Moon Cycle Dew Fountain” (2020). As the name implies this is a mother-nature-mystic-new-age kinda thing. Two big oval panels capture rainwater (or dew) and funnel it into…

… a breast that is being hand-milked into an ear-like jug-like protrusion from the ground. Say what you like, it gets you thinking! BTW… kids are not so keen on this one!

Probably the bravest is Rosemarie Castro’s “Flashers” (1981). This a female sculptor’s comment on those men who get their kicks out of exposing themselves. From afar, the work appears sinister and sordid but somehow lightweight and crushable. Close up, the two hooded figures seem watchful but vulnerable; they are all too ready to snap closed that flimsy black mantle at the first sign of danger. Unfortunately the work fits so perfectly in a quiet tree-lined corner of a public park.

You will have gathered, we think this show is a well-located winner. It’s a freebee must-see. And give a thought to those barely recognised names that devote so much time and imagination to creating Big Public Sculpture.