This is a guest post by Angela Onikepe, who previously has talked about Square peg Frankfurt.

The Musée Barbier-Mueller sits discreetly on a quiet street just right after you scale the steps leading into the heart of Geneva’s Old Town. When you enter the museum, there is a muted and intimate atmosphere that envelopes you as you step into a world of classical and tribal antiquities. What particularly drew my interest was their collection of African masks; who’s to say, but I think I was looking for some remnants of home or some glimpse into the past of my native Nigeria. And, I was not disappointed.

It was the pieces from the ancient Yorùbáland (which spanned what is today Nigeria, Togo and Benin) that spoke to me in a language I understood. There was the 14th/15th century headdress from the Kingdom of Ifẹ̀ (Ilé Ifẹ̀ in Yorùbá), made of terra cotta, which exudes a regal essence befitting the elements on the mask identified with royal Yorùbá lineages.

Headdress, Ilé Ifẹ̀, Nigeria, 14th-15th century. © Musée Barbier-Mueller, Photo Studio Ferrazzini Bouchet.

In African culture, masks always served a tangible purpose and were deeply ingrained into the functional life of Africans. They were not decorations. Although their role was fundamentally religious, their roles also spanned several spheres in society, from social to familial, religious and educational and not to mention, their use also for entertainment purposes, social control and rites of passage. In sum, they were integral parts of the traditional society. Of course, each African country with its myriad cultures, expresses this element in its own unique way but the one common thread that binds all African masks is the fact that the mask itself, despite its real-life functionality, was meant to represent something that is, for all intents and purpose absent; a higher reality that is not readily accessible. The mask, in turn, becomes a symbol, rendered into a concrete and sensible form.

You can sense this robustness in history with Musée Barbier-Mueller’s collections of African masks. Indeed, this feeling emanates from all the collections in museum. The museum hums; almost as if you are placing your hand on a beating core as you encounter each item. But back to my quest to brush and nuzzle against my people’s past.

There was the Sceptre with a Horseman, also from the Kingdom of Ifẹ̀ which actually inspired Jean Paul Barbier-Mueller himself. Barbier-Mueller calls the Sceptre “the ‘Mona Lisa’ of our collection” and spoke about its “intense beauty and rarity… which furthermore testifies to the grandeur of a civilisation of which the whole of humanity could be proud.”

Sceptre with a Horseman, from Ilé Ifẹ̀, Nigeria, 12th-13th century. © Musée Barbier-Mueller, Photo Studio Ferrazzini Bouchet.

I did step away from “home plate”, so to speak, to see the other West African masks in the collection. One of the first masks that caught my eye was actually the Kanaga facial mask from the Dogon in Mali. Kanaga masks are the most well-known from the Dogon people and usually represent a bird known as the Kommolo Tebu. The masks owe their existence to a legendary and mythical hunter, who after subduing a Kommolo Tebu, fashioned a mask in its likeness. You cannot deny the majestic stance of a Kanaga mask; it demands attention.

Kanaga Facial mask, Dogon, Mali, 14th-15th century. © Musée Barbier-Mueller, Photo Studio Ferrazzini Bouchet.

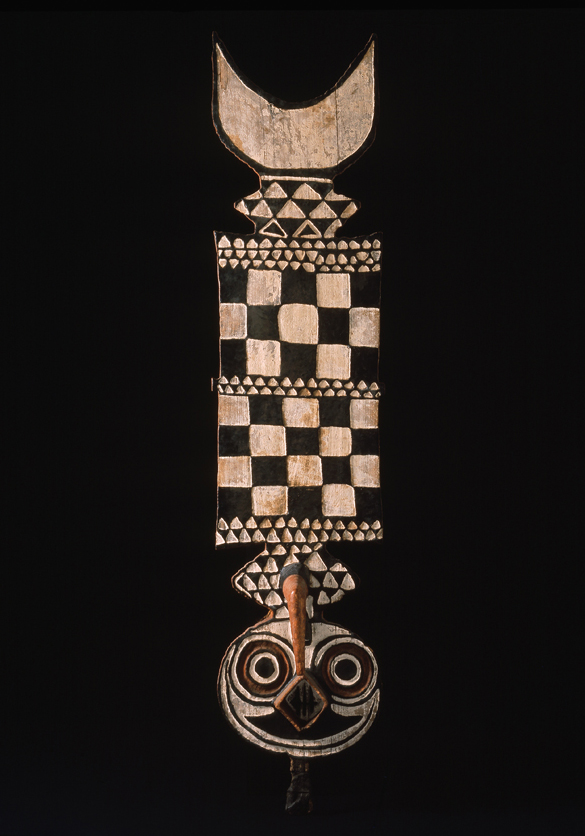

The Grand Masque from the Bwa in Burkina Faso, essentially made of leaves, feathers and plant fibers and meant to serve as a connection to the world of spirits, was not something that could be ignored.

Grand Masque from the Bwa (also known as the Bobo Oulé), Burkina Faso. © Musée Barbier-Mueller, Photo Studio Ferrazzini Bouchet.

I went to Musée Barbier-Mueller looking for the African connection; not only can you do the same, but your experience can also expand beyond my part of the neighbourhood to other parts of the world and pretty soon, after seeing the museum’s collections, you will find yourself humming right along with it.

The Barbier-Mueller collection did not start with its Yoruba “Mona Lisa.” The beginnings of its collection are rooted in the 1920s when Josef Mueller, at first interested in European art, moved to Paris and eventually started working with art dealers specializing in non-Western art. Mueller was so inspired, that he would go to flea markets with large empty suitcases, embarking on new adventures and new discoveries. Anne-Joëlle Nardin, the Deputy Director in charge of communication, explains the history behind the museum, mentioning the passion that fuelled Mueller’s sojourns. Years later, Mueller’s daughter Monique, would marry Jean-Paul Barbier who was also an avid collector. Upon Mueller’s death in 1977, the Barbier and Mueller collections were merged into the private 7,000-item collection that exists today. But the collection expands beyond Africa and Oceania; there are also objects from the East Indies and Greece, to name a few. Jean Paul Barbier-Mueller is, as Josef Mueller was, impassioned by the beauty of these pieces of history and a desire is to give the public access to them.

The museum’s exhibitions change twice a year. A new collection will be unveiled on October 17 where you can “Discover the Baga from Guinea.” See you there!