This is a guest post by Bonnie Golightly.

Yes, I love the Tate Modern in London. It lifts me up and makes my little beating heart sing.

I went south of the river to see the current Alexander Calder exhibition. I now understand why people say he redefined the notion of sculpture. Beautiful, beautiful, beautiful stuff. Trademark hanging mobiles turn slowly and majestically in imperceptible drafts. The lighting is brilliant; each mobile casts a complex evolving shadow on the high white walls and those equipped with mini-gongs let out the occasional calming chime.

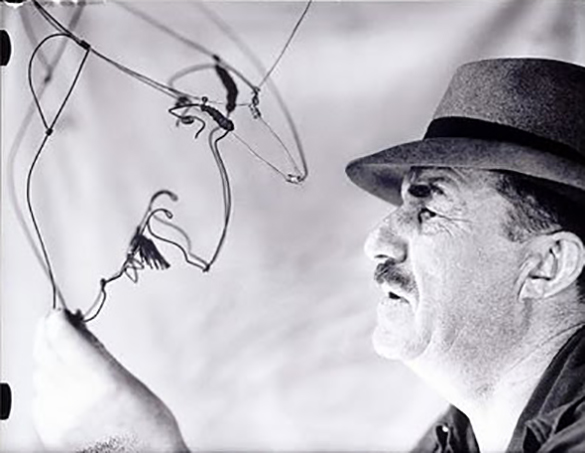

Alexander Calder, Antennae with Red and Blue Dots c.1953 Photo credit: Calder Foundation, New York / Art Resource, NY

I was mesmerised. As were many others. One lasting impression I have of this gorgeous exhibition is the vast Tate Modern rooms full of people, jaws agape, gazing up at Calder’s fabulous works. I would love to re-visit with a reclining chair to rest a while and soak it all up.

Room by room, I stepped though the creative history of this fascinating man. He was one original thinker! In the 1920s, he created a toy circus comprising little mechanical people and animals hence his interest in wire and mobility as a medium. He became fascinated by abstraction after visiting the studio of Piet Mondrian. However, his most astonishing early works were his cartoony wire portraits. He described this as drawing in space. It is beyond me how anyone could consistently achieve effective three-dimensional portraiture with only wire. One such portrait is of the painter, Fernand Léger. I love the contrast between the smooth facial outlines, the tightly coiled eyebrows and the stiff little bristly moustache!

Bravo, Tate Modern! I said to myself. Then I thought I would have a look at what else was on show and I found myself in the heart of the building, the enormous “Turbine Room” O….M…..G…..!!!!

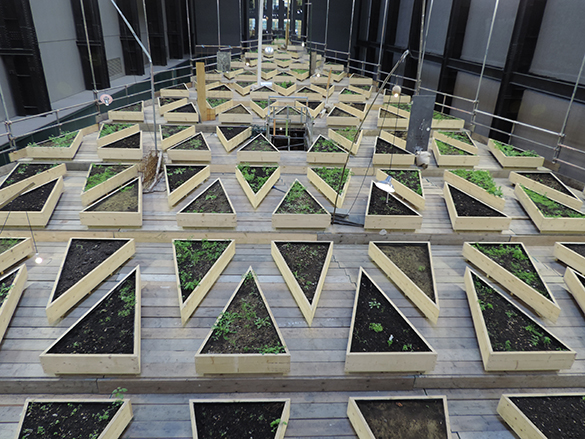

Now the Tate Modern blows me away with two huge scaffolding structures together supporting hundreds of what looks like triangular seed boxes. This is “Empty Lot” by Mexican sculptor, Abraham Cruzvillegas. The soil in each box is taken from parks, commons, healths or other sites all over London. They are watered and lit by a variety of whacky lamps. But not a single seed has been sown. What grows – and in some boxes nothing obvious is growing – is what is simply there. Just like an empty lot! Cruzvillegas has always had an interest in alternative means of building. He is inspired by the popular Mexican “self-construction” approach to home-making. He says “Empty Lot” is about hope and expectation referring to what may be constructed or what might grow spontaneously. The originality, grandeur and vision of the whole concept takes my breath away. I adore it.

I have a hope and expectation that somebody will send a photo of “Empty Lot” to Talking Beautiful Stuff in a few months time. Pleeeeeease!

Love the Tate Modern too!