I am standing on a bluff looking out over the Missouri River in North Dakota. There is a stillness and quiet here, only broken by the sound of Red-wing Blackbird song, Chorus Frog call and the distant sound of Canada Geese. Tears roll down my cheeks; I am here at last. A lifetime of reading, studying and dreaming about this place is fulfilled. This is a highpoint of my Western American road trip in the Spring of 2015.

Although now empty of human activity, on this very spot in 1832 stood the rough and ready, wooden-pallisaded trading post, Fort Clarke. Close by was the Mandan village of Mih-Tutta-Hang-Kush. The lives of the Mandan people was chronicled by two artists. George Catlin visited them in 1832 and Karl Bodmer travelled in the Prince Maximillian expedition of the Upper Missouri River in the winter of 1833-4. Prince Maximillian was an explorer and chronicler. His ethnologic notes with Bodmer’s watercolours made up his treatise on the Mandans, supplementing and corroborating the relevant parts of Catlin’s vast work on North American indians. These men brought to the outside world a visual picture of the native peoples of this region before white influence changed their culture and appearance for ever. They anticipated the tragic future of the Indians. I first saw their drawings and pictures when I was eight years old. They left me with a fascination for everything and anything to do with North American indians.

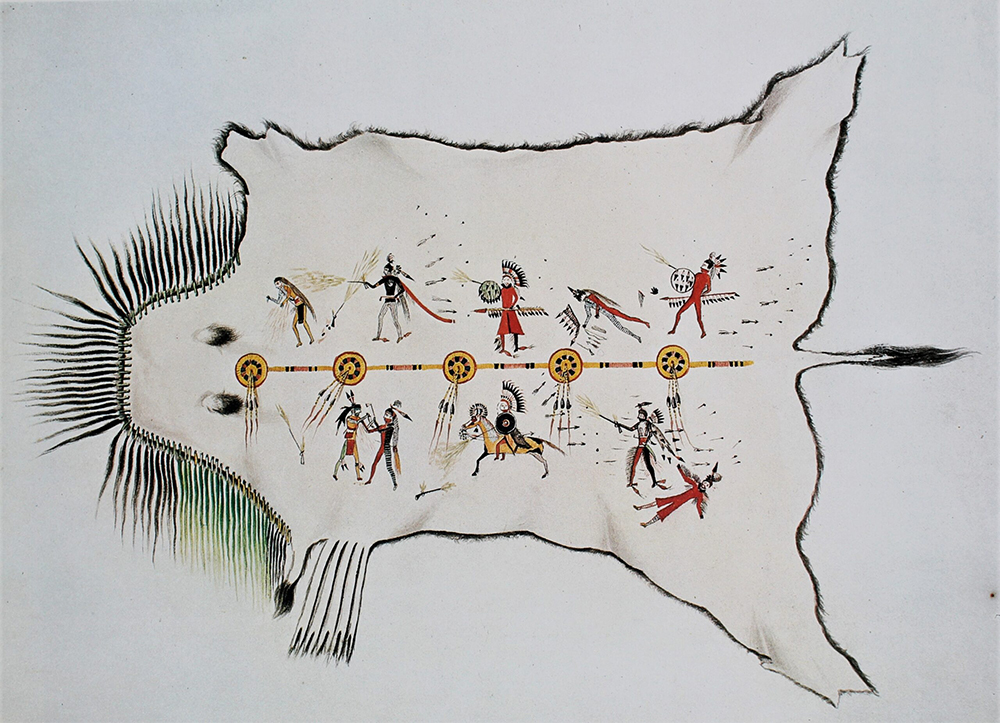

Mah-to-toh-pa (Four Bears), was a Mandan hero and head man. He was also a veteran of the O-kee-pa torture ritual that was witnessed by Catlin. In 1832 Catlin wrote “Oh! “horribile visu – et mirabile dictu!” Thank God, it is over, that I have seen it, and am able to tell it to the world”. He was the only white man ever to witness the O-kee-pa ritual of the Mandan. As a boy, I soaked up accounts of these horrors; they served only to deepen my interest in a people and a culture that was so far removed from anything I knew.

Bodmer was a watercolourist in the Victorian style and painted the landscapes that the expedition traversed, the wildlife and the peoples of the Missouri River. Catlin painted in oils and rendered fine drawings in pen and ink. He later painted many exquisite and historically important portraits of Indians from across America. His energy and his output was extraordinary. As you can imagine these guys were tough. They witnessed violence and murder and endured incredible hardships in order to feed their desire to discover and chronicle those discoveries. The journey up the Missouri by boat from St Louis to the Mandan country took three months! I just drove there, parked my car and wandered around to explore! We owe these men a great debt.

Artists who have also served as chroniclers include war artists, court artists and scientific illustrators. The reason for their creating is quite different from simply rendering a thing of beauty or an idea. They speak to us of the times and from the times in which they worked. Their work, unlike the written chronicle, has an inbuilt honesty to it. They are much less likely, or even able, to exaggerate or lie; for their reference sits before them and often with witnesses.

This portrait is a watercolour of a Minnetaree man, and friend of Mah-to-toh-pa, Pehriska-Ruhpa. He wears the ceremonial regalia of the Dog Band, the highest of the male orders. The Minnetarees had a shared culture with the Mandan and lived in villages further upstream. This portrait, later turned into an engraving, is considered to be the greatest ethnological rendering ever made. It accompanies a most detailed description of Pehriska-Ruhpa by Prince Maximillian.

At the time of the visits by Catlin and Bodmer, there existed only about 1,600 Mandan people. They had already been decimated by smallpox; a disease brought by white fur trappers and traders and to which the Mandans had no immunity. By 1836 the Mandan were all but extinct. Had these chroniclers got there just three years later one of the most extraordinary human cultures would be unknown today. And this brings me back to the O-kee-pa ritual.

In Letter No. 22 of his two volume work, Catlin chronicles, in full detail, the ritual where Mandan men voluntarily submitted to the most agonising tortures for the good of the people. It has to be among the most accomplished pieces of ethnologic observation and writing about the most bizarre ritual that our species has invented. It has changed how I think about mankind.

Bibliography

Bodmer pictures from: “People of the First Man. The first hand account of Prince maximillian’s expedition up the Missouri River, 1833-34.” Published by E.P. Dutton, New York, 1976.

Catlin pictures from: “Letters & Notes on the Manners, Customs & Conditions of North American Indians.” Published by Dover Publications Inc. New York, 1973.