I’ve been a space nerd since I was about seven, when my mum brought me to the planetarium in Stockholm. Mouth open, I looked up into this dome representing the night sky. I was immediately and totally captivated by all things space. I learnt among many other things that the speed of light is 300,000 km/second. The distance light travels in a year is the standard measure of distance in our universe. (For reference, our sun’s light takes 8.3 minutes to reach us!) Many of those distant stars are so many light years away that we perceive their light long after they exist. It’s something about space: it’s infinite immensity, it’s beauty, the countless unknowns, the big bang and, of course, the enthralling statistical certainty that, out there somewhere, other life forms are going about their business. Space remains the brimming fuel tank of my turbo-charged imagination. And this imagination morphed into excitement of unlimited scientific discovery when last year I found myself browsing through freely accessible of images from NASA’s Hubble telescope that has been orbiting our planet since 1990. Just take a look!

So how much of the night sky is captured by an image like this? It’s something like making a tiny hole in a piece of paper, holding this paper up at arm’s length and capturing a very high resolution image of whatever light comes through the hole.

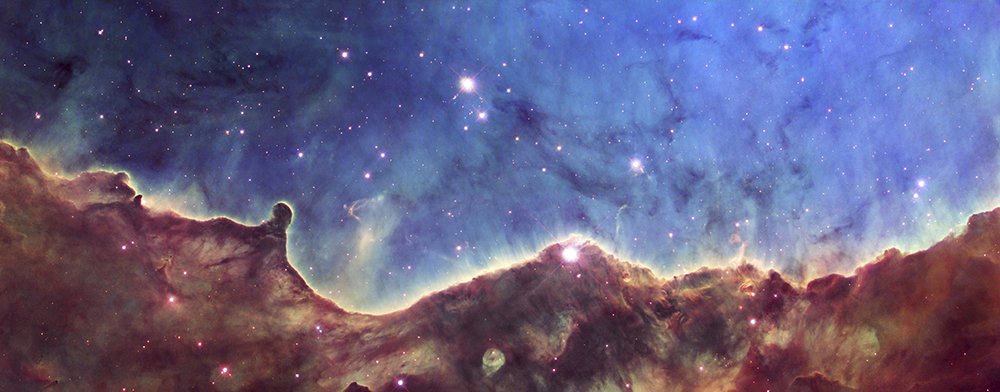

Hubble’s images of our universe are truly extraordinary. This has to be the most awe-inspiring beautiful stuff ever. Is it “art”? If so, who is the artist? The NASA photographer? Nature? A great creator? (Eek!) Here’s a Hubble image of the Carina Nebula.

In 2003, NASA decided that they needed even better and deeper images of the universe. (Well they would, wouldn’t they!) To do this they set out to use a massive high resolution infrared camera. In December 2021, they launched the $10 billion James Webb Space Telescope and have recently published some of the first images. Included is a very different view of the Carina Nebula.

The improved resolution of the Webb images is astounding and potentially bears enormous scientific fruit. For example, NASA scientists can identify even more stars that, however briefly, dim as a planet passes between the star in question and Webb’s camera. This multiplies many times over the number of planets that we know about that could potentially harbour life.

The real big trophy that Webb holds high takes the form of images made by light from stars 13 billion light years away. It is believed that these stars are the oldest in existence (if indeed they still exist!) and represent the immediate aftermath of the big bang. In other words, this image is created by light transmitted from the earliest universe and has been travelling from those stars for 13,000,000,000 years before being captured by the Webb telescope. Gosh! Images of the big bang! It’s time to grab a coffee with my buddy, Dan-Who-Knows-Stuff.

Dan-Who-Knows-Stuff once told me that there is mathematical proof that a parallel universe exists; an exact copy of us, our world and what we are doing. (Struggling!) He understands dark matter. (I don’t!) I ask him to give me a five minute tutorial on the big bang. This gets a huge smile. The story goes something like this. All matter in the universe was once contained in one lump. Nobody knows its dimensions. Possibly football size; possibly planet size. It was so dense that no light could be emitted from it. Then, for some reason, 13 billion years ago, it literally exploded and the fragments of that explosion accelerated rapidly away for a few thousand years to form our universe which, by the way, is still expanding but much more slowly. Many of the fragments are stars the matter of which can now transmit light. We know all this because light can be “dated;” it changes subtly the longer it has been travelling. We can also tell whether light is coming from a source that is moving towards us or away from us (the Doppler effect.) This is how we know that those stars, 13 billion light years away and seen for the first time by Webb represent the origin of our universe.

“Thanks, Dan-Who-Knows-Stuff!” I say. “But I have a question. If all the matter in the universe was contained in one lump, what was outside the lump?”

“I don’t know! That’s one of the two most fundamental and unanswered questions about the universe.” Says Dan-Who-Knows-Stuff.

“What’s the other question?” I ask.

Dan-Who-Knows-Stuff smiles. “What is time?” he says.