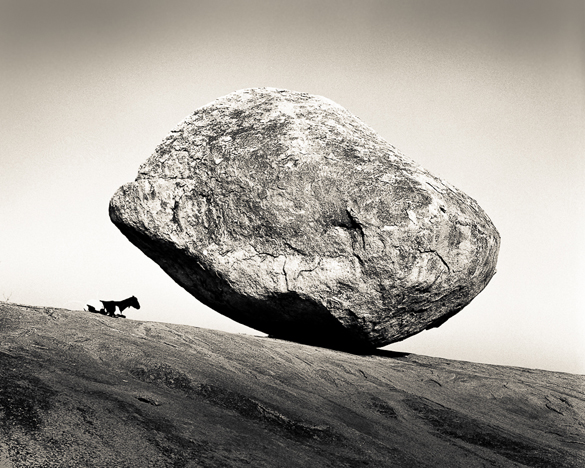

I am offered a friendly welcome. Quietly and modestly, I am shown about a hundred photographs taken from neatly stacked boxes. Mesmerising images of Himalayan villages, abandoned temples, animals, people, poverty and more pass before my eyes. There is a distinct style: the pictures are crisp, delicate and enduring. It is difficult to imagine the photographer’s presence in these scenes. I feel that if I were to retrace his steps, nothing would have changed. And this is the real deal: all the black and white photographs are developed by hand from medium-format film. I am overawed by the accomplishment and overdose on photographic beautiful stuff. I have difficulty finding questions that are not banal.

I am offered a friendly welcome. Quietly and modestly, I am shown about a hundred photographs taken from neatly stacked boxes. Mesmerising images of Himalayan villages, abandoned temples, animals, people, poverty and more pass before my eyes. There is a distinct style: the pictures are crisp, delicate and enduring. It is difficult to imagine the photographer’s presence in these scenes. I feel that if I were to retrace his steps, nothing would have changed. And this is the real deal: all the black and white photographs are developed by hand from medium-format film. I am overawed by the accomplishment and overdose on photographic beautiful stuff. I have difficulty finding questions that are not banal.

I have the privilege of meeting photographer Robert Ramser at his house in rural France. He is a calm, elegant man. The domestic atmosphere is unhurried and orderly. All around is beautiful stuff that speaks to his passion for the orient. Over Darjeeling tea, his life story unfolds. He grew up in Arles and watched the arrival there of the international photographic festival. He fell into the photographic scene, rubbing shoulders with Adams, Harbutt, Lartigue and McCullin. In 1974, the photographic neophyte moved to a small flat in Paris. A friend said he should visit the tiny Himalayan kingdom of Sikkim. He did. He returned to Paris with an idea of his future. The bathroom became a darkroom. He married Corinne, his Vietnamese neighbour.

Ramser feels at ease and indeed happy among the cultures and the people throughout Asia. He travels for up to three months at a time so immersing himself in his destination. However, photography is not necessarily the main aim; it simply serves to let him see beautiful stuff that he would not have seen, to meet extraordinary people that he would not have met and to stay longer than he would have in interesting places. He is not out to make a statement.

One of his widely exhibited series focuses on the secluded minorities of the “Forgotten hills” of the Ghizou and Yunnan provinces of south-west China.

In keeping with his fascination for Himalayan kingdoms, another series studies the Bhutanese concept of gross national happiness.

In Mumbai, he took refuge from the Indian heat in a small museum. He discovered a series of miniature paintings illustrating the ancient Panchatantra fables from the Mogul era. In explaining the background to his on-going Creatures of the Gods series, he says “In Hindu, Jain and Buddhist philosophies, every living thing is a soul incarnated in a material body. I was inspired by the exquisite manner these artists showed the presence and the dignity of the animals…”

Ramser has an exceptional photographic eye. He rarely takes more than 13 pictures in a day; he does not need to. He is not uncomfortable with digital photography but, for him, the infinite number of photos that this technology permits and the ability to review them immediately are a distraction. Time that would be best spent observing the subject is lost by checking the little screen on the back of the camera. In his own experience, if you take many photos of a subject, the first is often the best anyway. He says the most fulfilling moments of his photographic career are those precious seconds when, on releasing the shutter, he knows he has captured a really great image.

I ask what advice he would offer to any young, aspiring photographer. Without hesitation, he replies “Stay with your own style. It is better to take a bad photograph in your own style than a good photograph in someone else’s style.” And with this pearl of wisdom delivered, he sits back and sips his tea, calmly.