I am due to meet Susan Gunn at the opening of her new exhibition at Mandells gallery in Norwich. I look around. The canvases are stylish. The whole show is calming. The press dossier tells me that Susan was born into a Bolton mining family in 1965 and that she gained an Art Degree at Norwich. It details countless exhibitions, commissions and prizes including, in 2006, the Sovereign European Painting Prize.

Friends and admirers arrive. Journalists vie for Susan’s attention. She has that rare quality of being able to soak up admiration whilst making it all feel like friendship. Fortunately for me, she is generous with her time. I tell her that Talking Beautiful Stuff is about the narrative behind beautiful stuff that creative people do. She allows me to dig a bit. Her own narrative of the journey from Bolton to Mandell’s is recounted with lucidity and modesty. It is an eye-watering story of talent and success winning over loss and sadness.

A “special gift for art” was noticed by a school teacher. She went on to, and soon dropped out of, Bolton Art School. She set up a successful wedding dress company. She fell in love. She moved to Norwich. She married. She became a student again. She became a mother. She lost her daughter. She suffered an immense grief. She managed to pick up both herself and her family life. She then returned to painting.

Her most recent accomplishment is a commissioned 20 metre work for the Enterprise Centre at the University of East Anglia (“one of the greenest and most sustainable buildings in Europe.”) “Terra Memoria I S,” a smaller version, is part of this exhibition.

I ask Susan what three words apply best to her work. “Earth, infinity..” she reflects for a few seconds “.. and death.” She talks about how her father couldn’t remove all the coal dust from under his fingernails, the near-spirituality of whiteness, her ritual polishing of a certain grave stone and how, with her work, she aims to forge a link between age-old techniques, things primitive, nature and contemporary painting. Everything is rational. There is no artspeak.

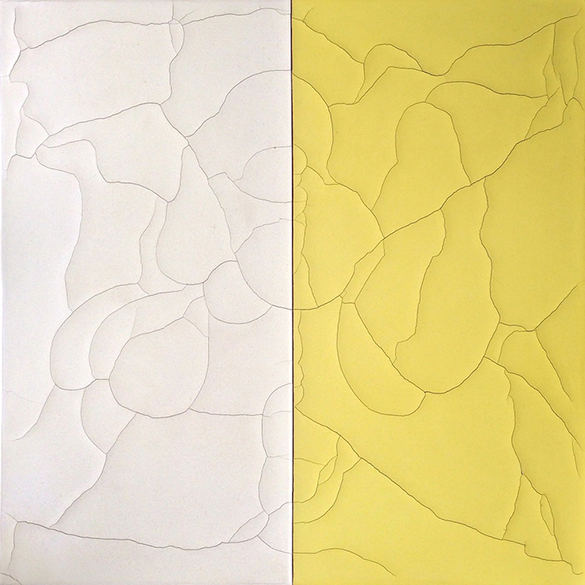

All her paintings carry a visual theme of natural colours with polished surfaces riven with cracks. The appeal is immediate; some fundamental matter is fractured but nevertheless holds together. There is a promise of recreation; of good things. The contrast between the clean crisp lines, the colours and the organic, complex forms is mesmerising. I am drawn into a kind of imaginary space where Susan insists that I stop and reflect on the cracking paint of a lovely old shed or sun-dried riverside mud. My imagination advances; the cracked paint and the fissured mud are cleanly cut into precise rectangles on her studio floor.

“Divide Ground: Orchid Yellows,” Natural pigments, wax and gesso on canvas 70 cm x 70 cm (approx) 2013

I ask Susan about her influences. Top of the list is Alberto Burri who executed a number of “cracked” paintings in the 1970s. The process that Susan has mastered involves age-old materials and techniques. She employs a traditional gesso made of chalk and an authentic glue binder. Its propensity to crack is usually regarded as an undesired flaw. However, she remembers the thrill when she first noticed the complex beauty of fissures appearing in her paint. This was her moment. This was a recall of past, earthy and heartfelt things. Since, she has learnt how the apparent randomness of the cracks in her gesso can, to an extent, be pre-determined by the tension in the canvas, the amount of water in the mix and the ambient room temperature. The natural pigments include coal dust (unsurprisingly,) cochineal, lapis lazuli and suffolk linseed. The final stage involves grinding and waxing the surface by hand.

As we talk, I look around at her paintings. The highs and lows of her life, the evolution of her process and the aesthetic outcome of that process are three intertwined and interdependent strands of one uplifting narrative; one strand can only be appreciated in the light of the other two. Inevitably, I become another admirer of Susan Gunn and her work. Meeting her is a rare privilege.

Thank you both for these insights