I see Alyaa Kamel’s drawings and paintings on Facebook. The on-line human images are, paradoxically, intensely personal. There are new ones every day. Sometimes, they take the form of a reflective and mesmerising little girl; sometimes, they are contorted, shrouded or bound homonculi. Who are Alyaa Kamel’s people? Where do they come from? The more I see, the more questions I have.

On entering her studio in Geneva’s old town, I am surrounded by canvases bearing a variety of striking human figures and faces. Books on every subject imaginable are stacked around the walls. Alyaa smiles, offers me tea and then puts a bulging folder of exquisite sketches in front of me.

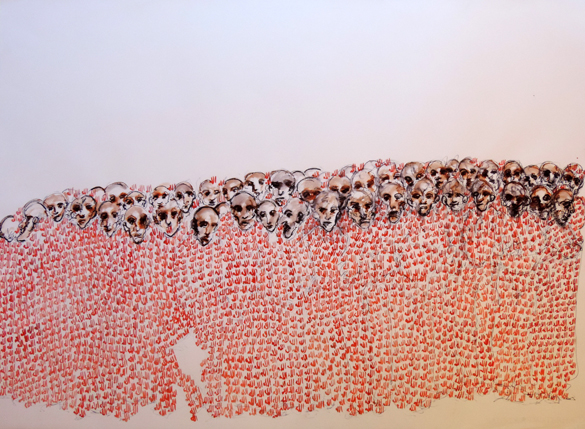

Alyaa Kamel’s work is much more than slick representation of the human form. Her people emanate vulnerability. They display an agitated vitality. They are all taken up with the same struggle. They are aligned in a cohesive force. When I ask about their provenance, Alyaa’s answers contain words like “humanity,” “searching,” “hope” and “freedom.” After some time, I realise that her people communicate her general anxiety for us all: for homo sapiens. And I learn that Alyaa’s people came over the wide horizon of her imagination only two years ago.

In the 1990s, Alyaa studied in London and Geneva. Her subjects included psychology, fashion design and fine arts. She had jobs in public relations and interior decorating. She returned to her native Egypt for a few months in 1998 and, without any great intention to do so, took up painting. Back in Geneva and lacking studio space, she worked on abstract pictures the size of playing cards. She has sold them all and to my disappointment, she never thought to take photographs. She continued to work in the domain of the abstract but on large canvases. What she exhibits she sells.

A return visit to Egypt in 2011 to show her work coincided with the beginning of the “Arab Spring.” Something about the people’s struggle against oppression re-aligned the beacons that guide her creative journey. Alyaa Kamel’s people were born. She emphasises they are not Egyptian nor even Arab. They are not women, men or children. They are simply people. The first time they were seen in Geneva was at the Tafkaj gallery in 2012: it resulted in another sell-out.

Alyaa’s people are homogeneous but at the same time, they appear as individulas. To acieve this effect is no mean feat. The fluid lines with which Alyaa depicts her people show a profound sense of anatomy. The effect recalls her interest in fashion design. The faces are, you would easily believe, the faces of real crowded people. They are hungry, anxious but nevertheless united.

Alyaa shows me her what I consider her most powerful work. A crowd of bare-headed men is enveloped by one Arabic word red-written hundreds of times – “Allah.” The faces have a haunting skull-like air. Is this a warning to us all that religion offers no better – nor a less bloody – alternative to repressive government? Alyaa insists her work does not carry a political message. It is, rather, an expression of both hope and concern triggered by the events that moved her in Cairo two years ago.

After an hour or so, I have not really deciphered the “Why?” of Alyaa Kamel’s people. I am not sure Alyaa herself has clear answers. For me, her people and their narrative combine to remind us that human destiny is largely out of our hands and increasingly uncertain. And if I’ve got this wrong, my admiration for Alyaa’s work remains unchanged.