Geneva, 25 December, 2020

Yes, it’s come to this…. Home-made Christmas cards! My golfing friends may – or may not – appreciate my little contribution to seasonal cheer. But then, I guess right now, we need all the cheer we can get.

It was Christmas day of 1981; not long after beginning my first job after qualifying as a doctor. I was on-call for the surgical wards at Addenbrookes Hospital in Cambridge. The staff nurse called me to say that one of our patients recovering from surgery – let’s call her Maisie – had an irregular heart beat. I went up to see her; her bed was empty. Maisie, a good old Fenland character, was clearly not bothered. I found her in the TV room glued to the BBC’s newest production of the nativity. “Hello, Maisie” I said, “Nurse wants me to check your heart beat. I’ll just do a test. Is that all right?” Maisie kept her eyes on the screen. “Whatever you say, doctor! But coz I can’t go to church like what I usually do, I want to watch the nativity.” I untangled the wires of the ward’s electrocardiogram, applied the pads to Maisie’s wrists and ankles and switched the machine on. I glanced at the TV; a tired and obviously pregnant Mary rode a donkey; Joseph walked alongside. “Are you enjoying the nativity there, Maisie?” I asked. “Oooh, it’s lovely!” she replied. The electrical impulses of her heart beat appeared regular and normal on the small screen; obviously, any irregular beats had been transient. Nevertheless, I thought I would let the ECG run for a minute or so. “Who’s that?” Maisie asked pointing a gnarled finger at the screen. “That’s Mary and her betrothed, Joseph. And it looks like Mary’s pregnant, Maisie!” We both chuckled. “And she was a virgin!” I added. For the first time, she looked up at me. A question was clearly forming in her mind. “Good catholic girl was she?” She cackled. “Well, I’m not sure they had catholics in those days!” I said. “When was this then?” Maisie asked. I wasn’t sure whether she was pulling my leg. “Well, Jesus was born one thousand, nine hundred and eighty-one years ago, Maisie.” Her eyebrows raised. “Oooh! And, what…. on Christmas day?” Her heart beat remained steady and regular. “Poor Jesus. I’d hate that!” she continued. “I got a nephew who was born on Christmas day and he only gets one lotta presents each year coz everyone does his Christmas present and birthday present together. Thats’s real cheap, I say!” Maisie, it seemed, was not pulling my leg. After scenes of shepherds and kings truckin’ along, the viewer was taken through a jolly busy way-side inn and into a stable. Mary was lying in some straw and well into her labour. A close-up of Joseph’s face revealed no little agitation. “Oooh! The anxious father!” exclaimed Maisie. I said nothing. Soon, Mary was crying out in pain clearly about to deliver. Maisie’s mouth hung open. Her heart rate, whilst still regular, had now picked up somewhat. Turning to me with eye’s wide in wonder, she asked “Do you think it’ll be a little boy or a little girl?”

Few young docs end up where they thought they would. In 1981, I was wondering if I had what it takes to become a consultant vascular surgeon. I went on to get a surgical qualification but abandoned ship (the UK’s National Health Service) to work for a number of years as a field surgeon for the International Committee of the Red Cross. I then became the medical adviser to the ICRC on issues relating to violence and weapons; a role in which I inevitably found myself in the domain of international mechanisms preventing the development, production and use of chemical and biological weapons. In the mid-1990s, I had the good fortune to meet a charming and brilliant American scientist by the name of Matt Meselson. (Matt together with Franklin Stahl performed what has been described as the “most beautiful experiment in biology.” After the double-helix structure of DNA had been proposed by Watson and Crick in 1953 , Meselson and Stahl, in 1958, established how DNA replicated itself.)

Matt dedicated a large part of his professional life to the scientific aspects of preventing the use of chemical and biological weapons and did probably more than anyone to promote within the scientific community the importance of the 1972 Biological Weapons Convention. He and I often engaged in discussions about the worrisome spectre of a whole new generation of microbes and toxins both natural and man-made. He was far-sighted. Finding ourselves in a workshop here in Geneva, we shook hands warmly. He said, “You know, Robin, we’ll see the day when we don’t shake hands anymore. We’ll be bumping elbows. It’s inevitable.” We’ve bumped elbows since. I am sure Matt would have wise counsel for the team investigating the origin of the virus responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic.

Us Brits have a quaint but important tradition at Christmas dinner: cracker jokes. These are written on little pieces of paper that fly out of the exploding Christmas cracker. The jokes are so bad that, when read out, they predictably generate a disappointed groan from everyone sitting around the turkey-laden table. The idea is that squabbling families stop squabbling for just a couple of minutes because they are all unconsciously united against the unknown author of the awful cracker joke. As PG Wodehouse would say, it’s about the psychology of the thing. So… Covid Cracker jokes…….. The year 2020 has been awful. It’ll end in tiers! (UK only!) .. or .. What does the Trump family do for Christmas dinner? They put on a superspread!

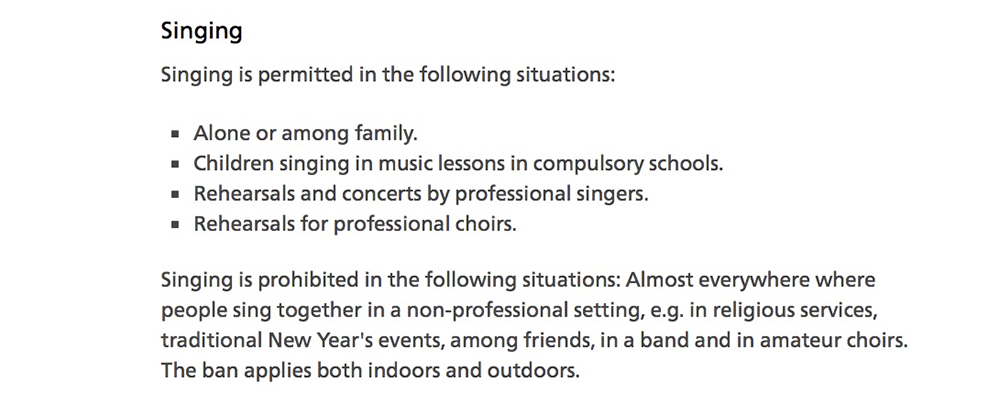

Merry Christmas everybody! But if you’re in Switzerland, no singing!

Gotta love the Swiss! The above is from the government’s Covid info site.

See y’all in 2021.