Geneva, Wednesday 1 April 2020

Let’s stay with the nurses; not only because nurses are fab but also because I see that all the COVID-19 dedicated hospitals being constructed in the UK as I write are to be named the “Nightingale Hospitals.” And so they should! Florence Nightingale was quite some gal! If ever there was someone who made a difference to the plight of sick people in big numbers, it was her.

Florence Nightingale found herself with fifteen other nurses attached to the British Army fighting the Crimean war in the mid-1850s. She was appalled by the plight of the wounded and sick soldiers. Nothing was done for them. More were dying from preventable infections than from wounds because of the appalling insanitary conditions of the make-shift hospitals. Giving consideration to the wounded and sick of their armies was something governments of the day simply didn’t do. She let her displeasure be known back in London via a letter to the Times which, of course, was not welcome across the board, but hit hard.

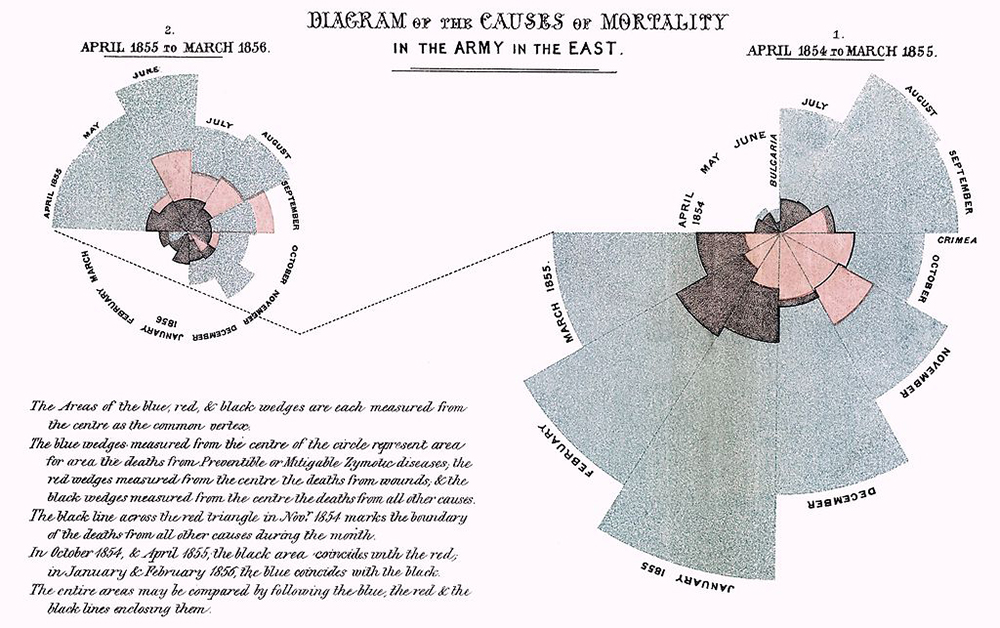

She was probably the first person in health care who recognised the principle: if you want to manage it, measure it. She also pioneered data visualisation. Take a look at this graph she made from data gathered in the Crimea. She presented this and similar graphs to the British parliament as evidence of the impressive impact achievable on seasonal mortality due to infectious disease if basic measures of hospital hygiene were implemented. (She even made dumb-downed versions for the MPs who were unused to looking at graphs.) Her data-based insights paved the way for sanitary reform at home and abroad. She designed better hospitals; every British nurse will have worked on a “Nightingale” ward. She insisted on a formal and universal classification of disease. She was the first woman member of the Royal Statistical Society. Even though she wrote that she had been called to her work by God, she established the first ever secular nursing school at St Thomas’ Hospital in London; a major step in the professionalisation of nursing. She never married and, inevitably, became an icon of Victorian culture.

Less well known – and, arguably, as influential – was a letter written by Miss Nightingale in 1861 to a Swiss gentleman by the name of Henry Dunant. Young Dunant had been on a business trip to Northern Italy in1859 when he came across a village called Castilinagno the church of which was full to overflowing with the wounded from a battle just up the road at Solferino. He did what he could do by calling in as many people as possible to help. He realised that from whichever side of the conflict the wounded came, they were no longer enemies. “Tutti fratelli!” was the call of the day. (We’re all brothers!) Deeply moved by this experience, he hurried back to Switzerland and wrote his visionary “A Memory of Solferino.” It’s difficult to believe now, but the European aristocracy of the time saw war as something noble and generally fun. They hadn’t yet realised the impact on soldiers of increasingly effective firearms. Dunant’s publication in which he gave a vivid and moving description of his experience caused wide spread concern in elevated societies. He made four proposals. The first three were: that the wounded should be spared further attack; that the wounded should be protected by a universally recognised flag (later accepted as a colour reversal of the Swiss flag i.e., a red cross on a white background;) and that a neutral, international commission would take care of the wounded whenever there was a battle. The fourth proposal was that the first three would be agreed upon in a binding treaty between all nations. The commission would become the International Committee of the Red Cross and the treaty would become the First Geneva Convention of 1864. Great stuff!

And so far, so good. But Dunant hadn’t factored in Florence Nightingale. And didn’t she have something to say? She let her displeasure be known again. Three of these four proposals were fine but she got quite exercised over the idea of a neutral body caring for the wounded. Bruised by her own experience, she pointed out that this would simply relieve governments of their responsibility for their own wounded soldiers. She was on it like a bonnet! This is the reason why the medical services of all military forces now carry the red cross (or red crescent in muslim countries.) As a result, not only are the wounded and sick protected from attack but also military health-care personnel and facilities likewise. This change was incorporated into the Geneva Convention. It is difficult to think of anyone who has had more influence on our lives and well-being than our Florrie.

It must have been 1991. Kabul under heavy bombardment. I was asked if I could spare a minute between operations to speak to a journalist. Well…. perhaps it was important to let the world know what was happening here. I gave him a run down about what we were seeing (just so many wounded people) and what we were doing (barely functioning as a surgical hospital.) I asked him if he would like to speak with one of our nurses. He replied “Why do I need to do that? I’ve spoken to the surgeon!”

Busy day in lockdown. No putting. Watch this space.

Great summary Robin. From Wellington after 1 week in lockdown. Am happy that NZ have upped numbers being tested…still not at the Swiss level however. I received my proof of life form today from Caisse suisse, bureaucracy doesn’t stop….have 3 months minus the 2 weeks the letter took to get here to have it signed off. Here’s hoping we are out of level 4 by then…. x to you and Liz