Geneva, Saturday 28 March 2020

I can’t help wondering what my father would have made of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although he practiced medicine in a different era, I’m sure he would have had wise words for the thousands of health-care workers who are doing their level best under the most trying of circumstances.

My father was 27 years old when he moved with his wife and son (my older brother, Garth) to rural Norfolk in 1953. His single-handed general practice was based at home where he had a consulting room and a dispensary. His practice was, to a large extent, self contained. He was permanantly on-call for his patients. He made up to twelve home visits per day. Emergencies were rarely sent to the Norfolk and Norwich Hospital an hour’s drive away. It was the early days of free health care under the then new National Health Service. Patients had few expectations beyond the care and attention of their doctor and that he “did his best.” Doing his best was often repaid with a chicken or a box of apples.

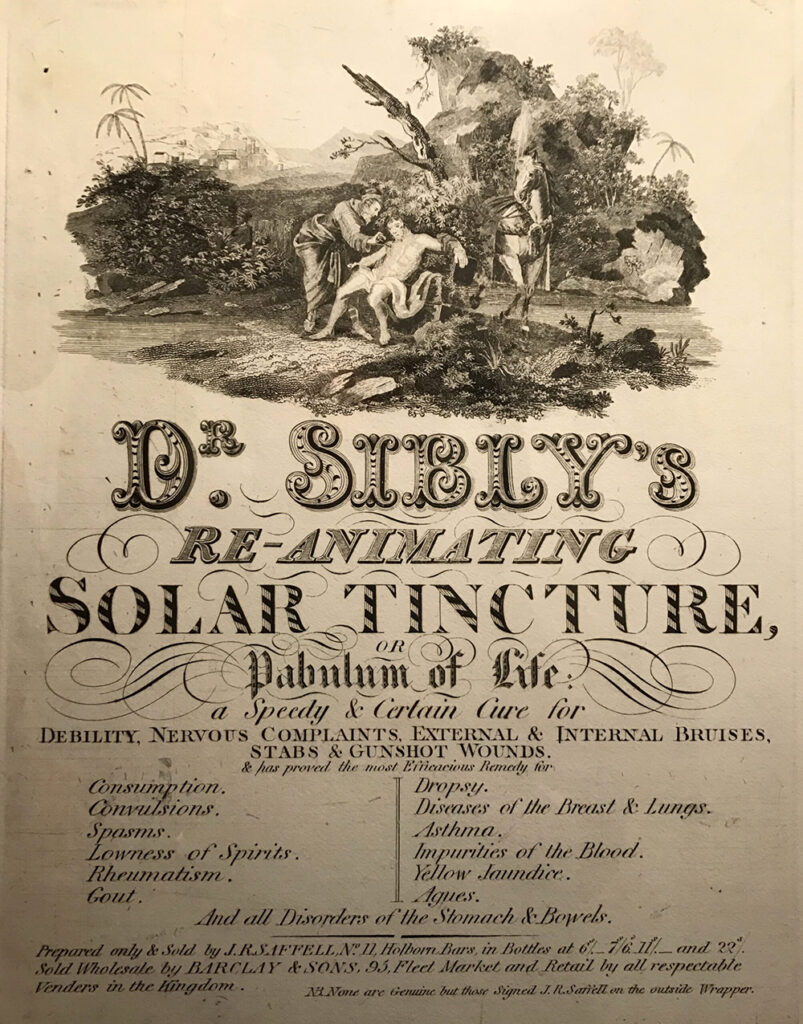

He had this poster from the early 19th century in this consulting room. I think it was to remind him and his patients just how much medicine had moved on. It also served as a warning about quacks selling potions. As a former trauma surgeon, I can’t help being amused by the claim that Dr Sibly’s solar tincture was a “speedy and certain cure for stabs and gunshot wounds.” But the problem is, people have always believed in magic potions. They still do and are exploited as a result.

In the mid 1950s, my father was the first doctor in the area to give the new oral penicillin outside a hospital setting. He told me on one winter morning in 1956, he had a message from a man who barely made a living by cutting reeds for thatch far out on the marshes. One of this fellow’s young twins had a high fever and ear ache. My father knew the family. Both parents were illiterate.

To reach their house, he had to take his old motorbike along the edge of the railway line that connects Norwich to Great Yarmouth. It was snowing. He was welcomed in by the concerned mother to the most basic of homes. There was little warmth. The two twins, a boy and a girl, about seven years old were huddled together on a filthy sofa. The girl was sweating and clearly out of sorts. On looking in her ear, the obvious diagnosis was otitis media, a very common childhood condition at the time that could have serious consequences including brain abscess and permananent deafness.

My father explained his findings and that he had brought with him a new wonder medicine called penicillin that was most effective against precisely this kind of infection. He explained that the syrup had to be taken four times a day and the child might have difficulty swallowing it because of its unpleasant taste. Convinced the mother understood, he said he would return in 48 hours.

Following his tracks in the snow from his previous visit, my father returned to the house two days later. The girl twin had no fever and seemed to have made a miraculous recovery. He asked if it had been difficult to swallow the new medicine. The mother replied that her daughter had no difficulty at all taking the medicine because she, the mother, had given it to the boy. She claimed any time the girl was sick, the boy happily took the medicine and this always made the girl better!

Today, in the face of the greatest global health emergency ever, my father would have warned us of those who take advantage of the poor and the uneducated by blurring the distinction between magic and medicine. Modern medical practice is steeped in ethics as it should be. It protects patients even if they believe in magic. I spent some years working as a surgeon for the International Committee of the Red Cross in conflict zones and under-developed countries. The most valuable thing I learnt about big health emergencies is that the greater the crisis, the more susceptible people are to exploitation by the Dr Sibly’s of the world and the more important it is for health-care workers to adhere rigidly to the tenets of medical ethics. It’s all about the patient being sure he or she can trust the doctor or the nurse to act in their best interests.

My father had one most demanding patient; a well-to-do but unhappy lady in her sixties. Her only source of joy was her little dog that she deemed so handsome that she wanted to enter him into a show. She asked my father if he had advice about lightening the dark line down the little chap’s back; a feature she was sure would lose points. My father suggested seeing Mr Jones, the village chemist; he’d certainly have a suitable product. Now Mr Jones was a good old Norfolk boy and it so happened that, a day or two later, my father was chatting to him when he saw the lady in question about to come into the chemist’s shop. My father hid behind a shelf of cough remedies. He heard the lady ask Mr Jones if he had something to lighten the colour of dark brown hair. He produced a bottle for her inspection. “Now, Mr Jones” she asked in an ernest tone “Do you think this will be OK on my chihuahua?” Mr Jones scratched his head and said “I reckon so, Madam. But I’d advise you not to ride a bicycle for a few days!”

Today’s putting competition got delayed through house work and phone calls. We started late. Wait for this…. We had to abandon the game on the second play-off hole because of poor light. And neither of us had missed one of our twenty putts!!