It’s the Rugby World Cup. The New Zealand All Blacks are looking to lift the trophy for a third successive time. And don’t we all love their haka?

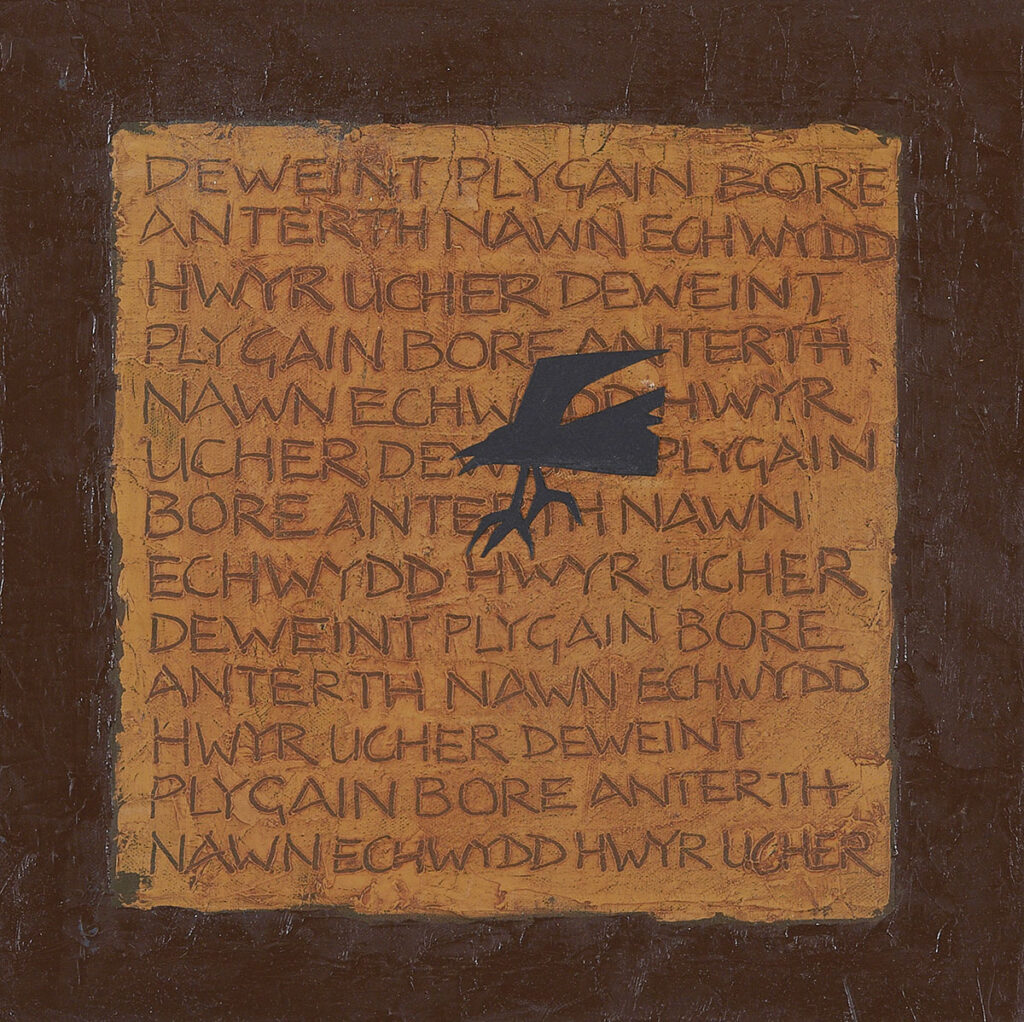

There are numerous hakas which have been passed from long-ago Maori culture. Many were war dances. The haka most frequently performed by the All Blacks is the Ka Mate. It was composed in 1880 by Te Rauparaha, war leader of the Ngāti Toa tribe in New Zealand’s North Island. Translated, the main body of the chant is:

I die! I die! I live! I live! I die! I die! I live! I live! This is the hairy man who fetched the sun and caused it to shine again. One upward step! Another upward step! An upward step, another… the sun shines!

The use by the All Blacks of the more aggressive Kapa O Pango haka was put on hold in 2006 because it included what was perceived as a throat–slitting gesture. However, it was resurrected controversially for the big match against Australia earlier this year.

Whilst best known in the context of rugby, these group dances are also performed on other important occasions such as funerals and welcome ceremonies. Many include women but the famous tongue-protruding aggressive hakas are only performed by men.

The connection of the haka to rugby dates back to 1888 when an all-Maori team toured Great Britain and before kick-off rather startled the Surrey county team. The Ka Mate haka was first performed in 1905 by the “Original All Blacks” prior to a match against Scotland. Help ma sporran!

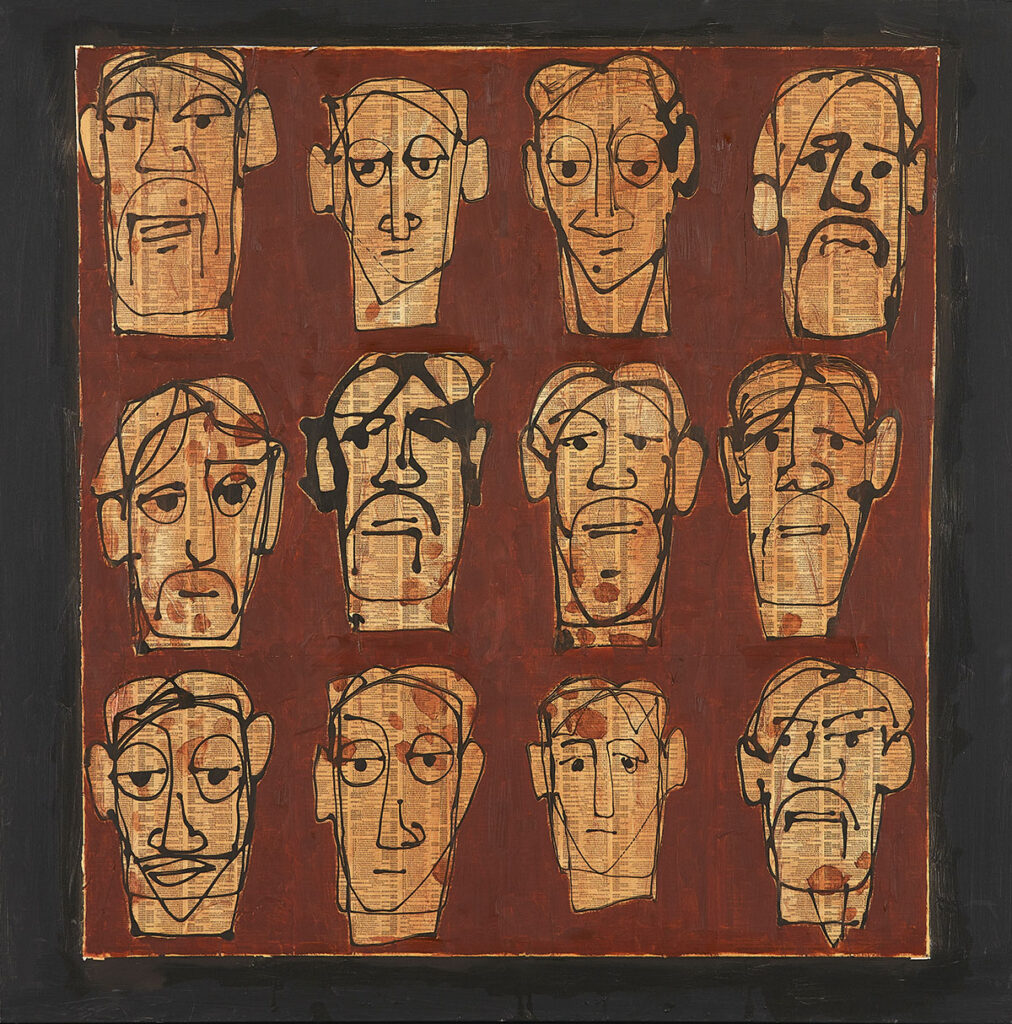

The whole of an All Black team in haka-mode is so much more than the sum of its fifteen parts. As a ritual for scaring the living daylights out of the opposition and boosting one’s own morale, the haka is very effective. There is a debate in international rugby circles about how an opposing team might best counter the haka. Most adversaries choose to stand shoulder-to-shoulder in a bid to stare down the New Zealanders. The idea is to pass the message that we really are not intimidated, really… not one tiny bit. This passive choice involves looking like, in comparative terms, a line of vegan train-spotters. The other option is just to ignore it all and carry on warming up; just jogging around the pitch passing and kicking balls. But this apparent disrespect risks further inflaming that All Black passion. Dilemma! Whatever, the haka is there. It is centre stage in everyone’s mind. Neither opposing players, match officials, the crowd nor the millions of tele-viewers can ignore it. It’s as good as a seven-point lead at kick-off. And the truth is that every spectator loves the spectacle independent of allegiance. Personally, I think that the England team when next facing the All Blacks’ haka should dig deep into Anglo-Saxon culture and do a spot of pre-match Morris dancing!

Rugby has a near-religious place in today’s New Zealand. Whilst the haka was put on the world stage by the All Blacks, the ritual now goes way beyond rugby and bores deep into the psych of all New Zealanders. There is no politically correct tokenism here. I ask friends of different nationalities what words they associate with the haka. Answers include “powerful,” “intimidating,” “ferocious,” “awe-inspiring,” “up-lifting” and, most tellingly, “patriotic.” If you want to see just how the haka creates a point of unity between the European and Maori cultures of New Zealand, take a look at this school haka. Add “eye-watering.”