If you visit only one exhibition this year, make sure it’s Big Bang Data at London’s Somerset House. Believe me! You have to go! I struggle to find the words to describe it. I get half-way there with “brilliant,” “admirable,” “vitally informative,” “challenging,” “jaw-dropping,” and “mind-boggling.”

The central theme is “big data.” It really is BIG! (Or should I say, they really are BIG?) The digital data universe is massive, globally connected and expanding exponentially. The ingenious and interactive displays of this beautiful exhibition focus on the technology and implications of what will prove to be one of the most important developments of the twenty-first century. The exhibition demonstrates how corporations, authorities and hackers can collect and analyse data about the environment, businesses and particularly us. It is at once wonderful and concerning. Big data has arrived uninvited and unannounced but is here to stay. It is already transforming our society, culture, security and politics. It is the human future as was electricity, air travel and television.

Telegeography, “Submarine Cable Map” 2015

A floor map shows the undersea cables that connect thousands of vast, impeccable and impersonal data storage banks. The cables and databanks are each the property of different corporations. Voila! “The Cloud!” (As the exhibitors point out, this is a misleading term. A cloud in the sky cannot be divided up according to different owners. Except for satelites, most of the physical infrastructure of The Cloud is on the ground or under water. There is no clear blue sky on the other side!)

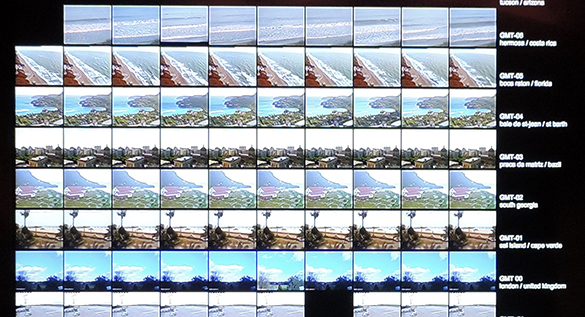

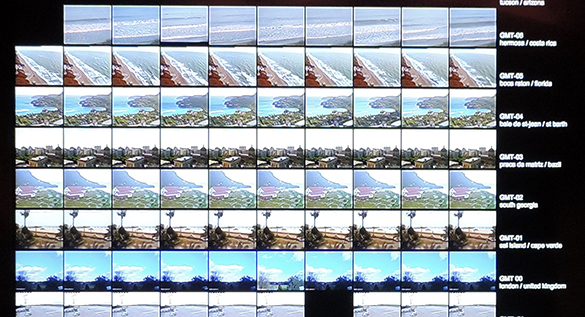

Thompson and Craighead, “Horizon” Digital collage from on-line sources 2015

An elegant and benign manifestation of the possible is given by Thompson and Craighead’s “Horizon.” This displays a narrative clock made from real-time, constantly updated images from webcams around the world.

Rafael Lozano Hemmer, “Zero Noon” Software 2013

Rafael Lozano Hemmer’s “Zero Noon” is an unconventional digital clock fuelled by internet-refreshed statistics. It tells the time based on metrics such as hamburgers sold in Detroit or the number of animal species becoming extinct per day. At midday, the clock is reset to zero with display of a new statistic. At 14.30, it tells me that prostitution in the UK has turned over the equivalent of US$64,210 in the previous two and a half hours.

Among the 51 other displays, “Unaffordable Country” by the Guardian Newspaper is an interactive data visualisation that exposes the UK’s dire housing crisis. On entering their salary and postcode, around 96% of participants find that there is no affordable property in their vicinity. Paolo Cirio and Alessandro Ludovico use “Face to Facebook” to show how they stole a million personal profiles on Facebook to create characters on a false dating website, Lovely-Faces.com, classifying them by their facial features. With “Stranger Visions,” Heather Dewey-Hagborg has 3D printed human faces based on DNA that she obtained from objects such as chewing gum and cigarette butts collected in public places.

What I learn is that the volume of data generated by our everyday lives is booming in lockstep with the capacity to analyse it. Those who are in a position to harvest and use this data are in an increasingly powerful position to influence us individually and collectively. A fundamental physical tenet is that power without control can only be dangerous. Does it apply here? Do we have the wisdom to harness the power of big data responsibly?

EasyJet, Safety On Board, Laminated plastic card

I am on an EasyJet flight out of London and can’t help reflecting on what big data will mean for future generations. Next to me is a little girl of about three years. What will she make of it all as an adult? Unwittingly she tells me. From the seat pocket in front of her, she picks out the laminated Safety On Board card. She looks carefully at the shiny surface and stabs her little index finger into the icons assuming that the card will come to life and reveal something more interesting. She tries again. “Not working!” she cries out to her mother. I realise that big data will be a part of her life and that she will be no more concerned about it than I am concerned about electricity, air travel and television. I wish her well.