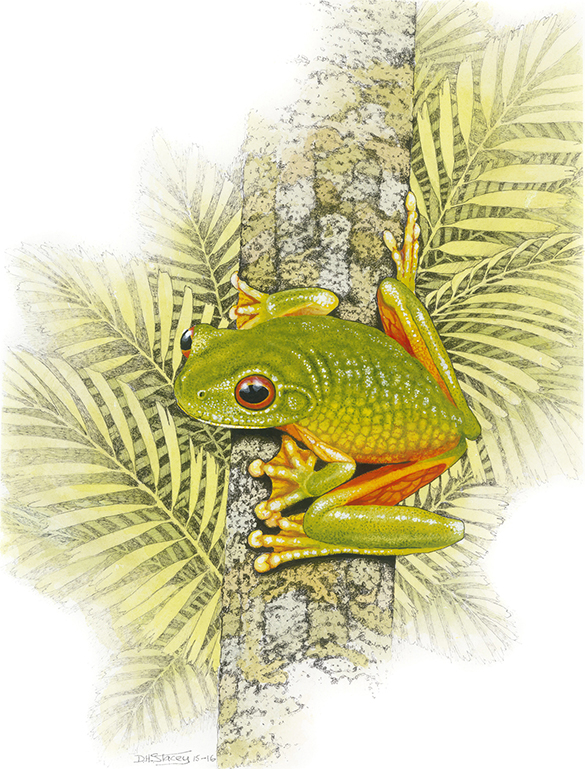

Scientific latin flows easily as painter David Stacey and I talk about frogs in his gallery-studio in Kuranda, Tropical North Queensland, Australia.

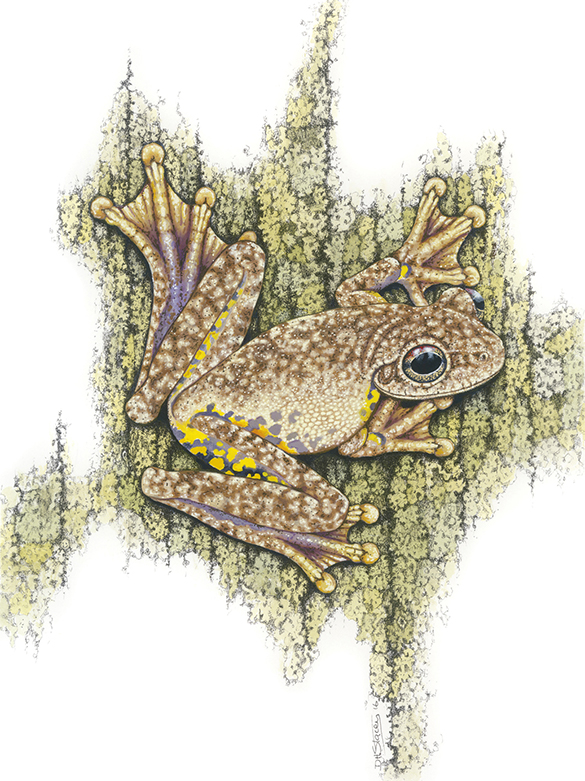

Turning from the subject of Litoria xanthomera breeding in chlorinated swimming pools we move to view his painting of Litoria rothii. This fabulous rendering of a Northern Laughing Tree Frog clinging to a lichen covered tree with its sucker-like toe pads is simply exquisite. The identification points and character, or ‘jiz’, of this species, one that I know well and have painted myself, is captured to perfection. The fine, warty detail, camouflaging patterns and striking yellow and black ‘flash markings’ are, to me, deliciously amphibian. I want to touch it. I notice other frogs in the original works, reproductions and greetings cards around me. They all have the same effect on me.

I have written about David Stacey before. His work reveals a man deeply connected to his subjects; namely, the environments, ecologies and species of the world’s most ancient rainforests which are found only in this part of Australia. This connection seems to lead naturally, in his words, towards ‘obsession’. The sheer volume of his output since our last meeting does indeed testify to an obsession.

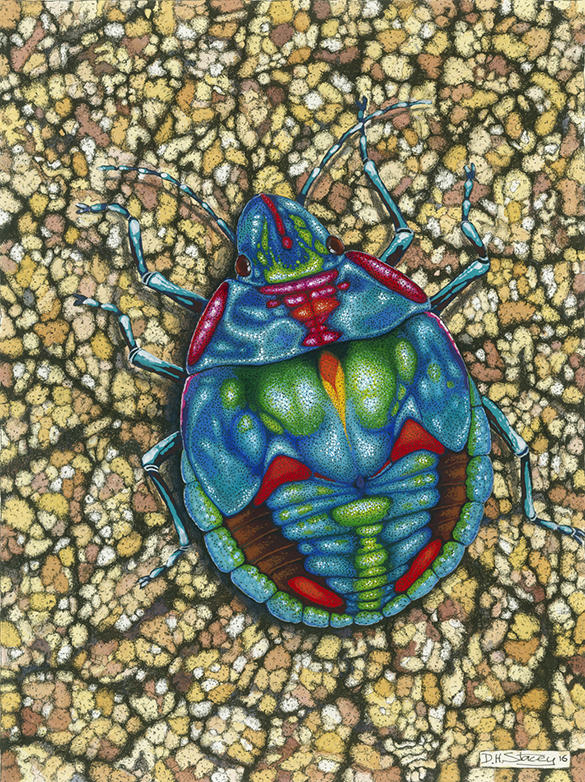

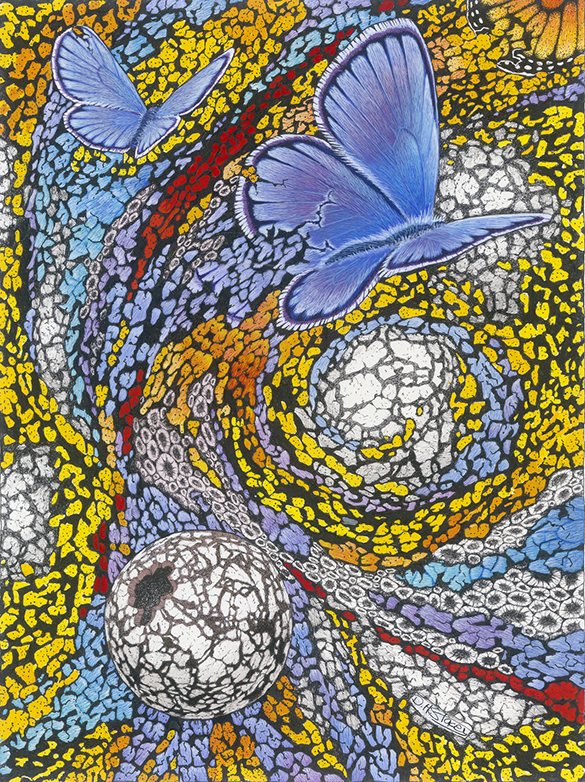

David is generous with his time. We talked about technique and style, composition and reference material. His style is unique; a ‘Stacey’ would be recognised anywhere. His latest major exhibition, featuring 70 paintings, was held at Brisbane’s prestigious Redhill Gallery during November 2016. The exhibition consisted mainly of his fine, pen and ink drawings which he then “colours in” with wonderfully opaque acrylic washes overlaid, where necessary, with thicker acrylic application. (All the works shown in this post are from the exhibition). We also discussed problems that being ‘artistic’ can bring!

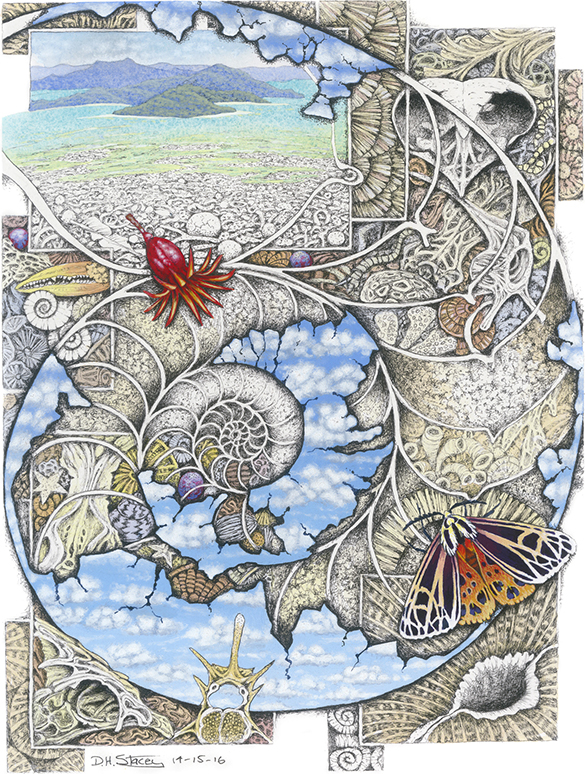

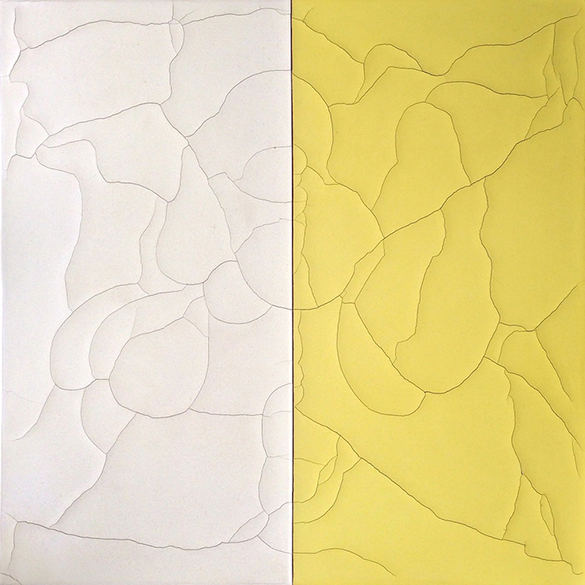

However, it is David’s sense of composition that particularly impresses me. How he thinks his trademark compositions through to completion is a marvel. He balances colour, tone, form and space. He leads the eye; sometimes by not colouring or leaving something out. It is as if he considers your peripheral vision as well as your focus when composing. Clever! Some of his paintings leave me imagining what might be there that he has left out. This is the same feeling I get in the rainforest where so much is hidden in the green, luxuriant half-light.

This compositional prowess effectively renders each painting far more than just a portrait of a species. (My own paintings, however hard I try, always end up being just that). David’s works stand alone as accomplished creations, pleasing to the eye, where the subject matter of the painting becomes simply one element among many that make up the whole.

David has another ‘style’ which is extraordinary. He describes it as ‘surrealist’. It is these works that hold me in fascination as I explore them. They are conglomerations of images: landscapes, creatures and plants, abstract patterns and even maps. They are dream-like, thematic and thought-provoking and are woven together with his accomplished, compositional artistry.

Our conversation was far more than just an interview for this post. I learned stuff! I also identified our shared obsessive need to portray the natural history that fills our minds with interest, respect and appreciation. We have in common those lonesome journeys and vigils in the wild places where we observe and photograph reference material and add to our knowledge and understanding of the wild. We talked of the difficulties of being obsessional ‘artists’ and how our work is profoundly personal being often difficult to market. At times, we have both ‘prostituted’ ourselves to create for a commercial market driven by conventions, expectations and desires of others. More than once David used the expression “money is corrupting”.

These days in Kuranda are my last in Australia. I am about to migrate back to Britain after four years of trying, unsuccessfully, to assimilate into life here. But David Stacey is where he should be. As a man so connected to the rainforests of his home he clearly understood my similar connection to the natural history of Britain and Europe. We spoke of the recognised phenomenon where an Aborigine may die if removed from his ‘country.’ In this extraordinary painter-naturalist, I found a kindred spirit who understood and acknowledged my expression, ‘homesickness is a gentle term for grief’.