The main staircase of the Royal Scottish Academy has a new carpet. I’m smitten the moment I walk in.

‘Wool runner’ comprises dozens of fleeces bearing the farmers’ colour coding that signify the owner of the sheep or which ewes have borne twins. The fleeces are attached to netting by thorns. It is simple in concept and stunning in effect. I stop and gape. I have the feeling that the fleeces are running up the stairs close-knit(!) and enjoying their new freedom. Andy Goldsworthy could offer no better welcome to an exhibition celebrating fifty years of his astonishing work.

At the top of the stars, I encounter ‘Fence’. Two doric columns are joined by multiple tense strands of barbed wire all reclaimed from farms. It jives with the fleeces and serves to emphasise Goldsworthy’s work on the land, obstacles encountered and boundaries pushed.

‘Wool runner’ and ‘Fence’ are just two of a number of site-specific works. The two chambers flanking the stairwell are each dedicated to installations that defy my photographic abilities. ‘Skylight’ depends on the light from a hexagonal skylight from which hundreds of stalks of reed mace (bullrushes) are hung giving an otherworldly beam-me-up feel. With ‘Gravestones’, Goldsworthy has covered the floor with rocks that were dug out of the ground and abandoned by the grave-diggers of 108 different Dumfrieshire graveyards. The work emanates the passage of time, abandon and sadness.

My first impression of ‘Oak’ is a floor covered by leafless branches. Viewed from one end of the room, though, I find that hundreds of similarly sized branches have been laid out in a gorgeous and angular symmetry that draws my eye and invites me to walk toward an intriguing and balanced serpentine work on the far wall.

I can’t help it. I walk in close and examine how Goldsworthy has made ‘Fern Drawing.’ I’m in awe. Just how much time has he spent on this? Further, will it outlive this exhibition?

A whole room is dedicated to ‘Flags’. There are fifty. They have different hues of an earthy colour that hum to the theme tune of this exhibition. I have to turn to the exhibition guide for the backstory. ‘Flags’ is a commissioned work for the Rockefeller Center in New York. Each flag is dyed with the reddest earth that Goldsworthy could find in each of the states of the USA. He makes reference to the powerful connections us humans make between earth and flags. He hopes that the boundaries and cultural differences currently associated with flags could be transcended and would no longer be a source of division.

As I move through the other rooms, I discover a sumptuous tribute to the decades of imagination, creativity, determination, technical expertise and environmental concerns of one of Britain’s best-known contemporary ‘artists.’ The photographic history presented here focuses on his ephemeral and temporary works. I adore these; their creativity is, intentionally, given by the second law of thermodynamics. Goldsworthy understands entropy; that all things in the universe inevitably move to a more stable state.

I stand in front of a photograph of one of Goldsworthy’s most iconic and exquisite temporary works; it is made from the feathers of a dead heron. I become aware of something I feel whenever I look at Goldsworthy’s work. Something beyond admiration. It creeps up on me. It’s a kind of jealousy that sits somewhere between ‘It’s not fair!’ and ‘I could have done that!’ ‘It’s not fair!’ that one person can have such a wide-ranging imagination. ‘I could have done that!’ is instantly followed by the obvious autoreply: ‘Well, I didn’t, did I!

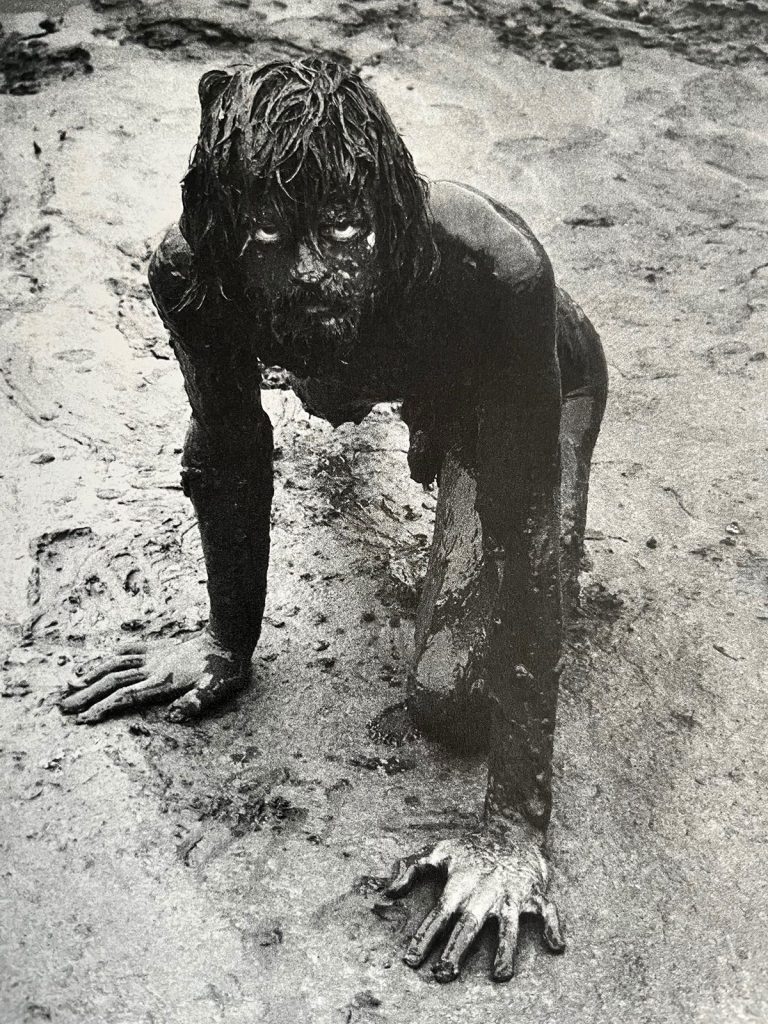

I am not a fan of videos in an exhibition. They tend to the banal and steal minutes of my life. I see a group of ten people transfixed by a screen showing a rocky Maine coast. Sea weed heaves and swirls gently as the tide comes in. I look at the guide. It lasts twenty-nine minutes! Nevertheless, I join the others. One says ‘I don’t believe this!’ Another says ‘He’s gonna die!’ The tension is palpable. And then I get it. Andy Goldsworthy has buried himself in the sea weed. At twenty eight minutes, in soaked tee-shirt and jeans, he emerges only when the rocks and sea weed are entirely covered by sea water. We all clap!

This portrait of the artist as a young man is now more famous than whatever it is he was working on in Morecambe Bay. He just felt he was engaging with the world. By the way, I couldn’t have done that!

Bravo Andy! Top bloke!

Do not miss this exhibition. It ends on 2nd November.