I am in Cambridge (UK). I am expected at Gonville and Caius College for dinner. I have time. I stroll. Nostalgia settles in.

The first thing of great beauty I see is the “Mathematical Bridge” that crosses the River Cam connecting the two parts of Queen’s College. It was designed by William Etheridge, and built by James Essex in 1749. It appears to be an arch but is composed entirely of straight timbers built to an unusually sophisticated engineering design, hence its name. It is so elegant. If some wag tells you that before its rebuilding in 1866 there were neither nuts nor bolts, it is not true: they were just better hidden.

The next thing that catches my eye is a flyer for a lecture that is starting right now as I stroll. Psychologist Steven Pinker from Cambridge (USA) is in town. He is one of the most influential living scientists. His subject is violence. My subject. I would like to go but cannot. I wonder if he cites any of my hard-won data on people in danger. Oh well…. My memory lane crosses the river again.

Next to Clare College bridge, I am pulled up by an exquisite sculpture of Confucius (551-479BC) gifted to the college in 2010 by the sculptor Wu Weishan, President of the Chinese Academy of Sculpture. Wu’s Confucius has already survived four Cambridge (UK) winters. He seems to be enjoying his outdoor séjour in this seat of learning. The sculpture is, at first impression, rough and raw. I run my hands gratifyingly over the chunky silk gown. I examine the face; it emmanates a sense of humour. This Confucius could even be a bit of a rascal; there is something piratical about that smile. At the same time, he seems to be on the point of saying something really profound. But it’s the hands that really draw me in to this work. They are delicate and inwardly turned; a message of sincerity. This is a man who brought notions of morality, governance and justice to large swathes of the world.

I guess that Wu would not have had photos to work with. I would put money on him basing his sculpture on this ancient wood print of Confucius from Wu Daozi (680-740AD).

On to Gonville and Caius.

In “Tree Court” there is a striking statue of the physician William Harvey (1578-1657.) He was quite some guy. He worked out that blood was pumped around the body by the heart. He described this research as “an arduous task.” In 1628, he published a monument of medical science under the title “On the Motion of the Heart and Blood.”

The College’s Gate of Honour is very beautiful in its proportion and detail. It was commissioned by the good Dr Caius himself in 1565. The designer is not known. It is only opened once per year on Graduation Day and I once walked through it giving little thought to the mathematically intriguing six sundials on the hexagonal facets of the tower atop the gate. I am dizzy from this all-about tradition, beauty, knowledge and learning. Then I mount the oak stairs into the dining hall of Gonville and Caius.

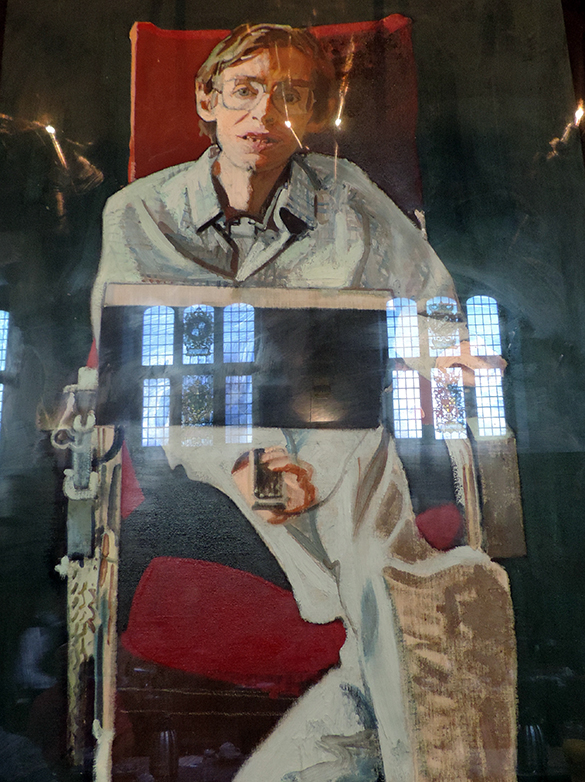

The last rays of the day’s sun filter through the hall’s high windows illuminating a huge portrait of another genius of the College. Stephen Hawking peers down from on high. The painter (unknown) has captured well that famous cheeky-geeky face. Using warm colours, he has cleverly portrayed the contorted body resting comfortably in a high-tech wheel chair. Hawking was the first to set forth a cosmology explained by a union of the general theory of relativity and quantum mechanics. (I stole this last sentence from an authoritative source and – like most people who have it on their bookshelves – did not get far beyond the first page of “A Brief History of Time.”) Unsurprisingly, his work shook his – and his wife’s – religious beliefs.

Cambridge. So much learning. So much knowledge. Such beautiful testament to learning and advances in knowledge. This is stuff that, once discovered and over time, we all come to believe. But somehow, in the back of my mind, is that flyer about the lecture I am missing. Violence. Belief and violence. Harvey changed what we believe about the human body. Hawking changed what we believe about the universe. At another time or in another place, both would have had all forms of violence visited upon them precisely because they challenged existing beliefs. What is it about belief – scientific, theological or political – that ferments such profound emotions? Why are differences in what we believe the principal generator of large scale violence? Belief and violence. Perhaps Steven Pinker of Cambridge (USA) has the answer?