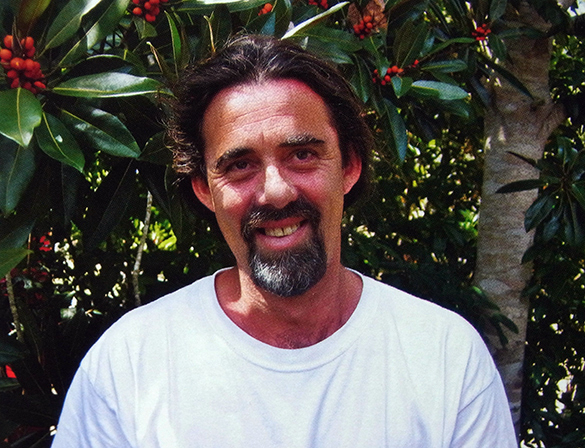

I am back in Tropical North Queensland in Kuranda. The township is a small but internationally renowned destination that sits atop a mountain ridge surrounded by the oldest rainforests on Earth. By day it’s a tourist mecca of art galleries, a famous hippie market, zoos, eateries and craft shops. By night the indigenous Australians claim back the empty streets. I am here once again to visit David Stacey in his studio.

As I walk in, my friend David is applying acrylic paint to a large, colourful and incredibly complex painting. Tourists dawdle past perusing his works on the walls. A woman asks as if in disbelief “Did you paint this?” Others just go straight through to the indoor market beyond. How does David feel about painting in public? This new activity, plus a subtle change that I detect in his work, prompts me to think about a third article about him and his work for Talking Beautiful Stuff.

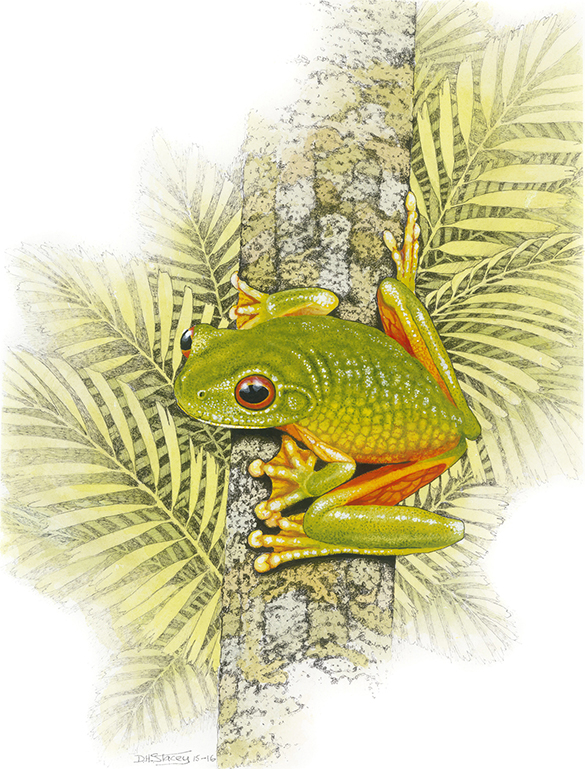

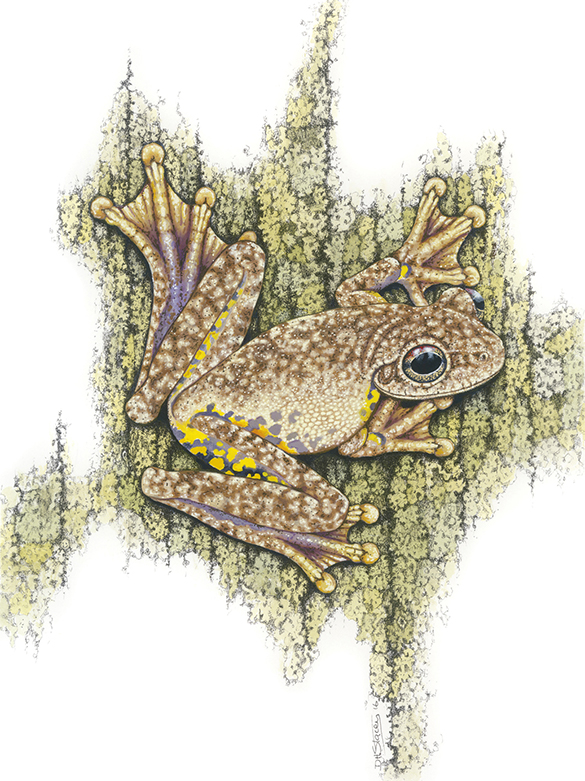

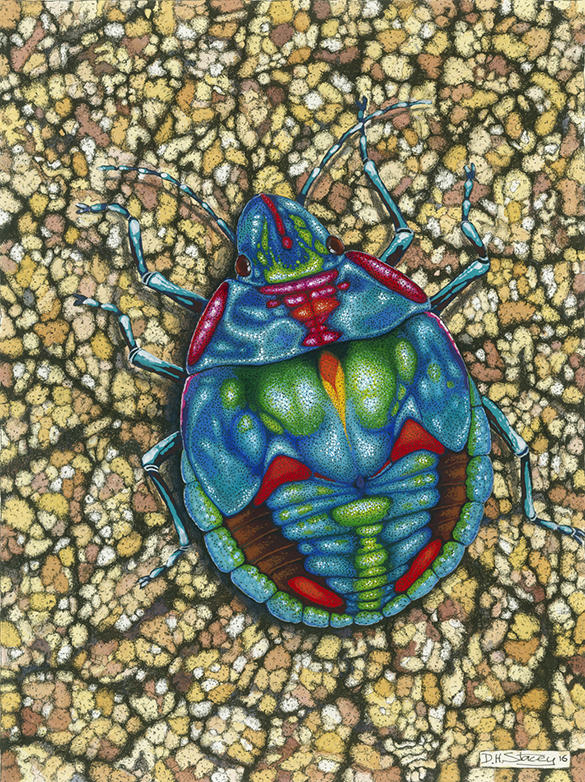

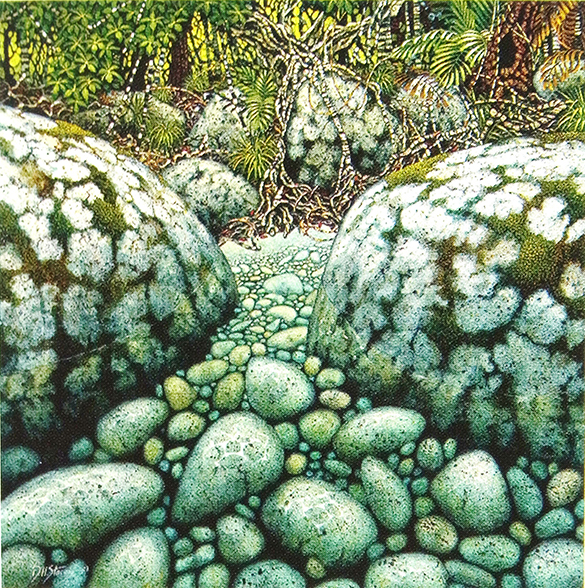

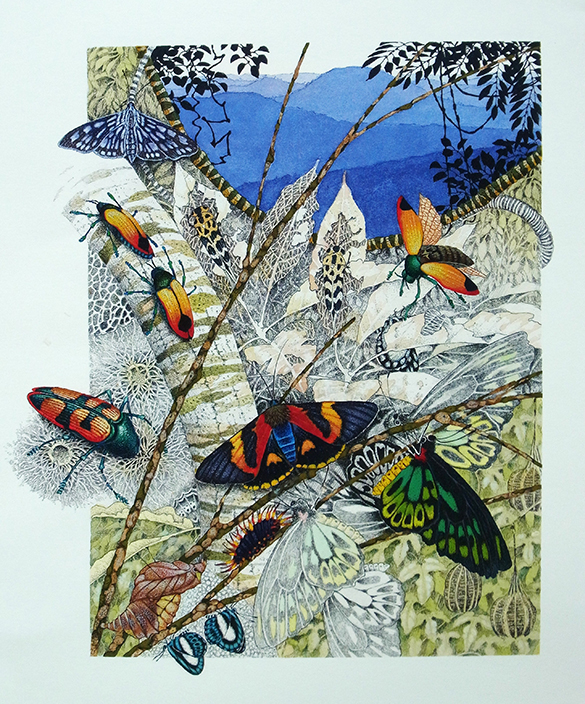

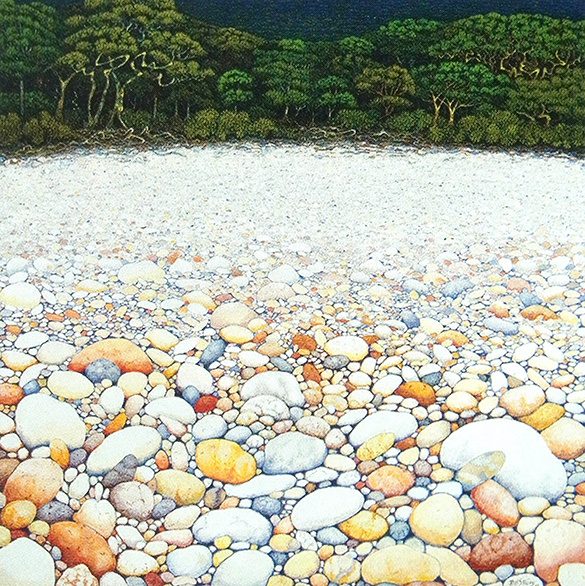

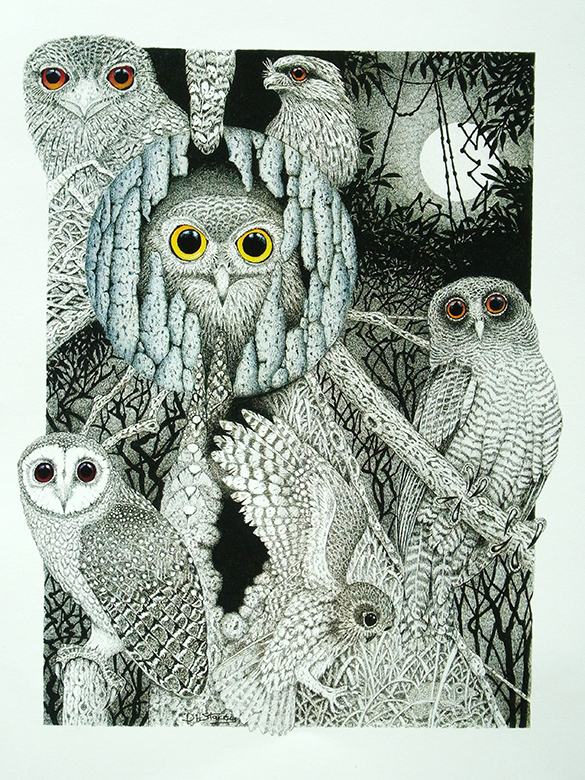

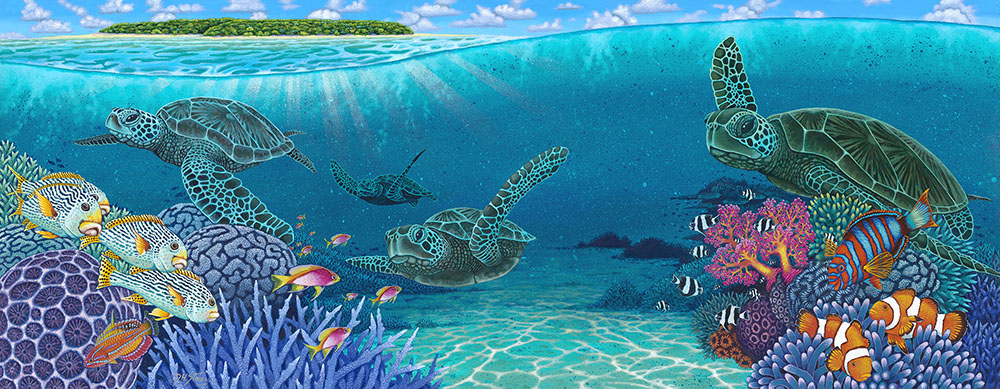

I look around at his new works. The guy has a prodigious output! They are larger and more colourful, if that were possible. There are fewer species’ portraits and more surreal, dreamlike paintings. It is subtle and he agrees that he has evolved in some way. However, the busy gallery is no place for digging a bit deeper so David invites me to go ‘bush’ with him on his next walk deep in the rainforest of the Atherton Tablelands.

A few days later, in khaki and with backpacks filled with water and tucker, we enter the trackless rainforest near Malanda. David has just told me how he was once lost in the bush south of Cairns for three days and, on top, nearly died after being bitten by a venomous Red-bellied Black Snake. I admit to being nervous. I too have been lost in forests. I’d like to avoid a repeat.

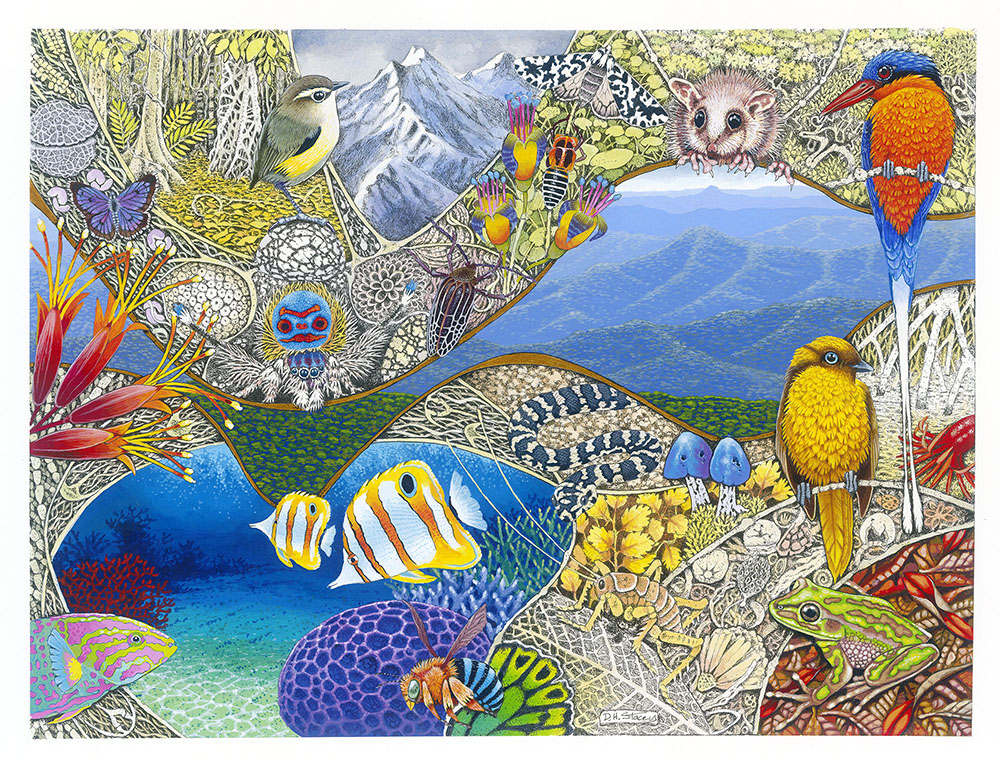

We chat as we go. With apparent ease, David finds the exact place where, years ago, he had discovered the extraordinary twin towers of the bower built by the male Golden Bowerbird. We sit and observe this beautiful rare bird at work. On navigating back out of the forest, David constantly points out things of interest: leaves, flowers, fruits, droppings, tree bark, insects and birds calling from the canopy. The eye of this artist-naturalist misses nothing. I am an obsessive natural historian and can tell you that David Stacey knows his stuff! This knowledge and love of his native flora, fauna, landscape and ecologies shines out from his work. I am privileged to watch and learn from this very private man, now in his true element.

Here’s the Golden Bowerbird in one of David’s new paintings. That’s him sitting right above the frog!

Next stop is the home of a Tablelands animal carer who rescued a possum joey after its mother had been road-killed. My job is to photograph the animal in various poses and take close-ups of its anatomy. David is planning a painting that will include this animal; accurate detail of species is part of the power and beauty of his work. The Green Ringtail Possum is endemic to the high canopy of the region’s rainforest. Having this incredible creature climbing over me is thrilling. In many people’s opinion, it is the most beautiful of mammals. I cannot disagree.

So what did we talk about as the day’s adventure unfolded? David does not enjoy painting in public. Constant questioning and repetition of the questions interrupt him. People touch his work, jostle him and get too close. He has to man the gallery nevertheless. Painting at the same time increases his output and he recognises that observing him with brush in hand creates more interest in his very particular beautiful stuff.

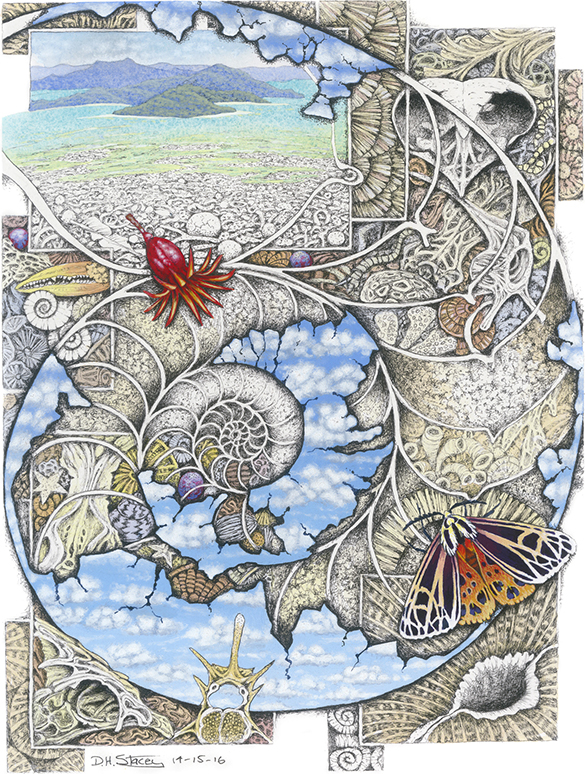

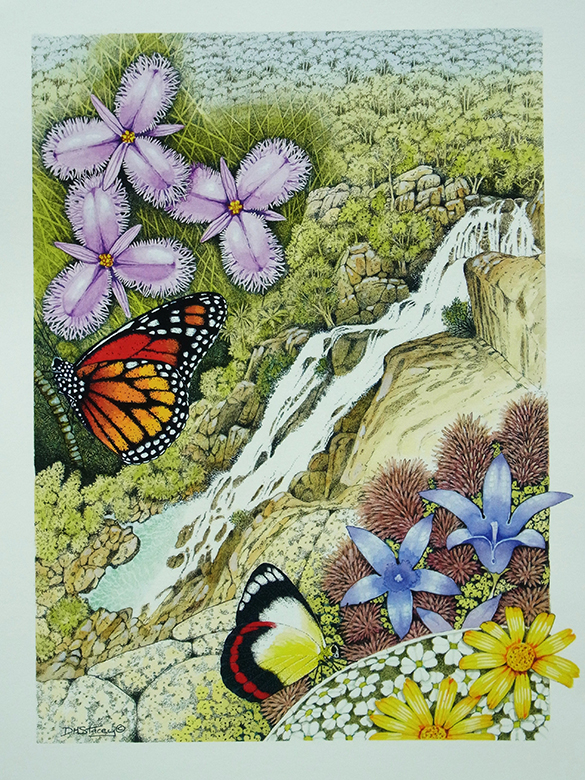

Technique intrigues me and I wanted to know how David achieves the smoky mist effect in this painting. He uses an old, worn-out brush in a ‘feathering’ way. Ingenious! There was me thinking airbrush!

We discussed the similarities and differences in our working practices and attitudes to our creativity. This was revealing. I call achieving accuracy at every stage of the work “keeping my eye on the ball.” He calls it “keeping my hands on the reins.” In terms of the ego we differ. I need accolades to boost my credibility and self-confidence. David wants to have a place in art history: his “legacy.” He wants it to be “significant, unique and original.” He has pretty much achieved that. A “Stacey” is instantly recognised, but above all, admired. However, I wanted to know what he meant by “significant.”

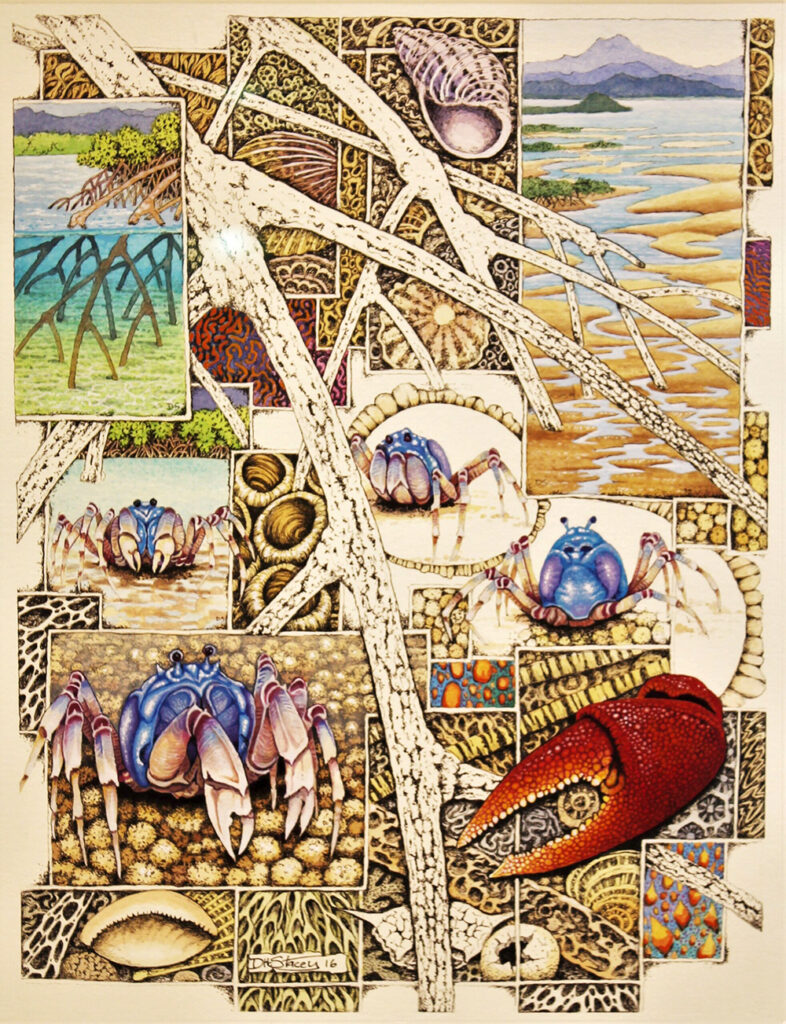

He is happy to explain what is “significant” about his new work. Before, he would paint the landscapes and species because he was inspired by his interest in and love for them. Now that inspiration is underpinned by a profound concern for the state of the planet. He feels that he is now driven by a need to inform by expressing the beauty of his subject matter. He tells me he is “informing through art as a catalyst for change in attitude.” He uses the terms “visual literacy” and “stories through images.”

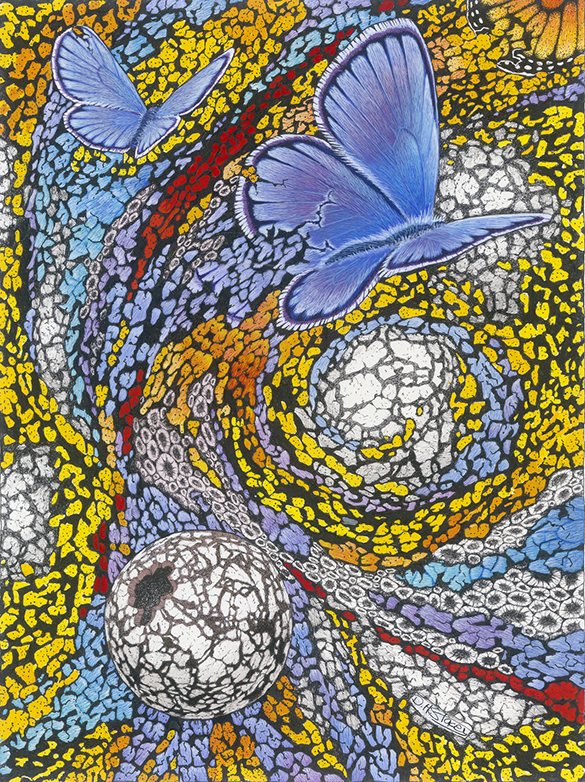

This makes sense to me as I could see it working in the larger, more surreal works that he is creating. “Surreal” is his description; he explains it as ‘juxtaposing different aspects by a form of collage or montage. This, he says, gives more value for money. There are more aspects and subjects to look at and because of this more can be hidden; this then allows the viewer to a more open and personal interpretation. However, he adds, more can also be revealed, and that includes more obvious messages, stories and information. He always places importance in his own meanings within the work.

I am now back in the UK. David sends me a photo of the painting he was working on. He tells me that he didn’t enjoy doing it. Well, the world will enjoy it. Like its creator, it is definitely significant, unique and original.

Thank you for everything David. I wish you and Sandy the very best for the future.