I visited Tate Britain last weekend. The current LS Lowry exhibition is sublime. Go and see it! There’s really not much that I could post on Talking Beautiful Stuff about this artist or his work that has not already been said. Leaving the exhibition exhilarated, I thought I would take a look at what else this sober and venerable British institution had to offer.

I walked into a tastefully but dramatically lit room that, at first glance, might house a Musée Barbier-Mueller exibition. People wandered around between the thirty-four “primitive” masks, carvings and icons. I couldn’t work out why these other visitors were laughing. There was something else going on here; something that made me take a second and then a third look at these objects.

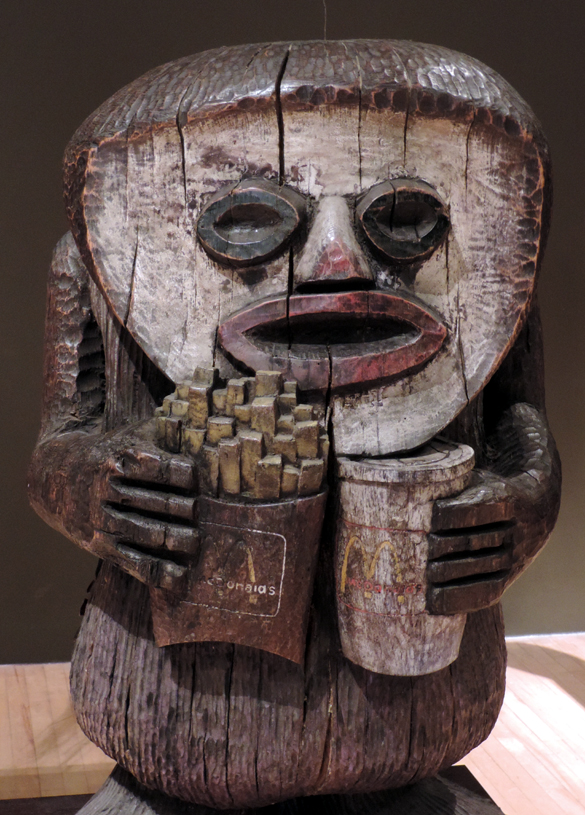

A press release accompanying the first exhibition of The Chapman Family Collection in 2002 at London’s White Cube gallery stated it was “an extraordinary collection of rare ethnographic and reliquary fetish objects from the former colonial regions of Camgib, Seirf and Ekoc, which the artists Jake and Dinos Chapman’s family had amassed over seventy years.” In fact, the collection is one work. Just reverse the names of the three tribes, read on and you’ll understand why people were laughing.

Detail from: The Chapman Family Collection by Jake and Dinos Chapman, 2002. Photo thanks to Tate Britain. Note the yellow “M”!

Detail from: The Chapman Family Collection by Jake and Dinos Chapman, 2002. Photo thanks to Tate Britain. Recognise the face?

Detail from: The Chapman Family Collection by Jake and Dinos Chapman, 2002. Photo thanks to Tate Britain. Well… just to make it obvious!

Detail from: The Chapman Family Collection by Jake and Dinos Chapman, 2002. Photo thanks to Tate Britain. This one really made me laugh!

Detail from: The Chapman Family Collection by Jake and Dinos Chapman, 2002. Photo thanks to Tate Britain. This is my favourite!

The Chapman Brothers have been working together since 1991. They are no strangers to controversy. Their subjects have included Naziism and war-time atrocities. I cannot judge whether, by delicious mischief, the Chapman Family Collection succeeds or not in making a coherent statement about the interface of, on one hand, how primitive “art” is displayed and valued; and, on the other hand, modernism, and commercialism. However, this work caused me to laugh and what’s more laugh at Tate Britain. Chapman Brothers – Bravo! Tate Britain – Bravo!