I am in Norwich, England. A fine city! At it’s heart one finds the cathedral and nearby the cobbled and film-set charming Elm Hill. There nestles Mandell’s Gallery; an unpretentious, quiet and tasteful contribution to the city’s cultural on-goings. The current exhibition DRAW is refreshing, unusual and well worth a visit.

Susan Bacon, “Raven” Charcoal and pencil on paper

This eclectic exhibition features the work of people who have come to drawing via the Royal Drawing School. The School’s strapline is “Draw life: learn to see differently.” Fittingly, the first image that catches my eye is Susan Bacon’s “Raven.” It is just so raven-like. I love the way the feathers have that glossy look, the simple but very real representation of the scratchy clawed feet, the setting of the Tower of London and the little ditty about “A Miserly Bird.”

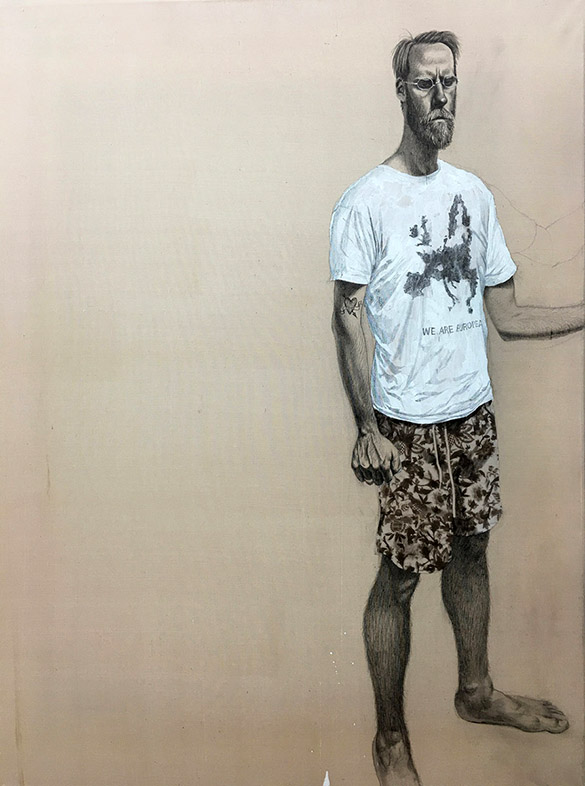

Stuart Pearson Wright, “Self Portrait Brexiting” Pencil, Charcoal and Gouache on silk

I wouldn’t describe this cartoonish self-portrait by Stuart Pearson Wright as beautiful. It is technically accomplished and arresting in its awkwardness. First I notice the clenched fist (anger?) that is as prominent as the gloomy face. Then I ask myself why Wright has placed his casually dressed self partly out of the frame. Then I need an explanation for the outline of another left arm (but this would be his – possibly undecided – drawing right arm seen in his mirror.) The image is full of anxiety, confusion and ambiguity. And then I notice the scribbled map of Europe on the t-shirt and the sub-text “WE ARE EUROPEAN.” And then I re-read the title and it all makes sense and I realise that this is master-class portraiture.

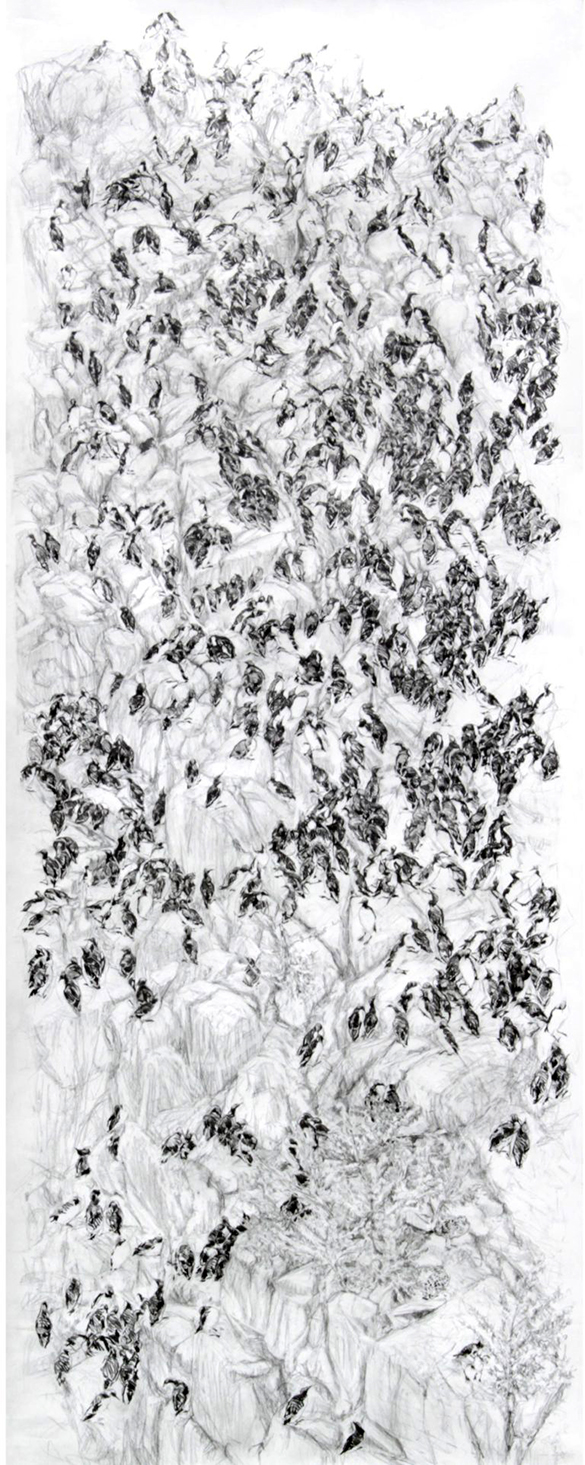

Christopher Wallbank, “Loomery VI” Graphite

One of the exhibition’s curators, Paul Fenner, says about drawing that “Far from being a question of the application of a neutral “skill,” this universal ability to transmute the visible world that surrounds us into another order of visibility is nothing less than a fundamental mystery of our incarnation, our being-in-the-world.” I have to agree when looking at Christopher Wallbank’s truly amazing, tall and detailed drawing of a cliff-hanging guillemot colony.

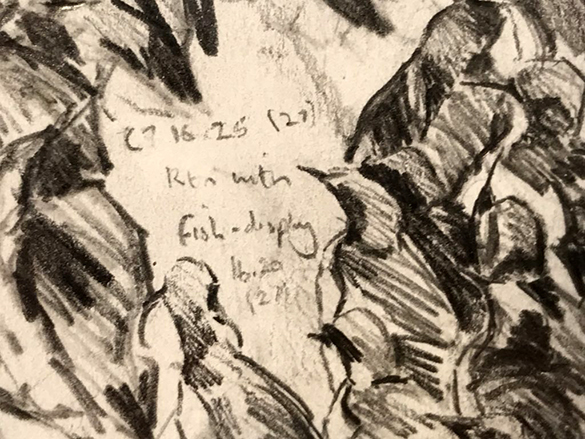

Detail of “Loomery VI”

Wallbank viewed this nesting colony through binoculars. He recorded his observations with multiple drawings and noted the behaviour of the guillemots. Only on close-up are his multiple notes visible as is that amazing ability to capture with the simplest of lines the essential and word-defying features of any given bird species.

Just for reference, here’s a photograph I took recently of a mixed colony of guillemots, razor-bills and falmers at Dunnet Head in Caithness, Scotland.

The exhibition closes on 21st July. So hurry along!