There is something spiritual here. This is hallowed ground. Even in April, the pilgrims are everywhere. Alone, in pairs and in small groups, they emerge on foot from the surrounding narrow grey streets. Some arrive by car and drive slowly along the beach front unable to keep their eyes on the road. Buses discharge them by the dozen. The reaction is the same the moment they first catch sight of that vast area of immaculate rolling green. Mouths gape open in surprise. Then a kind of dreamy smile takes over each face and out come the cameras. Great things have happened here. Hopes have come true; others have been crushed. Even though the wind blows, everybody speaks in hushed tones. You don’t have to hear the voices to know that the devotees come from every corner of the globe.

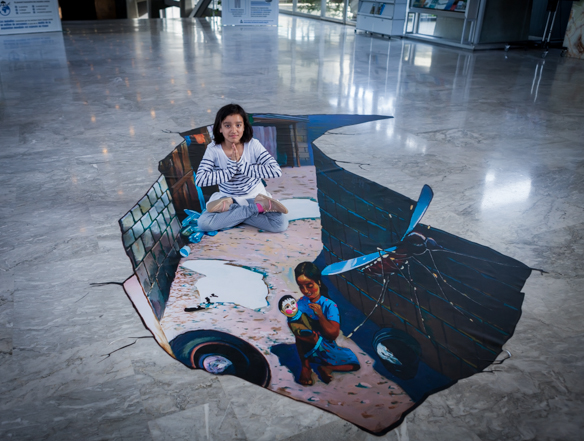

The 18th green of the Old Course at St. Andrews with – viewed from left to right – the “Chariots of Fire” beach, the Old Pavilion, the wee starters office and the Royal and Ancient Golf Club. (The lens shaped shadow just the other side of the flag is cast by the “Valley of Sin.”)

Every great golfer has walked this green mecca on the east coast of Scotland. Every golfer dreams of walking it. As I write, I hear the non-golfing reader groan. Surely Talking Beautiful Stuff is not going to describe a golf course as “beautiful”? Well…. yes! This blog is dedicated to the many and varied aspects of the human ability to design and create beautiful stuff. The Old Course at St. Andrews is a thing of beauty and not only because it’s the most famous golf course in the world. What also makes it beautiful is that it’s the mother of all modern courses. It is the original. It is unique. It is steeped in history and tradition. It is the home of golf and the Open Championship. After mother nature, the man to whom its creation – and the modern idea of golf – is attributed is Old Tom Morris.

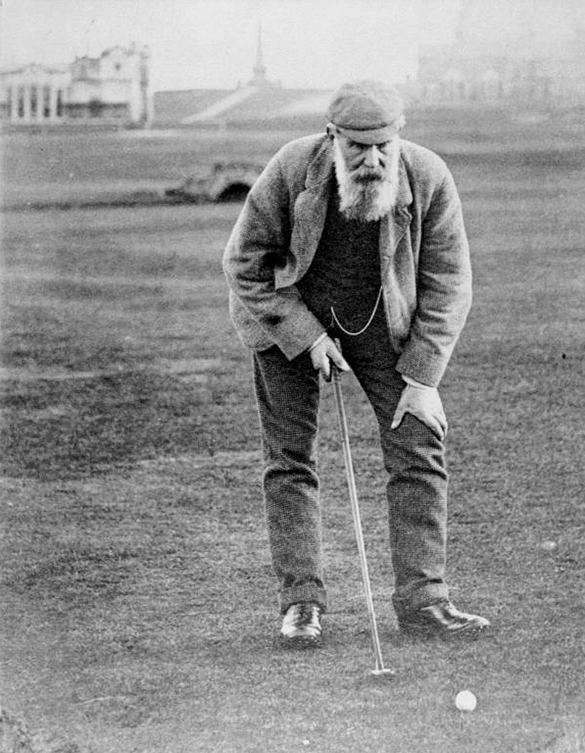

Old Tom Morris in 1905. Behind him is the Royal and Ancient Golf Club and the Swilcan Bridge. Photographer unknown.

It is known that golf – or something resembling it – and football were played on the St. Andrews links since the early fifteenth century. (At the time both pastimes were forbidden by Royal decree!) It is also known that in 1764, there were 22 holes that were played in both directions. The four shortest holes were later combined into two making the now-standard 18 holes. In 1863, the Royal and Ancient Golf Club employed Thomas MItchell Morris Senior (1821 – 1908) to redesign the St. Andrews golf links. Old Tom found the links in a poor state. He set about fashioning the huge greens, widening the fairways and putting in the hundred or so bunkers. He also developed the ideas of dressing greens with sand to improve the quality of the grass and having a separate teeing ground for each hole.

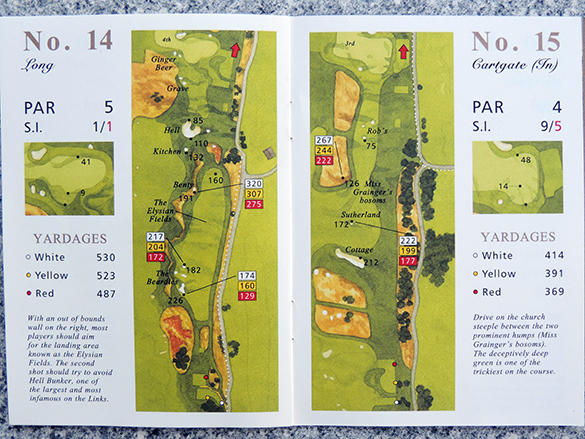

The massive double green shared by the 3rd (white flag) and 15th (red flag) holes with the Cartgate bunker.

Ask a grizzled Old Course caddy why there are eighteen holes you will most likely hear that there are 18 drams of whiskey in a whiskey bottle! The same caddy will cite Old Tom’s fascination with eighteen because the great double greens have been so laid out that the 2nd is paired with the 16th, the 3rd with the 15th, the 4th with the 14th and so on each pair adding up to 18. Whether this is by chance or a design masterstroke, we will never know. It leaves only four single greens: the 1st (“Burn”) enticing the ball of the unwary or unskilful golfer into the Swilcan burn, the 9th (“End” – where Old Tom seems to have had a small lapse of imagination,) the 17th “Road” of (in)famous bunker fame and the O so glorious 18th (“Tom Morris”) and its Valley of Sin.

Holes 14 and 15 on the Old Course guide. Copyright: St Andrews links 2014, artwork by Lee Wybranski.

The stylish course guide for the visiting golfer shows just how full of quirks the Old Course is. Every hole, bunker or feature has a name. On the 14th hole (“Long”) you are advised to drive for the Elysian fields and at all costs, to avoid Hell Bunker. On the 15th hole (“Cartgate”) you have to pass over the Cottage and Sutherland bunkers aiming just left of Miss Granger’s bosoms. (And while we are on the Old Course’s lexicon, I was very happy that my drive on the 16th hole avoided the Principal’s Nose and, on the 18th hole, bounced just beyond Granny Clarke’s Wynd!)

Many other courses bear Old Tom Morris’s name and character; they include Prestwick, Muirfield, Royal Dornoch, Royal North Devon and South Uist. However, he was much more than a course designer. He was a club maker, ball maker, green-keeper and, amazingly, a prestigious golfer winning the Open Championship no less than four times. What a guy!

The most wonderful and unexpected part of the Old Course story is that it is still public land. Golf and its terrain do not have to be exclusive. International visitors are perplexed. I hear an American voice: “Excuse me, but can I really walk on the course? I mean, like, this is St. Andrews!” Not only is it public land but it is closed for play on Sundays. Anyone can stroll around and – wait for this – walk their dogs. This offers a stress-free opportunity to visit some of the notable features especially those to be avoided.

And if your name is drawn on the ballot to play the Old Course – another wonderfully democratic aspect of the St Andrews golf scene – you find yourself standing on the first tee, in front of the Royal and Ancient Club House with dozens of on-lookers, knees a-tremble, praying that you will get your first shot of the day away without embarrassing yourself. I did not embarrass myself but I couldn’t help feeling that some of the voices that mumbled “nice shot” came up from that ancient turf.

Whatever happens from then on in your round, my advice would be to simply enjoy it and don’t worry too much about how you score on those sacred holes. That is until the 18th. You are back in the historic arena. In your mind, the whole golfing world past and present is watching. From the tee, it looks like the widest fairway in the world. “Aim at the R&A clock” says the caddy, Ian. A few minutes later, I am approaching the most famous green in the world. My second shot, a firm wedge into the easterly wind, lands ten feet from the pin. A few casual observers hanging over the white boundary fence applaud half-heartedly. But I feel a little weak with relief. And we were just playing for beer! Without success, I try to imagine making that shot and one putt for £000,000s.

Afterlife or no, if you design or create something beautiful, some small part of your spirit lives on for the benefit of others. The Old Course at St Andrews, the traditions born here and the tens of thousands of golfers who visit each year are testament to the spirit of Old Tom Morris. He lives on and in style.