Geneva, Wednesday 22 April 2020

Today, the staying-at-home and the news are getting to me. I feel a need to get away from the whole pandemic thing. I hope you’ll join me for a trip to the other side of the world for a spot of fishing and painting. More than a little self-indulgent, I know.

The brown trout Salmo trutta! This fish has been a fascination for me throughout my life. They don’t get much better than this at 9.5 pounds and my fishing buddies in Jacindaland will be able to tell from the photo what this beauty had for dinner. Go on, guys, use the “M” word!! (BTW.. I let the fish go.) The brown trout is a noble beast and the big ‘uns are difficult to catch on a fly. Isaac Walton, author of the Compleat Angler (1653) published a recipe for baked trout; the first line reads “First, catch your trout.”

So, a free style, open air painting to match the catch.

Step 1. Find place to inspire painting.

Step 2. Prepare raw canvas with white acrylic. Arrange stones in sort of fishy form.

Step 3. Dribble paint of unlikely colours over stones. Blue wash above the fishy form. Green wash below. (Remember to keep stones for friend’s rockery.)

Step 4. Place bigger stones as if on river bottom and dribble brown / green paint between them.

Step 5. Let dry whilst having lunch in the sun and investigating lake edge for signs of trout.

Step 6. Remove all stones.

Step 7. Use imagination to find the fish.

Step 8. Consider rubbish bin.

Step 9. In desperation, cover with very dilute dark blue wash.

Step 10. Ask friendly gallery in Reefton, South Island to stretch it up.

Step 11. Call it “Trout.”

We went for a cycle ride down to Geneva’s lake side this evening. A beautiful sunset. People are out and about as if it’s a summer Sunday. It seems like everyone expects some lifting of isolation measures in the next days.

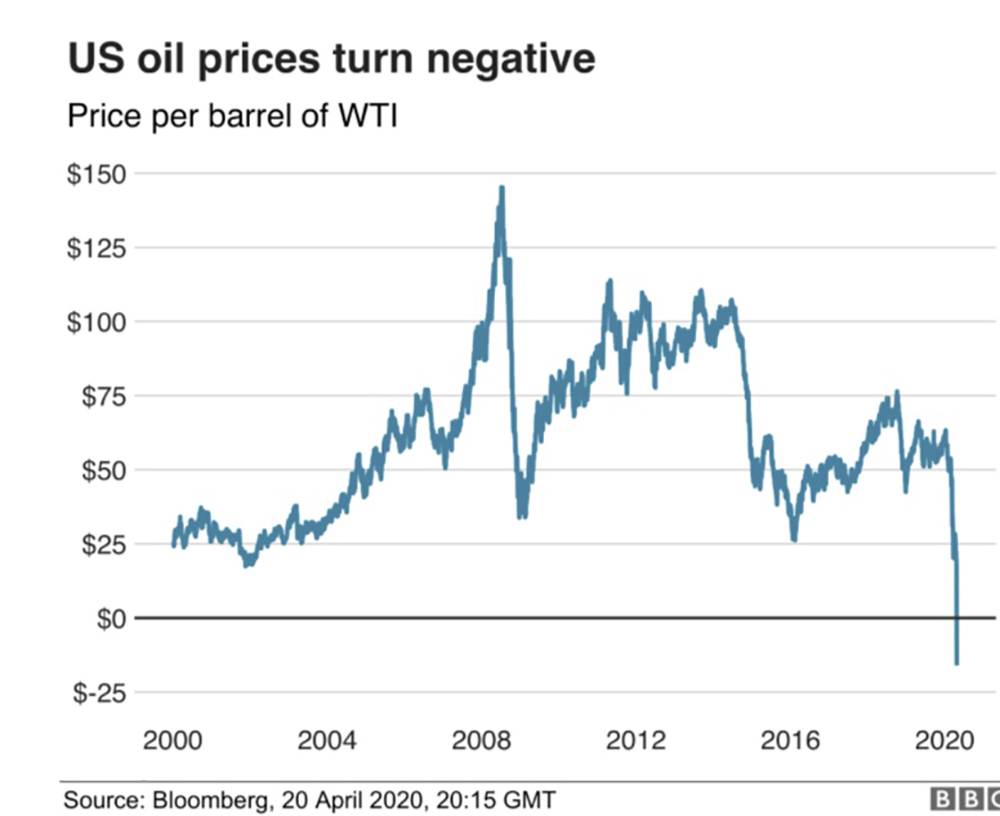

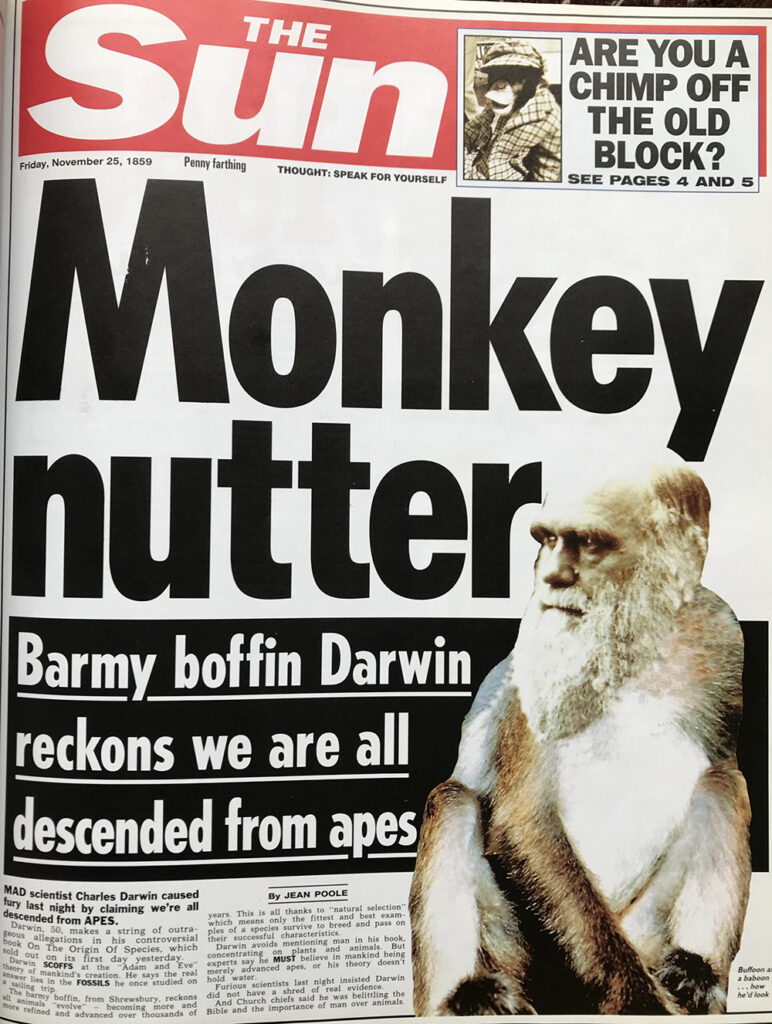

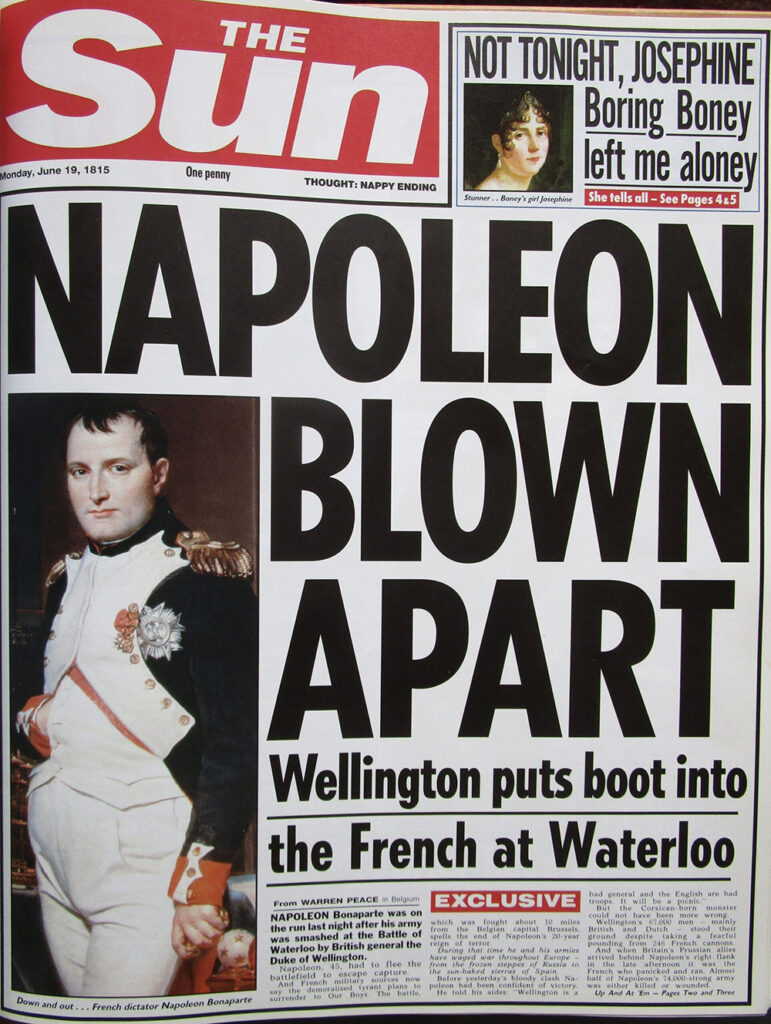

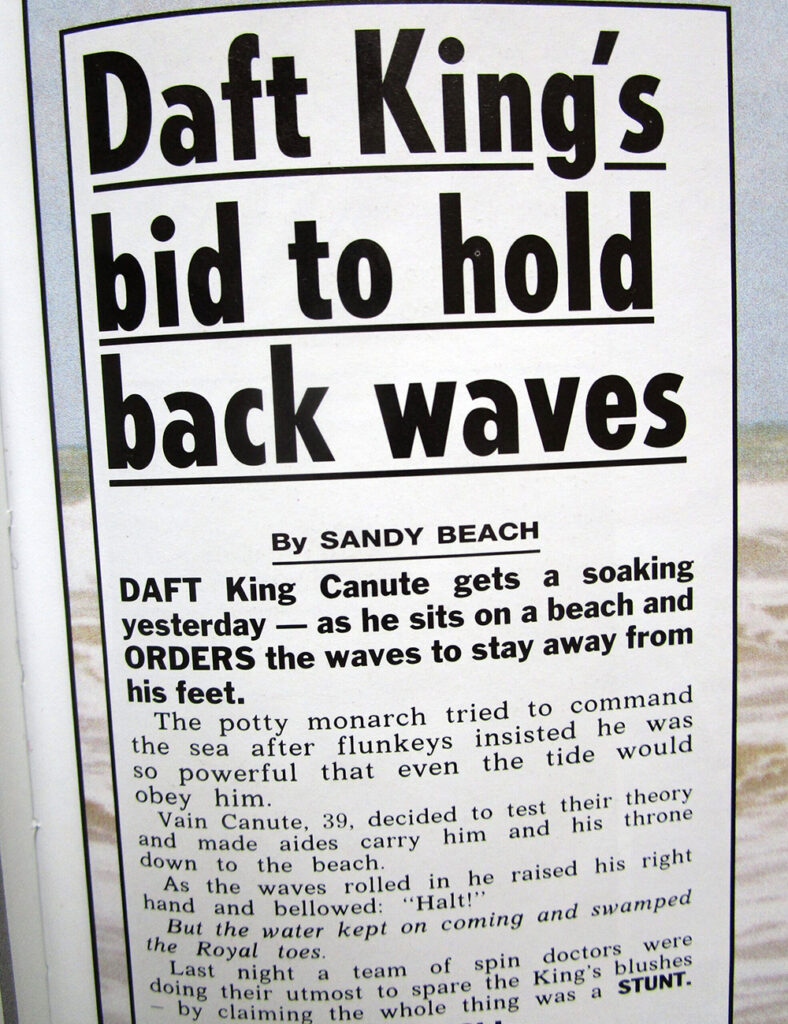

I just looked at the BBC news. I knew that would be a mistake.