Isaac calls me. “Hey, buddy, what going on with the advertising spaces in Geneva? Half the billboards are just covered with plain white paper. People have started to paint on them.” I grab my camera, hop on my bike and head into town.

My first stop is right outside the University Hospital. Brilliant! This rapidotriptych by p2 recalls those ubiquitous questionnaires. So…. after your visit to hospital, were you unsatisfied, more-or-less satisfied or very satisfied with your treatment?

It’s cold. I freewheel down to the Plain Palais area.

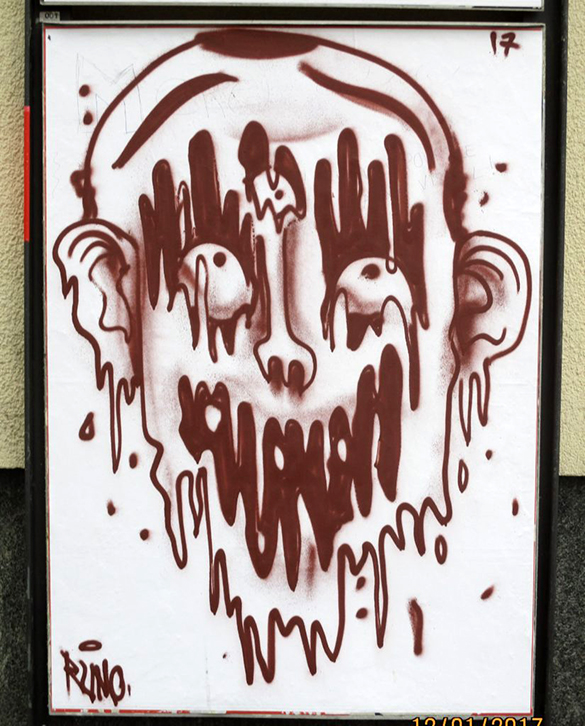

I find a bit of inner warmth in this rather beautifully designed rainbow-love-eye. Next to it is RZINO’s grotesque zombie face.

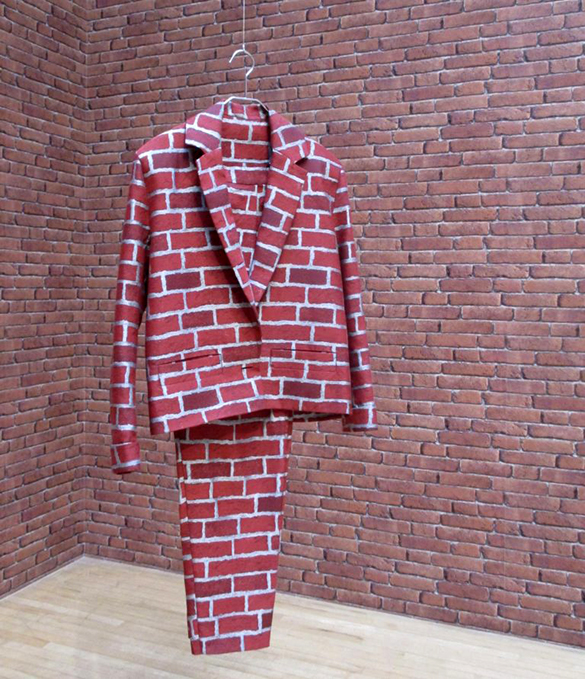

This is fascinating. I think it most likely that an ad agency has gone bust and not having material to stick up has simply painted its billboards white. I’m a sucker for street painting but there’s always the reasonable debate whether such work is beautiful stuff or vandalism. In my view, if someone leaves open white spaces like this all-around town, then those shadowy figures armed with brush or spray can would reasonably see this as an invitation to set about their business. It’s difficult to call this vandalism; my pendulum of judgement swings towards beautiful stuff.

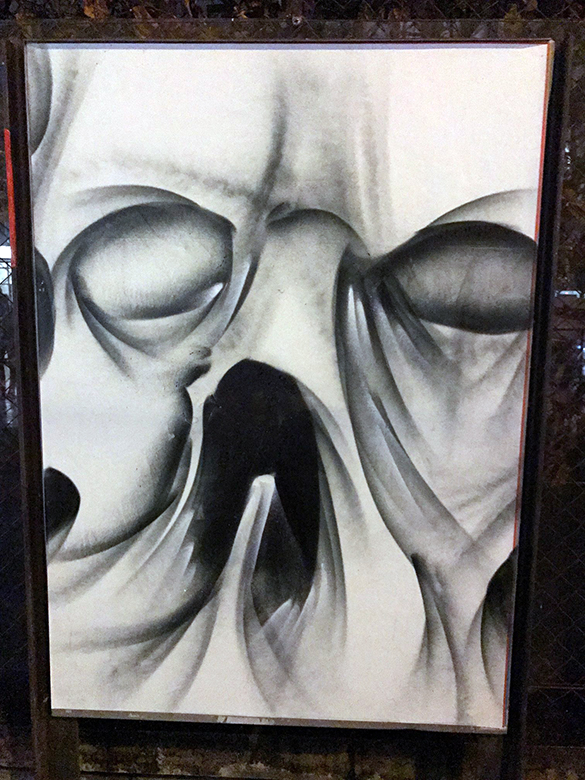

This is by “Charles drawin'”?? Clever! Is his work the outcome of natural selection? Charles has been busy; he has covered about twenty billboards. His slick, rapid brush strokes hang between abstract and the figurative. Here, I sort of see a lady running in billowing skirts with a dog hurrying along beside her. I’ve seen less interesting stuff in the most exclusive of galleries.

And take a look at this! @CRBZ.TYPO has covered the white with mat black and then overlain sumptuous interwoven arabesque golden curves. I am reminded of the liveries of exclusive Middlle-Eastern airlines. Amazing to encounter this “on the street.”

I head over to the other side of town. I find two billboards taken over by half a sun.

In orbit around our blazing sun are three planets. The blue planet (Earth), the red planet (Mars) and what is obviously a bigger Saturn. A lonely little voice says “Allo”!? reflecting our constant search – or hope – for some kind of cosmic life-form that, we believe, will understand our greeting and respond appropriately. I also love the little random splashes of blue paint. A little bit of chaos theory thrown in?

What is happening on these cold white ad spaces is really exciting. It has a raw appeal. It’s straight from the guts. At the same time, much of it is technically accomplished. (It beats the edndless ads for health and beauty spas, visiting circuses, luxury watches and political parties.) What makes this different from other “art forms” is that it results from people doing their beautiful stuff unbidden and unpaid. Many of us would not even recognise it as “art” (whatever that might be.) I reflect on some aboriginal rock paintings I saw last year in Australia and, in turn, all those famous cave paintings that cause such excitement. So, here’s the question: If there’s no element of vandalism, does filling these empty billboards represent a primal human urge to leave a mark for others? A mark that indicates what I see, what I fear, what I hope for or what I believe in? Are we looking at the equivalent of cave paintings in the twenty-first century?

Maybe other readers of Talking Beautiful Stuff have taken an interest in what is happening on our streets? Have you got photos of other billboards that you think we should see? Send them to us. We’ll try and find your favourite, contact the modern cave-painter and do a feature on his or her work.

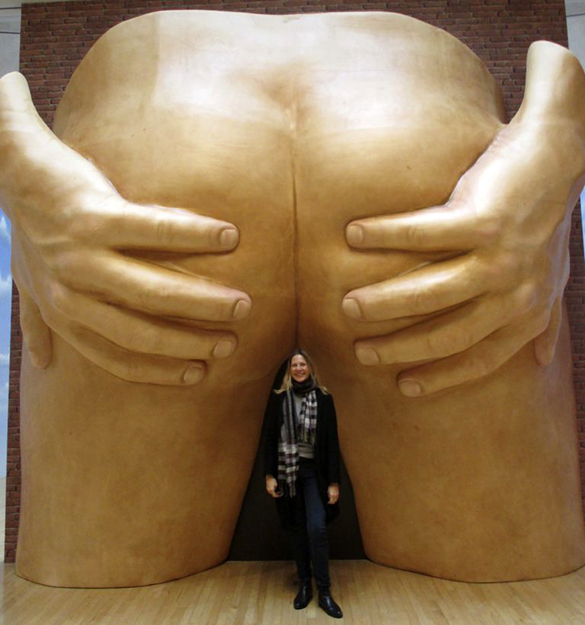

Before you go….. look what stared out at me from the shadows as I waited for a tram last night!