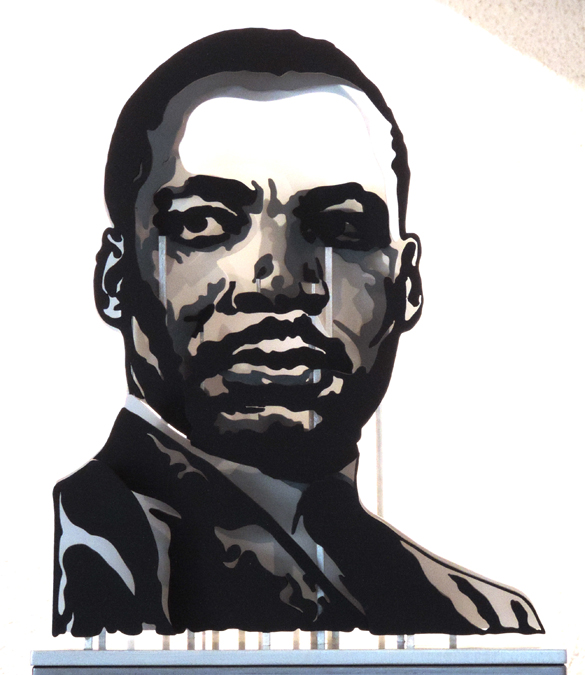

On entering Galerie I.D, I was not immediately bowled over by Michael Kalish’s iconic portraits. That came a few minutes later. Instead, snippets of childhood conversations with my mother repeated in my head. 1962: “Who is she?” I asked. “A very beautiful lady – an actress!” 1963: “Who is he?” I asked. “The President of the United States. A very powerful man” came the reply. “Why are you upset?” I persisted. Mother shook her head. “I don’t know!” 1968: Who is he?” I asked. “A very important black man.”

These tragic American events carried such a gravity that news of them crossed the Atlantic in minutes and reached my very English parents via our grainy black and white television. Nobody could have known how the importance of these deaths would evolve over decades in lockstep with their symbolism.

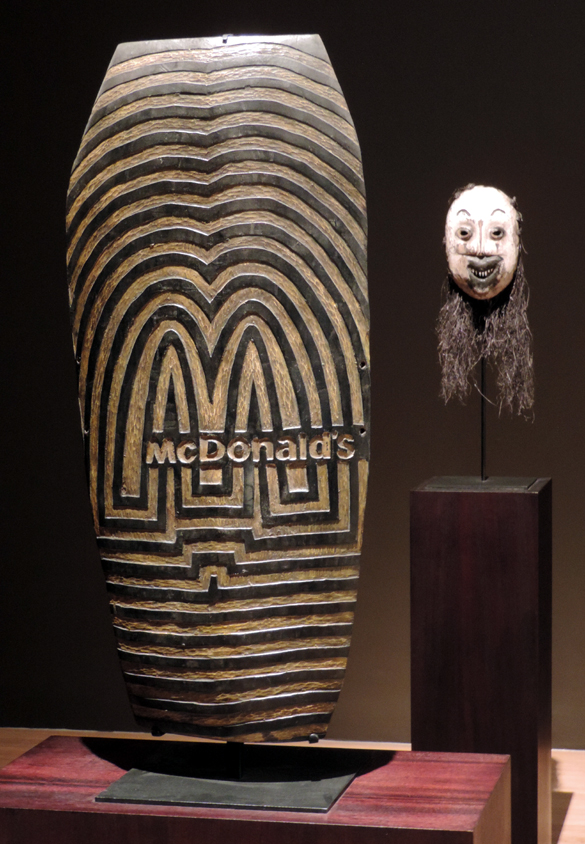

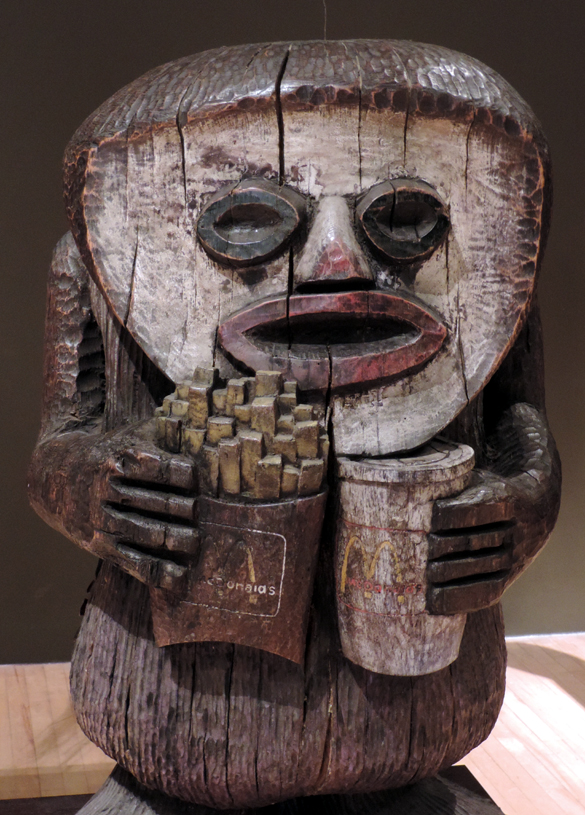

Michael Kalish is based in Los Angeles. He is young, accomplished and ascendant. He is unafraid to strut a big creative stage. The backdrop to that stage is bittersweet and loud Americana meets Pop meets Big Auto. His preferred medium – with which he has made his name – is cut-out car registration plates. The resulting iconic works are tinny-made-solid-by-rivet, tactile and, frankly, fun. They are, nevertheless, evocative of a world-changing era that resonates today. Kalish’s major creations include a twelve-meter high portrait-monument to Muhammad Ali made of 1,300 boxing bags and five miles of steel cable. His work is unsponsored.

This current exhibition at Galerie I.D is wonderful and strangely moving. It speaks to the cultural boom, global dominance and underlying nervousness of the United States of the 1960s. I am privileged to post here on Talking Beautiful Stuff images from the first ever showing of Kalish’s most recent sculpture-portrait. Scroll down! Be bowled over!

Michael Kalish is a name you will hear more of. If you are in Geneva, seize the opportunity to see his work. It’ll soon be gone.

All works shown here are by Michael Kalish, 2013. Photographs published with kind permission of Galerie I.D.