The Ariana Museum is a sumptuous, impressive structure set back from Avenue de la Paix in Geneva. It was built in 1884 by Gustave Riviliod to house his private collection of objets d’art. He named it after his mother, Ariane de la Rive. It’s formal title now is the Swiss Museum of Ceramics and Glass. From the outside, you would be forgiven for thinking it is some sort of presidential palace (except that Switzerland has no President!). The interior does not disappoint; its polished marbled arches and smooth granite columns are imposing. It is quiet and cool. Entrance to the permanent collection is free. The staff are very polite.

If I am honest, a whole museum dedicated to glass and ceramics has never really “floated my boat” as the Americans would say. But one thing takes me back there regularly: its permanent collection contains a marble bust that is the most beautiful sculpture in existence. There, I’ve said it! And when you go and see it – as you should – you will agree. She lives. If you watch her for long enough, her eyes open for a quick peak at you! And just imagine… this was chipped out of a rock! Luigi! Hat off to you!

“Femme voilée” (Veiled woman) by Luigi Guglielmi (1834-1907).

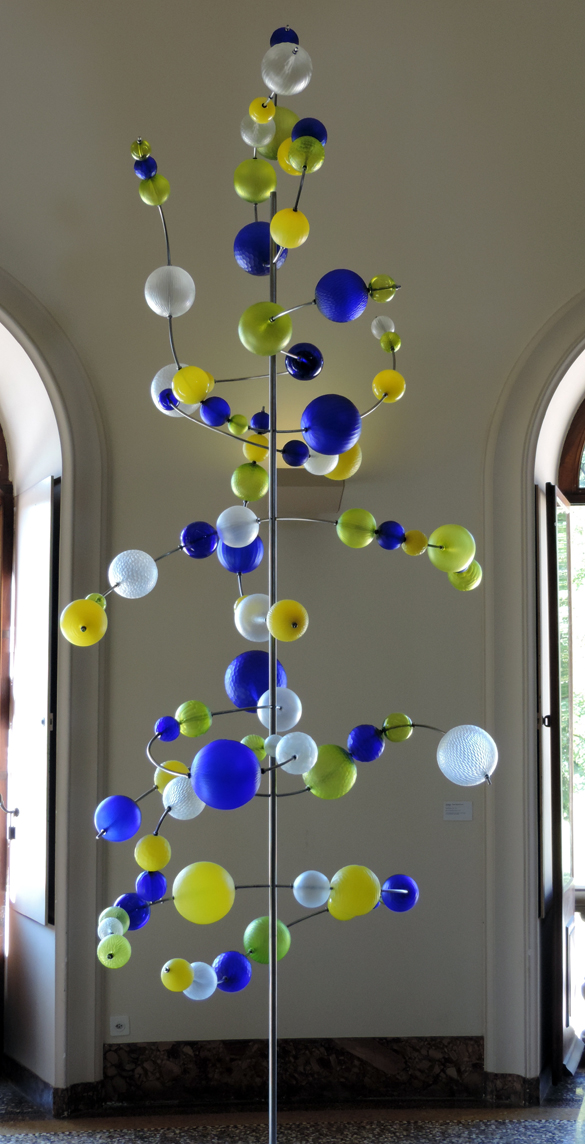

The other work I love is right next to the main entrance. It is elemental, elegant, delicate and kinetic but, at the same time, solid in a weighty, glass-and-steel kind of way.

“Pagan Remembrance” (2008) by Philip Baldwin and Monika Guggisberg.

I go to the Ariana every couple of months or so for a rendez-vous with my veiled lady. I play with the idea of inviting her to lunch at the discrete little restaurant on the first floor. So I cannot really claim that I was going to see the current temporary exhibition: “8 artists & clay.” I decided to have a look. This luscious collection of contemporary ceramics was a total surprise. And it floats my boat! It’s a must see. The extensive basement is dedicated to the work of Claude Champy, Bernard Dejonghe, Philippe Godderidge, Michel Muraour, Setsuko Nagasawa, Daniel Pontoreau and Camille Virot. I am intrigued by their imagination. Their arresting and provocative pieces are generously and very tastefully exhibited. It is calming to wander around them and to soak up the warm colours. The voice of temptation says “Go on, Robin! Nobody will see if you run your hand over those delicious textures!”

In the foreground is Philippe Godderidge’s “Demeures” (2013). The space behind is dedicated to a number of works by Michel Muraour.

The space given over to Bernard Dejonghe features his five black enamalled wall-pieces of “Areshima”(2008).

A mixture of porcelain and orange clay “Sculptures” (2008-2012) by Setsuko Nagasawa.

Upstairs and taking pride of place in this exhibition, is a large collection of the late Jacqueline Lerat’s work. It is an acknowledgement of her revolutionary contribution to modern ceramics. The pieces are warm and earthy but with unexpected little flashes of colour. They have a comfortable appeal as though they would really be happier in people’s homes. I want to pick them up and feel their weightness. (A polite man wearing a white shirt, a dark tie and a radio watches me carefully as I photograph them.)

Sculpture au cercle blanc (1990) & Sculpture et végétaux (1985).

Femme assise au grand chapeau (1962).

Trois pousses verte et un pied rose (2003).

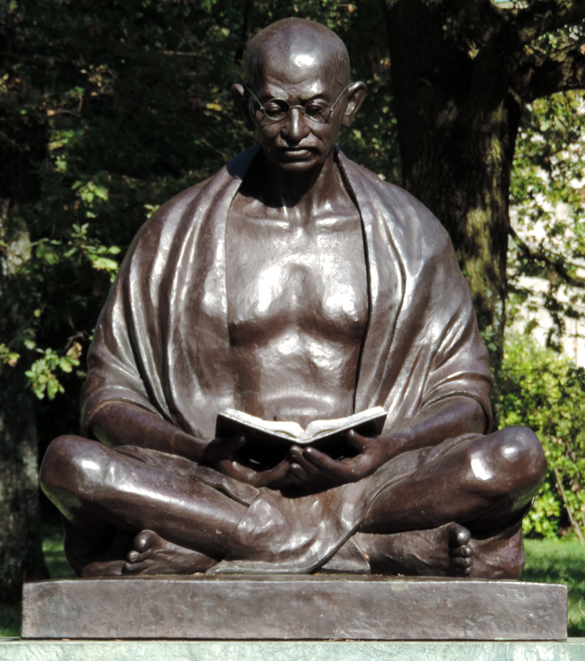

And there’s more… If you want a moment of reflection on leaving the Ariana, you can find a wonderful bronze of Mahatma Ghandi only fifty metres from the front door. It is a gift from the Republic of India to Geneva. Around its base, the grass is worn away by the countless people who stop, reflect and take photos. Perhaps they hope he will briefly lift his eyes from his reading?

“Mahatma Ghandi: My life is my message” by Gautam Pal (2007).

If contemporary ceramics floats your boat, then paddle your way down to the Ariana. You’re in for a quite some surprise. The “8 artists & clay” exhibition closes on 8 September but the veiled woman will still be there.