The entrance to Musée Rath gives on to a noisy Place de Neuve in central Geneva. Behind the enormous oak doors, all is calm and quiet. The staff are, as usual, polite and helpful. They and visitors alike communicate in hushed tones. Everything about the place is clean, sobre, sombre and conservative. Exhibitions are always immaculately curated and the current show “Biens Publics” (Public Collections) is no exception.

Tony Cragg, “Pallet,” 1980, Plastic Objects, Mixed technique

This eclectic collection of contemporary works celebrates twenty years of Geneva’s prestigious Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MAMCO.) No surprise then that the idea for this exhibition came from MAMCO’s charismatic and eloquent director, Christian Bernard. The works on view have been selected from permanent collections of MAMCO, the Museum of Art and History and contemporary art funds of both the City and Canton of Geneva. The first thing that catches my eye is the size, form and ingenuity of Tony Cragg’s “Pallet.”

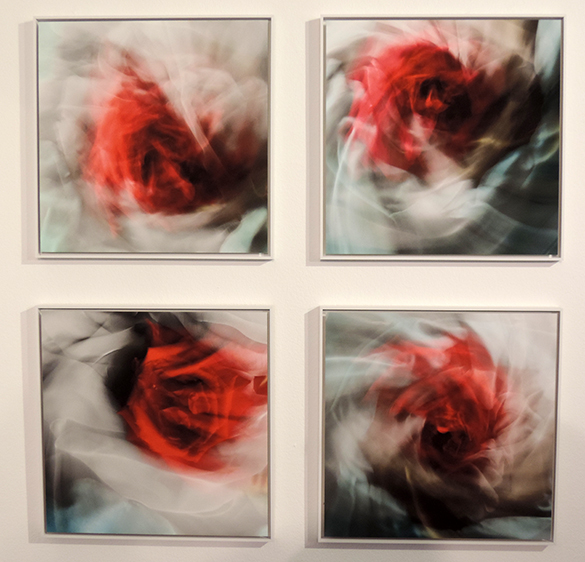

Miriam Cahn, “Zensur,” 2008, Oil on Canvas 80cm x 80cm

“Contemporary art” can be difficult to digest if there is no access to the work’s narrative beyond the title. But then, is the person creating or curating the work playing specifically on its indigestibility? Or maybe the viewer should take each work at face value and invent his or her own narrative? Often, questions-to-self do not yield immediate answers. Whatever, there is always a narrative and it’s always interesting. So I just stroll around with an open mind enjoying the narratives – whether untold, whispered or shouted – of some truly innovative and intriguing beautiful stuff. I love the dark story implied by Miriam Cahn’s “Zensur” (Censorship.) Why is a faceless and rather delicate women in a shimmering red dress black-handedly holding down two downcast and defenseless figures?

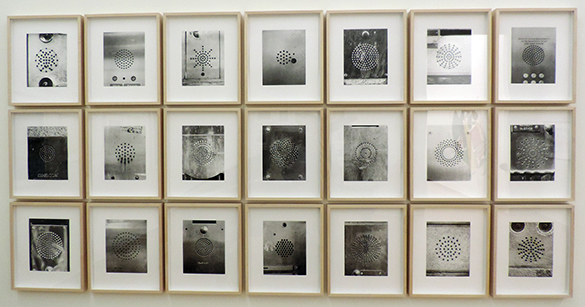

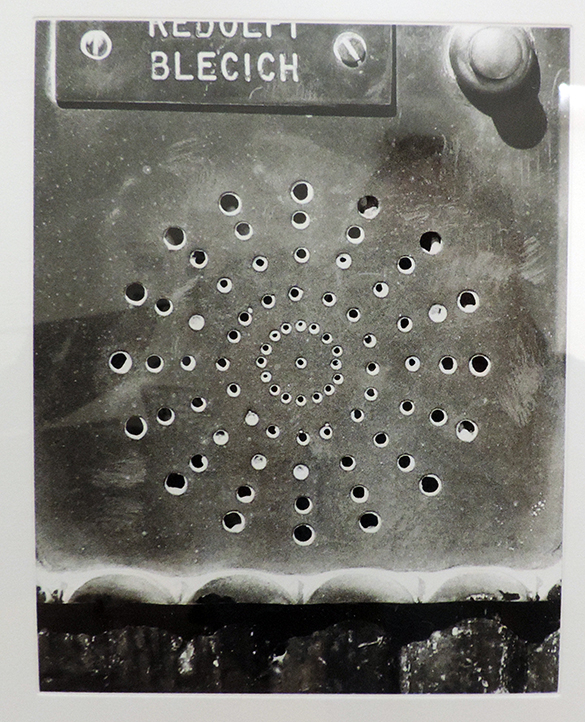

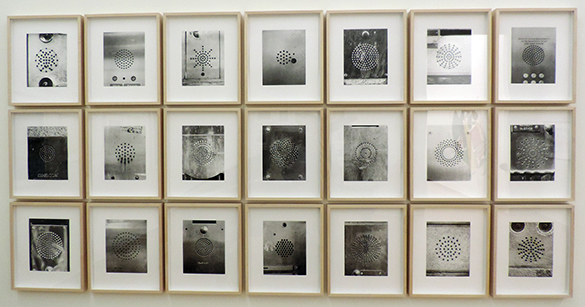

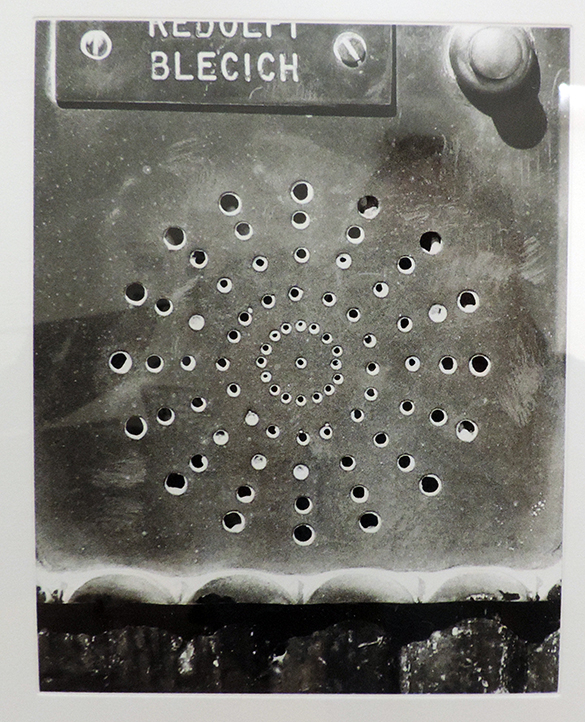

Christian Marclay, “Sound Holes” 2007, 21 photographs

Detail of “Sound Holes”

One room features work by Christian Marclay. He teases us by playing with our senses of vision and hearing; light and sound. I am captivated by his idea of exhibiting a series of photos showing the visual homogeneity of those perforated, sometimes-polished metal plates you hear a reply from – and shout into – when you ring someone’s door bell.

Christian Marclay, “Grand Piano and Mirror” 1994 with (on wall) Christian Marclay, “Rock” “Classic” “New Age” posters, 1994

Here, Marclay has replaced the wires in a grand piano with a mirror. The inside of the lid is mirrored also. The white keys are orange. Whatever he means by this, I find myself walking around it chuckling. I notice five posters on the adjacent wall for what are, at first pass, different concerts. One is for rock, another classical, another for “new age” music etc. Then I notice that the featured musician in every one is none other than the versatile Christian Marclay! Furthermore, all concerts are billed for the same day (28 May) at the same time (19.00) at the same address in Geneva (10, rue des Vieux Grenadiers, Geneva) … that just happens to be the address of MAMCO! What a guy! Bravo, Marclay!

Down the elegant stairs…. Sylvie Fleury, “Lighten” 2008, Neon lights

Gianni Motti, “Think Tank” 2014, 500 shredded pages of confidential documents in plexiglass light-box

On the lower ground level, I find Gianni Motti’s “Think Tank.” The concept is arresting. The written outcome of some patently important thought processes lie in a transparent container on full view to the public. But the documents cannot be read… because they are shredded! But how do I know they really were confidential documents in the first place now they are shredded? Motti gets the last laugh.

One room is dedicated to black and white. It is very cool. I pick one work furthest on the right hand wall. It is Imi Knoebel’s massive and energetic ply-wood “Schlachtenbild” (which translates as “battle picture”) .

Imi Knoebel, “Schlachtenbild” 1991, Lacquer on plywood

Detail of “Schlachtenbild”

Just fabulous! Not wishing to cause offense…. I have an image of Jackson Pollock with a machine tool! I admit to a desire to go out and buy a huge ply-wood board, some black paint and an industrial drill even knowing that I would fail in my attempt to produce anything equivalent.

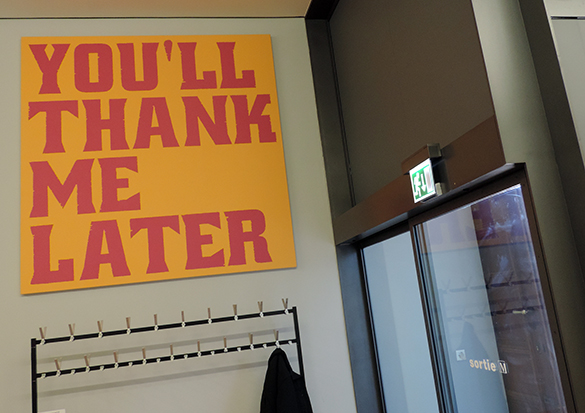

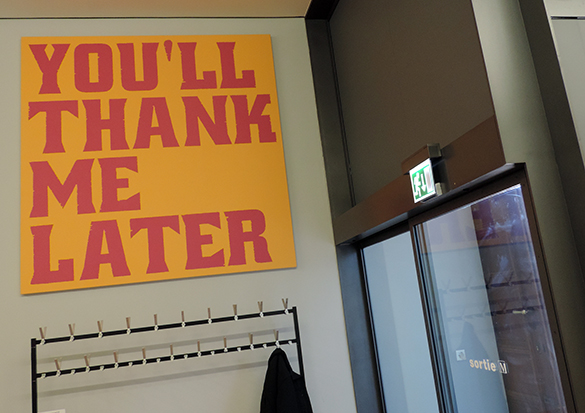

Christian Robert-Tissot. “Untitled: (You’ll Thank Me Later)” 2012, 180cm x 180cm, Acrylic on canvas

Feeling both animated and challenged, I head for the exit. Christian Robert-Tissot’s provocative “You’ll Thank Me Later” is provocatively positioned just above the door. For what will I later thank the painter? For what will I later thank the curator? I find out in a few seconds. Outside, the traffic bustles, jams and hoots. I thank the Musée Rath for a fascinating couple of hours of reflection in the quiet.

With such an exhibition and the growth of Art Geneve, it seems that Geneva becomes an increasingly important centre for “contemporary art”. Whether or not this is your thing, I recommend a visit to these beautiful, intriguing and even amusing “Biens Publics.”