I am in Sweden for a week. I go to see an exhibition by the Brazilian photographer Sebastião Salgado. Question: do I really want to see more images of penguins in cold sea and ice landscapes? Answer: Yes! If they are photographs taken by Sebastião Salgado. I stroll into the Swedish Museum of Photography. My jaw drops. I am simply stunned by the images. This is a masterclass in composition, story telling and developing. “Award-winning” is an inadequate description.

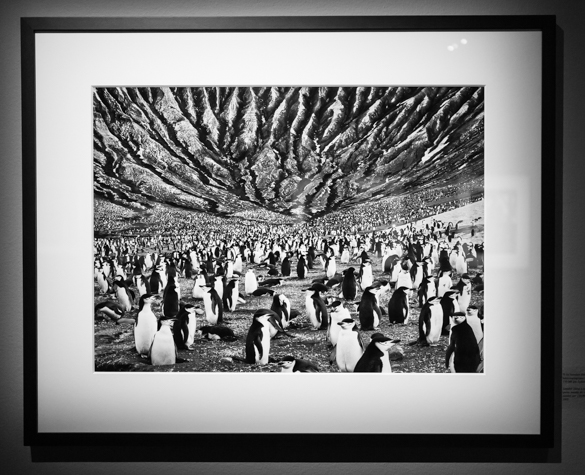

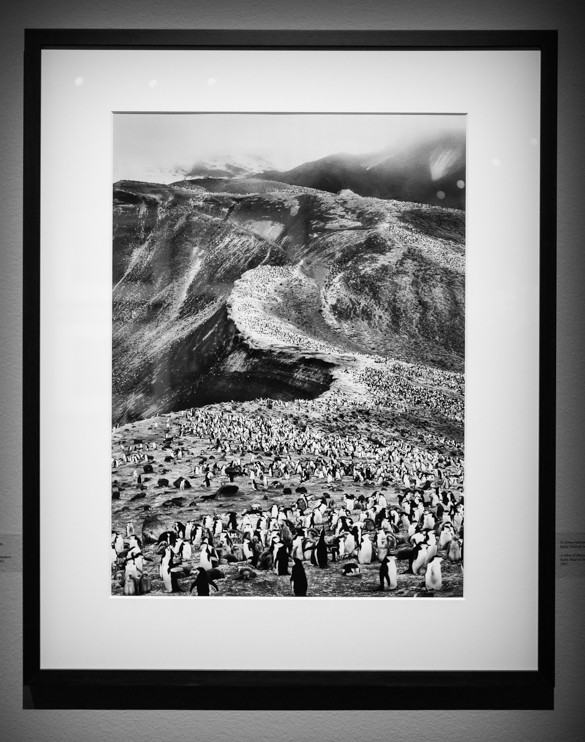

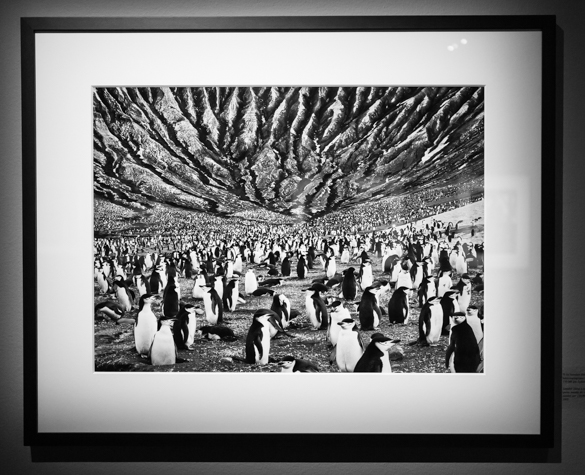

Saunders Island is inhabited by penguins of several different species, notably the chinstrap (Pygoscelis antarctica), which number over 150,000 couples. South Sandwich Islands. 2009.

I take photos of the photos. My camera feels cold. My fingers feel cold. I shiver. How is it possible that these beautiful images take me to the most inhospitable part of the world, focus on a cute fluffy swimming flightless bird and yet somehow what arrives in my mind’s eye is the environmental cost of human over-population?

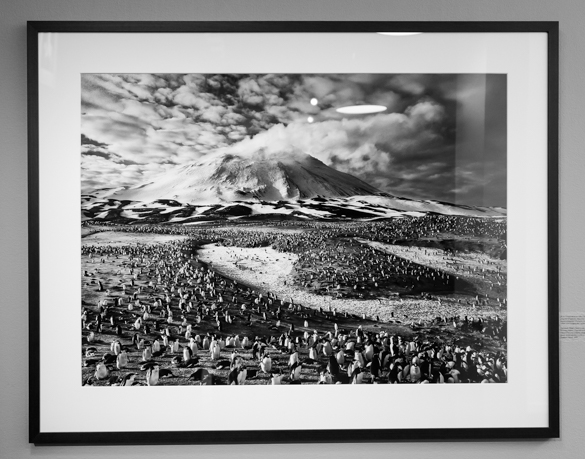

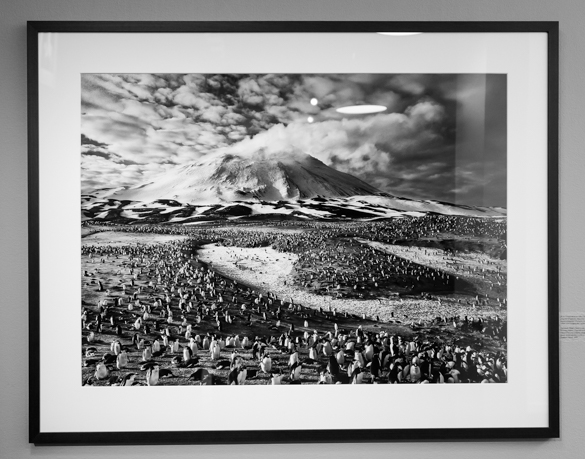

Zavodovski Island is home to some 750,000 couples of chinstrap penguins (Pygoscelis antarctica) as well as a large colony of macaroni penguins (Eudyptes chrysolophus). The island’s active volcano is visible in the background. South Sandwich Islands. 2009.

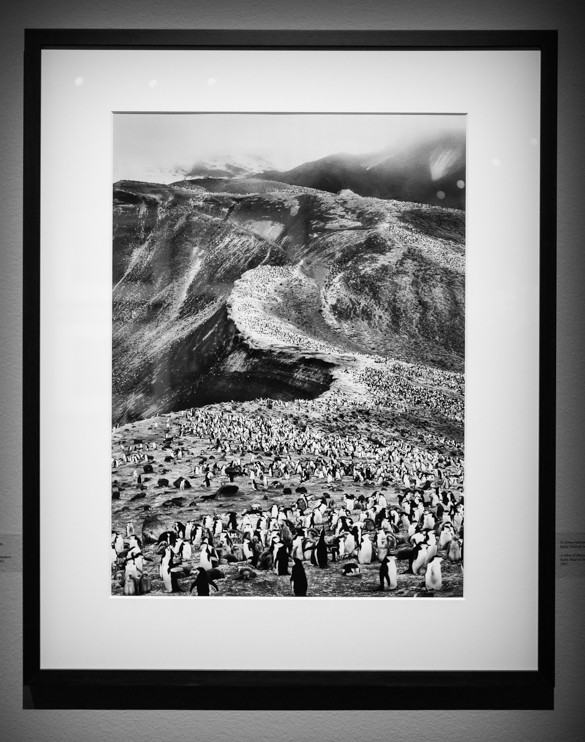

A colony of chinstrap penguins (Pygoscelis antarctica) at Bailey Head on Deception Island. Antarctic Peninsula. 2005.

Back home, I take a look at Sebastião’s website. I have an insight to the work of a truly great photographer but also a photographer whose mission involves putting his work to work. These extraordinary penguin images are part of “Genesis” started in 2004; it is a bigger project about a pristine natural world and invites consideration of human’s interaction with it.

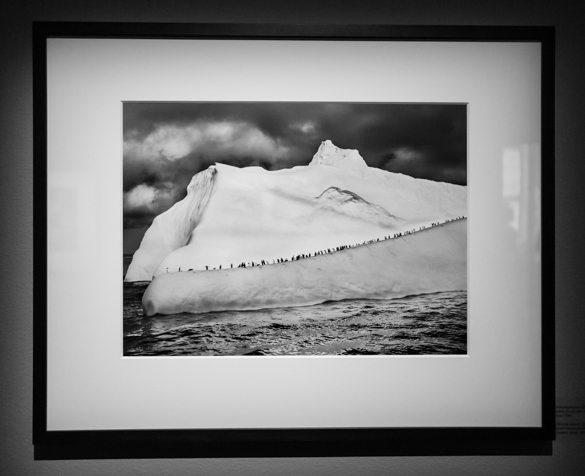

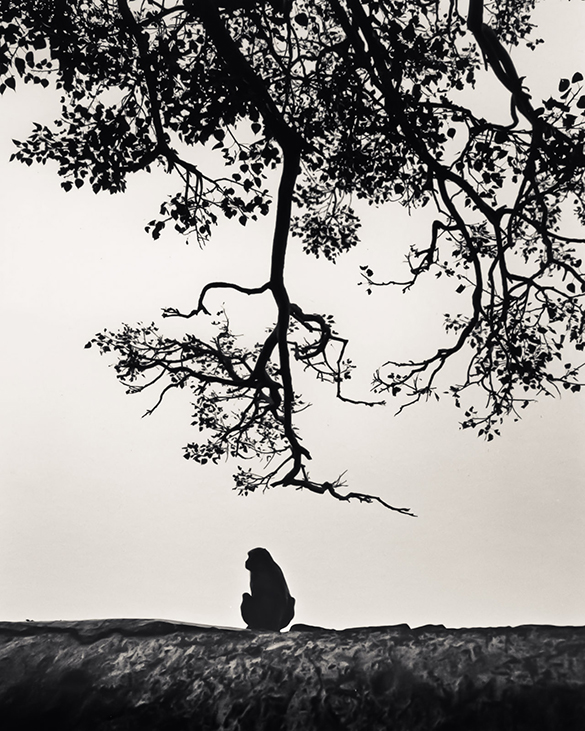

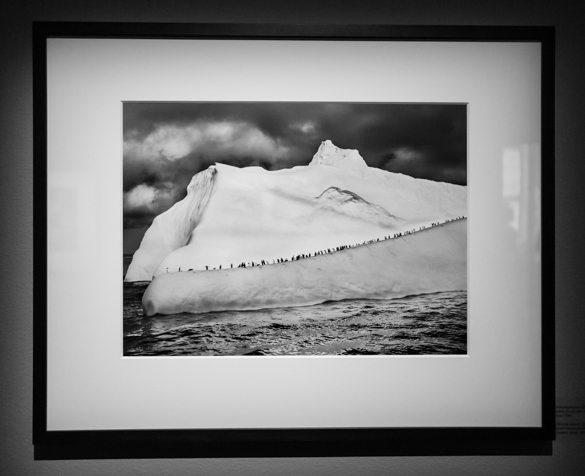

Chinstrap penguins (Pygoscelis antarctica) on an iceberg located between Zavodovski and Visokoi islands. South Sandwich Islands. 2009.

Sebastião’s concerns – and his projects – go further than the environment, his images tell of the dispossessed and injustices in all corners of the globe. They punch. Hence his photo essays carry titles such as “Coffee,” “Migration,” “Polio,” and “Workers.” He also runs a “Smiling Children Project” via his Facebook page. Too sugary? Maybe. But with this morning’s news screaming the awfulness of Iraq, Gaza, Ukraine and Syria, I’m happy to be reminded of a common attribute that binds us social animals together rather than the all too common brutality that pulls us apart. Question: Can images alone bring about change in the world? Answer: Yes! If they are photographs taken by Sebastião Salgado.