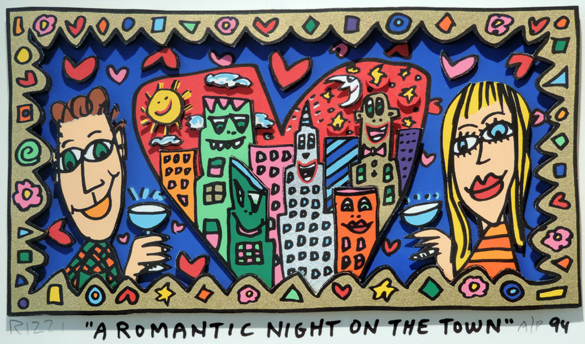

I will never have the opportunity to meet James Rizzi. He died at the age of 61 in 2011. This saddens me. Having discovered some of his last remaining work in Europe at the Galerie I.D in Geneva and having done a little research, I know I would have really liked the guy. His output was prodigious. On-line photos show a mischievous smile. His beautiful stuff makes me happy.

It is said that during his Fine Arts studies in Florida he had classes in painting, printmaking and sculpture. He decided to combine the assignments for all three classes in one work. So he made a drawing and printed it twice. He then hand-coloured both prints and cut out parts of one, mounting the cut-outs on top of the corresponding parts of the other. By using glue and wires, he was able to leave a space between the two. Thus his trademark 3D style was born. (And he got good grades for all three assigments!)

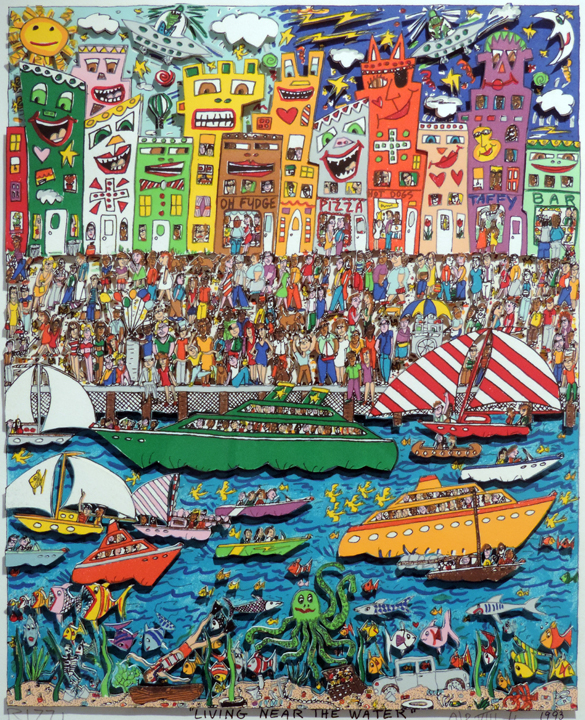

I love the way the buildings in his jumbled cityscapes are colourful characters themselves who observe and find amusement in the mass of colourful human characters. And the detail! In “Living Near the Water,” little green men arrive by flying saucer as yet unnoticed by the heaving crowd. The buildings are happy. The people are happy. The sun is happy. The moon is happy. Humanity is crammed down by the water’s edge or into boats. But we’re left with the feeling that there’s something off-stage. What is the event that has brought such a crush of people and the simultaneous arrival of the aliens?

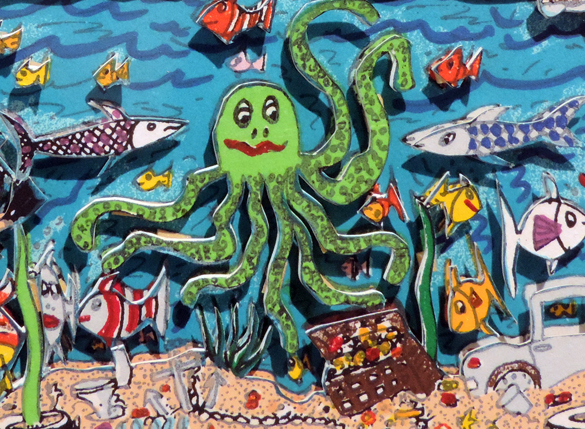

A big green octopus guards a treasure chest on the sea bottom. You could look at this for hours and never discover all the little laugh-out-loud passages.

In 1997, Rizzi was appointed the official artist for the Montreux Jazz Festival. His poster for the event is a masterpiece.

I adore the three cat-back-up singers. You can almost hear them!

Deatail of Poster for Montreux Jazz Festival, 1997 by James Rizzi. Image thanks to Galerie I.D, Geneva.

In his inimmitable style he painted a Lufthansa jet, a VW beetle and whole buildings. In 2008, he won a commission to design stamps for Germany. No problem guessing which one of these three gents is Rizzi!

James Rizzi (on right) at the Inauguration of his German stamps in 2008. Image copyright: Peter Schmelzle.

But my favourite is “Visit My Friendly City.” It amuses and intrigues. Again, we have the characterful sky-scrapers and the little green men in space ships. But what is Rizzi’s humouristic off-stage story here? Why are the buildings all showing such anxiety (except the cool-cat-building)? Do they know that the aliens will not, like tourists, find the city quite so friendly?

In 2006, Glenn O’Brien wrote about Rizzi: “His merry maximalism and delight in delirious detail and elaborate minutiae created a true art brand, a trademark style as recognizable as any in the world.” Although I’ll never discover James Rizzi in person, my visit to Galerie I.D was a delightful discovery of his so instantly recognisable beautiful stuff.