Geneva, 19 December, 2020

David Attenborough has been involved in nature broadcasting for more than 70 years. He is a truly remarkable and inspirational man who, at 94 years-old, has written a truly remarkable and inspirational book “A Life on Our Planet.” I have just finished reading it. Attenborough wags a very authoritative finger at homo sapiens for how, through a perceived need for continual economic growth, we have pretty much destroyed our habitat and that of millions of other species. He provides ample evidence of a looming catastrophe. Given this, he nevertheless offers solutions and even hope. He neatly draws together what needs to be done from an ecological point of view (including an argument for a more plant-based diet,) the imperative for a total shift in how we think of the economy (looking beyond GDP as the sole value of the well-being of a nation) and a human future that is equitable and sustainable. If I were a wannabe politician eyeing the long term, this book would leave me with three words to work into speeches. People, Planet and (not only) Profit.

The boost to our spirits on hearing that COVID-19 vaccines are soon coming on line has been short-lived. The pandemic news has just got a whole lot more complicated and, I fear, worrying. Burgeoning case numbers with associated deaths continue in the US. In the UK and Germany there has been a sudden rise in cases despite lockdown measures. School closures are fiercely debated. We hear that the virus responsible has mutated and may be even more transmissible than before. (Apparently, this is what coronaviruses do. In evolutionary terms, such a virus is much more interested in transmission between its hosts than killing them.) On top, the WHO and China have agreed that an international investigation team will be sent to Wuhan where, supposedly, the virus responsible for COVID-19 first emerged.

And of course, it’s getting to that time of the year. I detest the rampant consumerism that traditionally takes over our lives at this period. Otherwise, I neither like christmas nor dislike it. I just go with the flow. I’m always baffled by how much importance we put on Jesus’s birthday. Christmas in the time of COVID-19 is lining up to be more baffling still. It seems that politicians want to curry favour by allowing us to go shopping and get together with our families in full knowledge that these activities are likely to compound the spread of the COVID-19 virus. Predictions of a new year resurgence are both believable and serious given that case numbers surged in the US as a result of family gatherings for Thanksgiving in November.

I realise that this may all be just too gloomy. So just for grins and giggles, why don’t I populate this black scenario with some online snippets that I’ve found about the economic impact of the pandemic to date. I do not present this material with any expertise in economics.

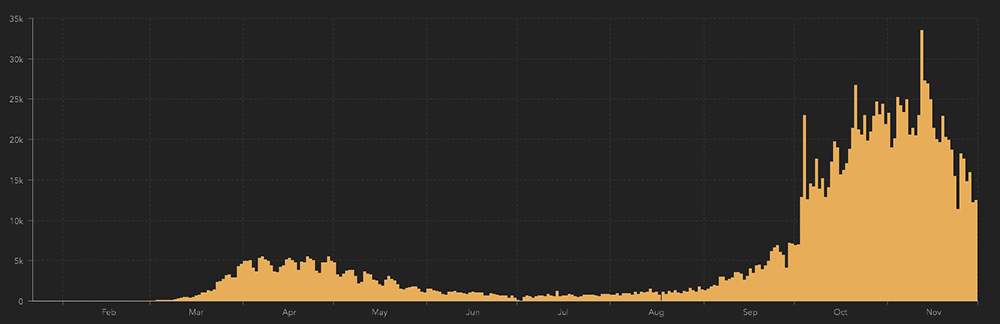

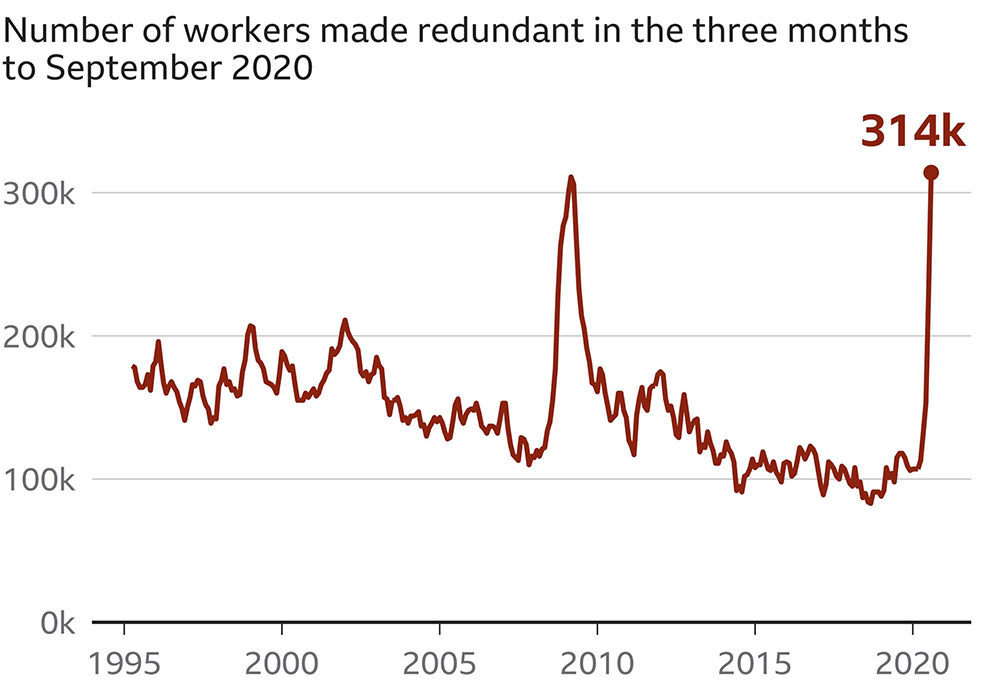

These unemployment figures are heart-breaking. Unemployment has spiked like never before in the US and the UK. By contrast, here in Switzerland, it is reported that those claiming unemployment benefit rose from 2.5% to only 3.2% in the 2nd quarter of the year.

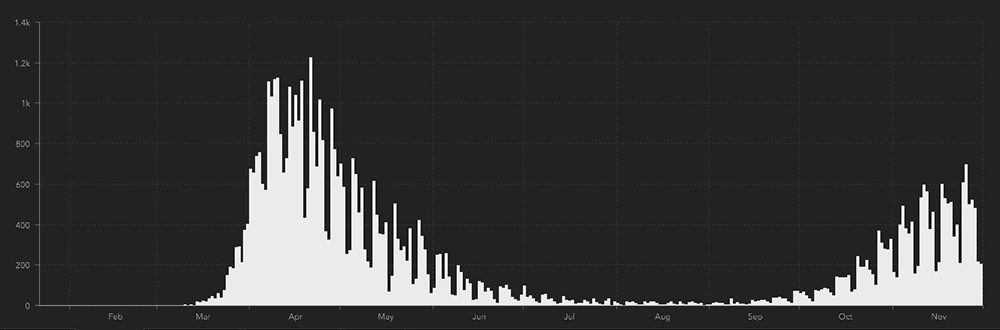

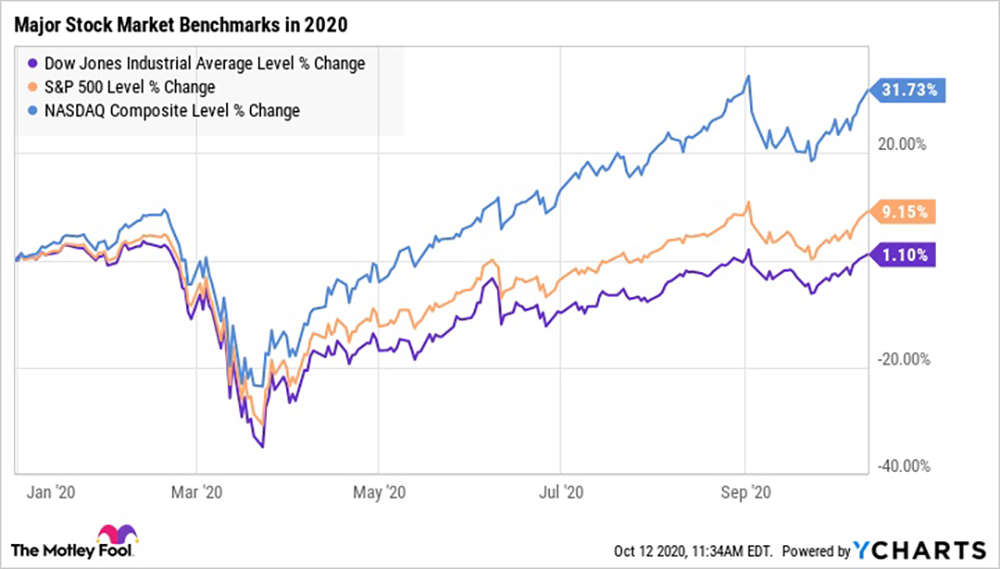

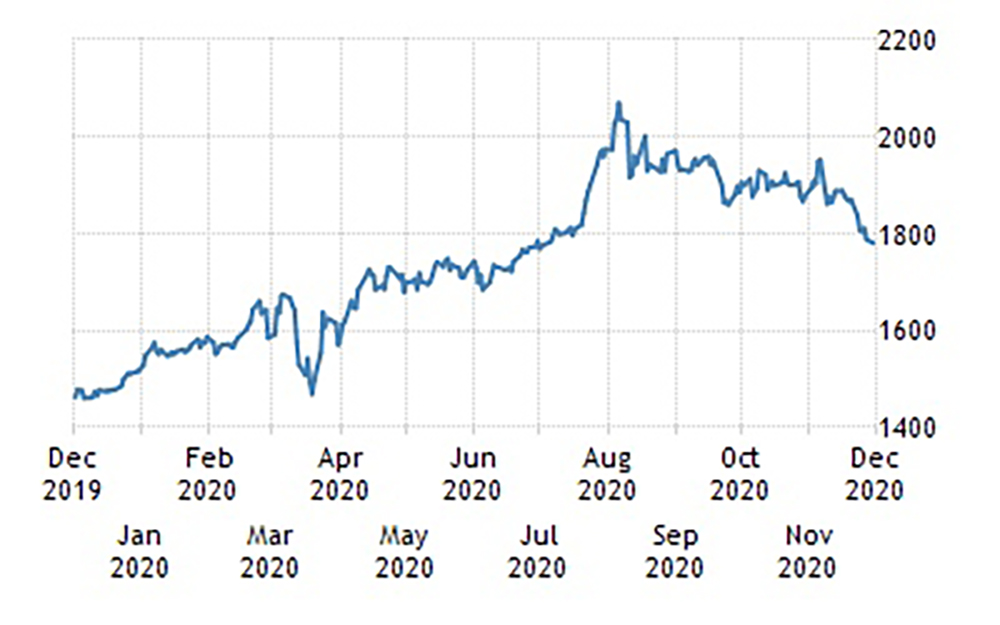

Are the stock markets holding their own?

The markets took quite a hit in March but seem to be getting back on track. Apparently, I am not the only person mystified by this recovery. My friend Tom, who knows about these things, is not sure that this market confidence is sustainable. He’s convinced that the world of high finance is yet to be truly tested by the economic impact of the pandemic.

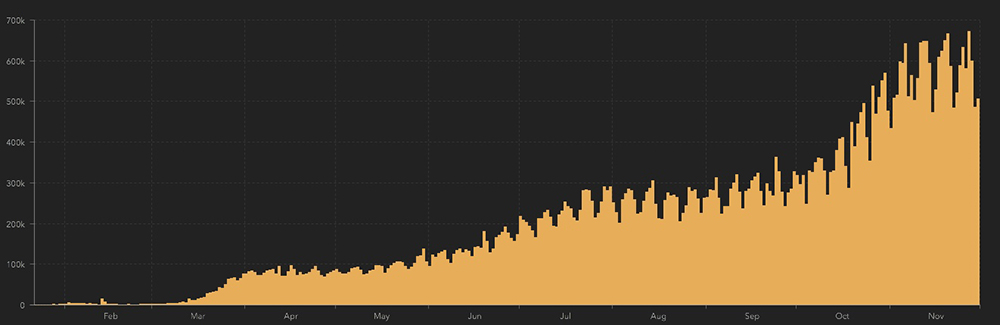

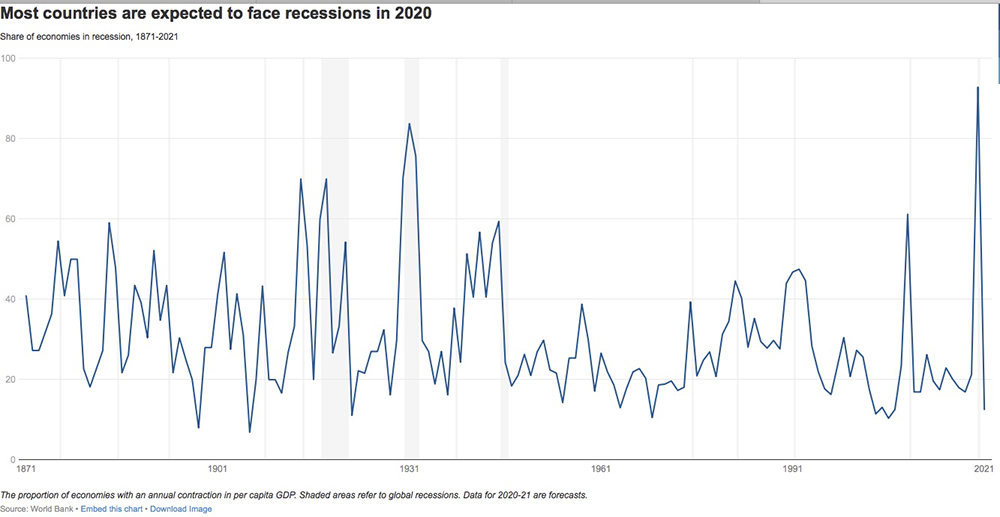

The most sobering of all is a World Bank graph I found yesterday.

This shows that the proportion of countries that will be in recession in 2021 as a result of the pandemic will be over 90%. This is higher than any past recession including the great recession of the 1930s.

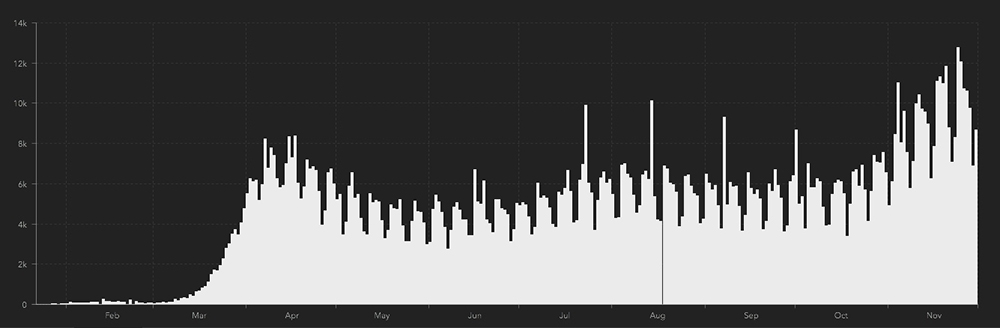

In a global financial crisis, I’ve heard it said that two traditional financial refuges are the Swiss Franc (yay!) and gold. The US dollar has tumbled in relation to the Swiss Franc. (The US now accuses Switzerland of manipulating currency markets.) Gold dipped when the pandemic first hit but in August this year, dollars per ounce of gold hit an all-time high.

This morning, I listened to the third 2020 Reith Lecture “From COVID crisis to Renaissance” delivered by Mark Carney, former Governor of the Bank of England. His theme for this series of lectures is that leaders should reassess “value” beyond pure economic terms. Other more subjective values should be taken into consideration such as fairness, the health and wellbeing of people and the ecological impact of all our activities and lifestyles. He describes the impact of COVID-19 pandemic as the “bill arriving” for lack of resilience preparation, propagating inequities within society and failure to recognise that essential workers are exactly that: essential. The economy was put on “life support” whilst a public health response was mounted. This response has required an unprecedented intrusion into our lives by government. However, Carney points out that this does not indicate that a trade-off exists between the public health response and maintaining a strong economy. Our health, wellbeing and health services should be considered as one set of values and that the economy – another set of values – will not improve until an effective public health response has been put in place. The value to the nation of health workers and, it follows, deaths avoided does not readily translate into economic figures and so should not be sublimated to GDP as a result.

Carney also underlines how the pandemic has hit certain socio-economic groups harder than others. Therefore our ultimate response must engender effective public health measures, addressing societal inequities especially with respect to living standards and education together with plans for an economic recovery. Finally, Carney claims that a similar approach must be adopted by leaders with respect to climate change; something he will be talking about next week.

It seems that Mr Attenborough and Mr Carney are heralds singing off very similar song sheets. If the challenge of addressing COVID-19 helps us face the challenge of climate change then the mantra of any political “renaissance” has to be People, Planet and (not only) Profit.