I spent Christmas with my daughter who lives in Kuranda, a tourist destination in Tropical North Queensland, Australia. This small, unique village sits atop a mountain range cloaked with ancient rainforest and is accessed from the coastal plain below by a colonial style railway, a winding, mountain road and a cable car. In the 1960s its famous Hippie Market established it for tourism; hence its art galleries, souvenir shops, small zoos and various eateries.

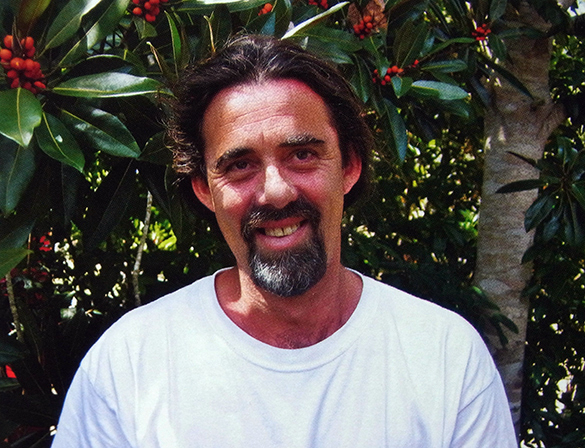

In his small, walkthrough gallery in Kuranda’s centre, David Stacey sat working on a pencil drawing in the corner as I walked through to get coffee in the square beyond. I never got beyond. I was stopped in my tracks by the unusual and amazingly colourful, original paintings and reproductions by Mr Stacey.

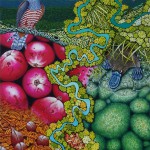

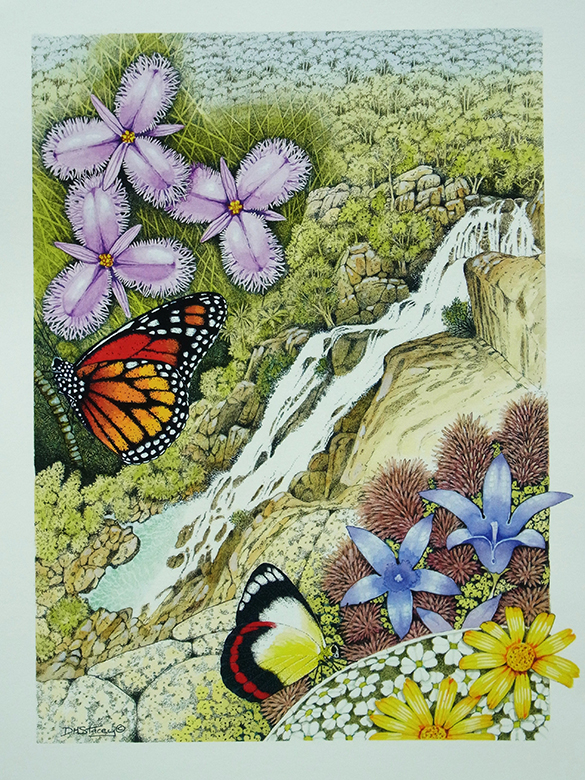

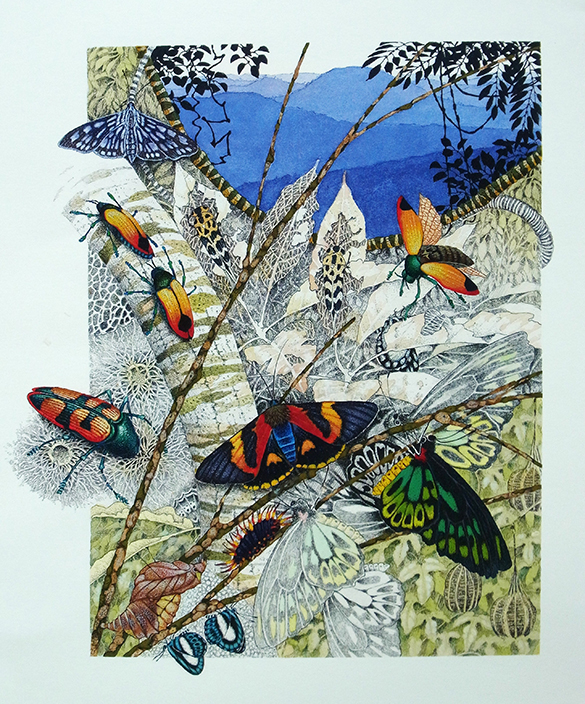

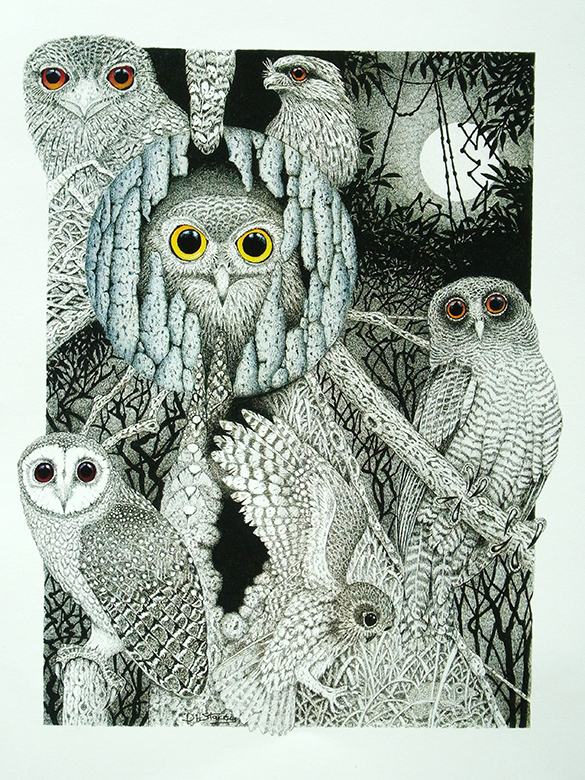

My first impression was that his work lay somewhere between graphic design and picture painting and that the colourful renditions of his rainforest subject matter would appeal to the tourist market and that he would do good business selling his professionally presented greetings cards, prints etc. But there was an element about every work that appealed to something deep within me that kept me looking and kept me very interested. Mr Stacey was botanical artist, landscape painter, scientific illustrator and graphic designer all rolled into one.

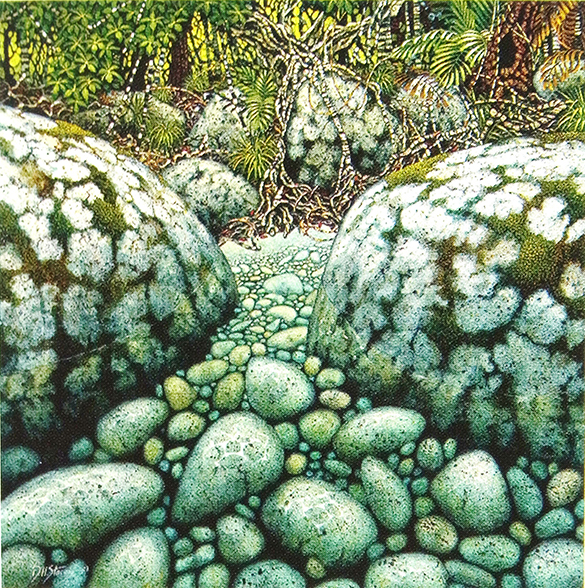

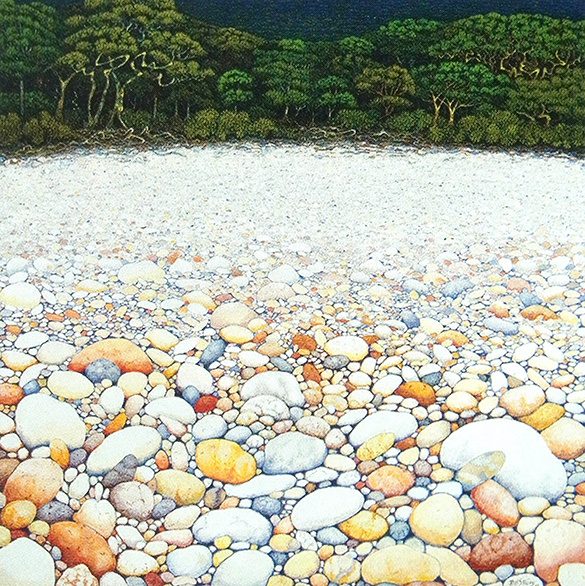

Some of his paintings were conglomerations of maps, landscapes and the creatures and features contained within. I felt that each painting was conveying ideas, feelings, incidents and stories. I was convinced that he was telling of and expressing, in an holistic way, his affinity with, his understanding and appreciation of and respect and love for the surrounding country; particularly the rainforest. I was not therefore surprised that when I eventually spoke to him and asked him what his favourite work was he told me it was the Flaggy Creek Triptych above.

I realised why Mr Stacey’s work was reaching me. Although he does not paint in a strictly realistic style I noted the accuracy of his drawing in his portrayals of different species of flora and fauna; from forest fruits to birds and frogs. I applaud accuracy and this level of it only comes from an intimate familiarity, born of respect and love, for these denizens of the forest. As a student and illustrator of Natural History and familiar with many of his subjects, including some of the landscapes, I believed myself qualified to make such judgements but nonetheless was eager to test my ideas by asking the artist himself.

David, from Sydney, came to Kuranda already a lover of Nature in the 1980s. He confirmed to me that he spends much time in the bush and rainforest walking the tracks and studying the species. He uses a headtorch, like me, to find and encounter the nocturnal species such as the wonderful Waterfall Frog – Litoria nannotis in this painting which coincidentally I went on to photograph at Davies Creek that night after speaking with him! It is no wonder he loves this landscape. Davies Creek is the most gorgeous of places and the habitat of this endangered and beautiful Frog is so well portrayed in his painting.

David agreed that his style was not unlike Aboriginal art in the way that it expresses his world in an holistic way rather than concentrating on a single subject. However he stated that his style had evolved from his personality rather than having been influenced by Aboriginal art. I thought convergent evolution manifests itself in more ways than we think! The Aboriginal and David Stacey both expressing their world by painting it in their own individual way but in a way that displays much similarity.

When I asked David “why do you paint?” he thought for a while then said “what else can you do?” We discussed what he meant by this and agreed that, like me again, he is driven to recreate that which he finds aesthetic; only in his case it is a whole ecology that he has to recreate and thus his conglomerate paintings reflect this. He says that in this modern world he believes that “people are losing their sense of aesthetic and beauty.”

He is a thoughtful man; never answering a question without pause for consideration and whilst reflecting on our interview I later wondered if David Stacey was in his gallery in body but his mind was wandering the rainforest where he was most happy?

David is creating a book with a publisher already very interested. It is an illustrative narrative about the journey of water in a certain creek from source to sea. I was very privileged to be shown some of the plates for the book. It will be unique and quite stunning. It will be for young and old and filled with all the plants, animals, geology, stories and ideas provoked by a long love affair with the natural history of the rainforests of Tropical North Queensland. I shall certainly buy a copy.

David Stacey sells well to the tourists. His limited prints are extremely well produced. This does not devalue his work but I believe that it was not created for this reason. His are works of passion; expressing his world of the rainforest. I think it sells well because it is simply very beautiful stuff about very beautiful stuff.