We’re on a road trip through Scandinavia. It is July. The sun is already high and hot as we breakfast in Copenhagen. Josi and Sari chat about what they will do and see today. I already have a plan. I am meeting an Englishman: and no ordinary Englishman!

Paul Bonner, the famous fantasy illustrator, has replied to my contact email and, to my surprise, has invited me to visit his home. “Why are you so excited to meet him?” asks my daughter who knows my passion for fantasy land (and who adores Littlest Pet Shop and My Little Pony.) “Well…” I explain “I feel I grew up with him. He shaped my interests, pastimes and imagination as he did for millions of people my age.”

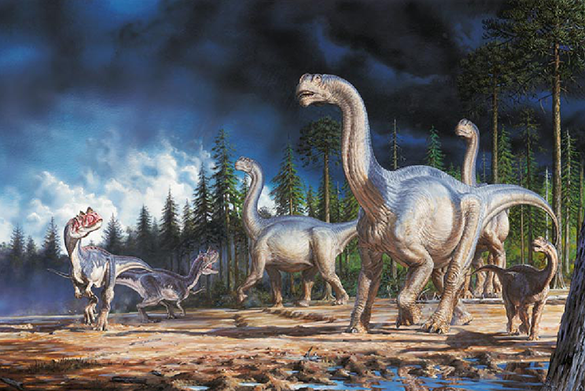

Paul greets me warmly. His handshake is firm. He is not the way-out character that I was expecting. Does this guy’s head really house such an incredible imagination? I register the privilege of entering his personal universe. I see his illustrations for real. He shows and then gives me a book of his work. Mind-blowing! Unsurprisingly, his studio is decked with Asian masks, animal skulls, anatomical posters and model dinosaurs.

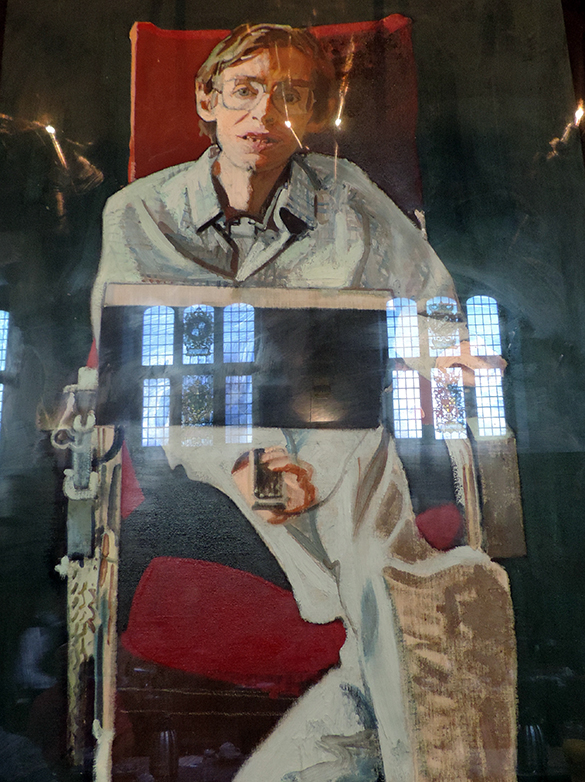

The painting Paul is working on is part of his Beowulf project. It is everything I would expect. A battle-hardened viking-dwarf with drawn sword enters an underground cavern with trepidation. Huge, slithery, spiney, wall-hanging monsters await him. Fantastic fantasy! This is why I wanted to meet Paul.

A beautifully crafted, grotesque and mischievous goblin has pride of place in his studio. It stops me in my tracks. The attention to detail is just remarkable. It looks like it could spring to life at any moment!

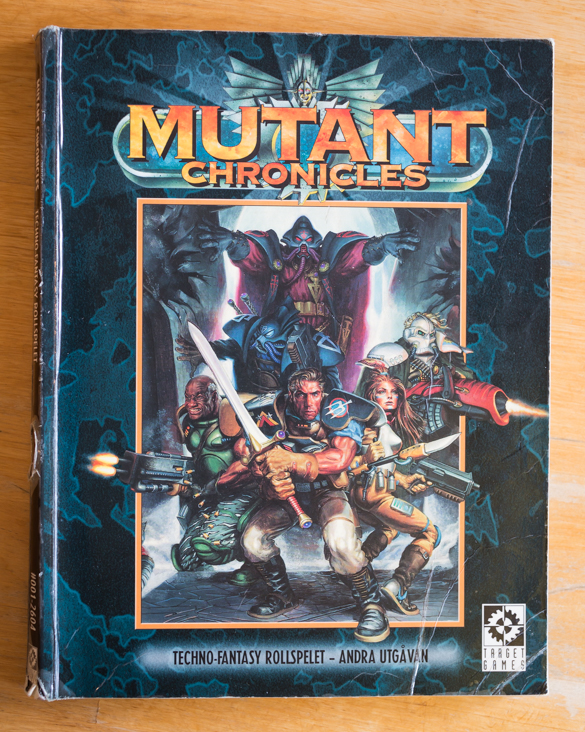

In the 1990s, a company called Target Games (now Paradox Interactive) was working on a series of games set in a dieselpunk, sci-fi universe called Mutant Chronicles. This was before the digital age; it involved a collectible card game (Doom Trooper), three board games (Siege of the Citadel, Fury of the Clansmen and Blood Berets), a tabletop miniature game (Warzone) and a role-playing game (Mutant Chronicles). The cards and booklets required illustrations. Paul, a trained illustrator, was offered the job.

Paul’s muscle-bound, weapon-wielding heroes brought the avatars of me and my friends to life. His imagination fed ours. He seeded and cultivated our fantasy worlds; we could envisage them, step into them and so play out our roles within them. We wanted to stay engaged. We had an insatiable appetite for new avatars. Did his visual depiction of these other worlds and the hundreds of unlikely protagonists ultimately influence the writers?

Paul gives a modest shrug, but as an avid fan of Mutant Chronicles, I have no doubt of the two-way relationship between the writing and the illustration of the game. In fact, a reboot of the role-playing game is in the making, and British publisher Modiphius Entertainment has on Kickstarter promised that the 3rd edition of the “amazing techno-fantasy game” will “reveal never before seen parts of the Mutant Chronicles universe alongside the existing fantastic images by Paul Bonner.” I cannot wait to hear what my friends will say!

Paul’s remarkable career grew from a fascination for Tolkien and Scandinivian fables. No wonder then that he admits to his major influence: the paintings of John Bauer, Akseli Gallen-Kallela and Ivan Shishkin. But then after a holiday walking in Scandinavian forests (probably, I suspect, hoping to glimpse a troll for real) he simply decided to stay and make Copenhagen his base of operations.

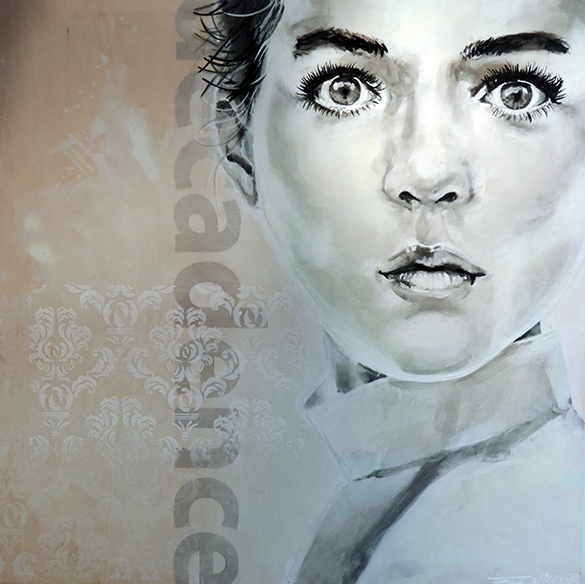

Two hours slip by too quickly. I have made a new friend. In addition, I was able to offer something in return: I advise Paul on how to set up a Facebook page to share his work with fans and friends. Being the master illustrator he is, it is no surprise that his new page already has over eight thousand followers. I cannot help thinking that they would all love to step into Paul’s personal universe as well. I eventually leave and can see that Paul is keen to get back to work. But before you leave this post, take a look at some more of his incredible illustrations. Talk about skill and imagination!