The Musée d’Art et d’Histoire is, as usual, majestic, tranquil and imposing. The difference since my last visit is that my course through the great halls and up the marble stairways is directed by coloured tape, arrows stuck on the floor and helpful staff wearing face masks. I meet Philppa Kundig, the scenographer of the current MAH exhibition “L’infant dans l’art suisse: de Agasse à Hodler.” She has, with curator Brigitte Monti, put together an exquisite exhibition of pictures and sculptures from the MAH collection of works by Swiss artists that feature children and maternity. It is at once informative, coherent and accessible; I am drawn into it to the point that I review the works and texts over and again. However, Philippa and I agree on one thing: there is a single painting that stands out from so much beautiful stuff.

Daniel Ihly’s large canvas “L’enterrement de mon enfant” is stunning. Note: it is entitled “The burial of MY child.” Ihly has portrayed a tragic moment in his own life. However, the funeral procession is set far back in and just entering the scene. The priest and alter boys are followed by the undertaker who carries the be-coffined infant under his left arm. The family – presumably including Ihly and his wife – follow in turn. The most moving element of the whole piece is that he has chosen to place centre-stage not a scene of his own grief but the sincere show of respect by peasants pausing in their work (the closest of whom doubles as a kindly grim reaper.) This allows Ihly to show that the loss of an infant was, in the day, a common and therefore shared bitter experience. I would bet that the girl in the foreground who has brought her father lunch represents for Ihly what the dead infant might have become. The image is perfectly conceived, perfectly composed and technically faultless. Under the circumstances, it is extraordinary in its selflessness. This is one of those rare paintings that grabs your attention from the moment you set eyes on it and leaves an image in the mind that reappears unbidden for days.

The section of the exhibition entitled “The Suffering of Children” makes clear that not so long ago in human existence, a child dying before the age of five was all too common. In June 2020, amid the daily clamour of COVID-19, this section underscores humans’ inevitable susceptibility to infectious disease whether measles, dypyheria, typhoid, pertussis or a novel coronavirus.

These guys could paint! Alexandre Perrier’s image of a seated child convalescing is work of high accomplishment. How can someone put paint on a canvas with the smallest of brush strokes and yet transmit that this kid has been really, really sick; that this is the first time she has been taken out into the garden; that the blanket and cushion had to be carefully placed by a carer’s hands; that she did not do up those buttons; that the daisies were placed into her left hand but failed to glean a flicker of interest; that the grip of her delicate (and superbly rendered) right hand on the wicker chair is as weak as her grip on her young life? Remarkable!

Two other equally well-conceived sections of this exhibition are “Children within family” and “Children in Society;” As a result, the MAH has conjured up a fascinating insight into people’s lives in this part of the world in late 19th and early 20th century; furthermore it serves as a chronicle of how children and parenthood were portrayed according to the rapidly changing outlook of both society and artists at the time. Inevitably, the fourth section comprises that most heavily worked subject in the history of art – “Maternity.”

Wilhelm Balmer’s tribute to the mother and child theme is a small oil-on-board portrait and is of course masterfully composed and executed. Why it catches my eye is that the new mother is not glowing with joy. She is exhausted. Here is a reminder that medical science has not only saved millions of children from the clutches of a variety of microbes but also has made giving birth an experience for the mother that is far less dangerous and traumatic than it was throughout human history.

There is no shying away from the fact that portraits of children of wealthy families were commonly commissioned – and sumptuously framed – at the time. Then what better place than at the entrance to the exhibition to be confronted by the instantly recognisable and impeccable fist of the great Swiss master, Ferdinand Hodler?

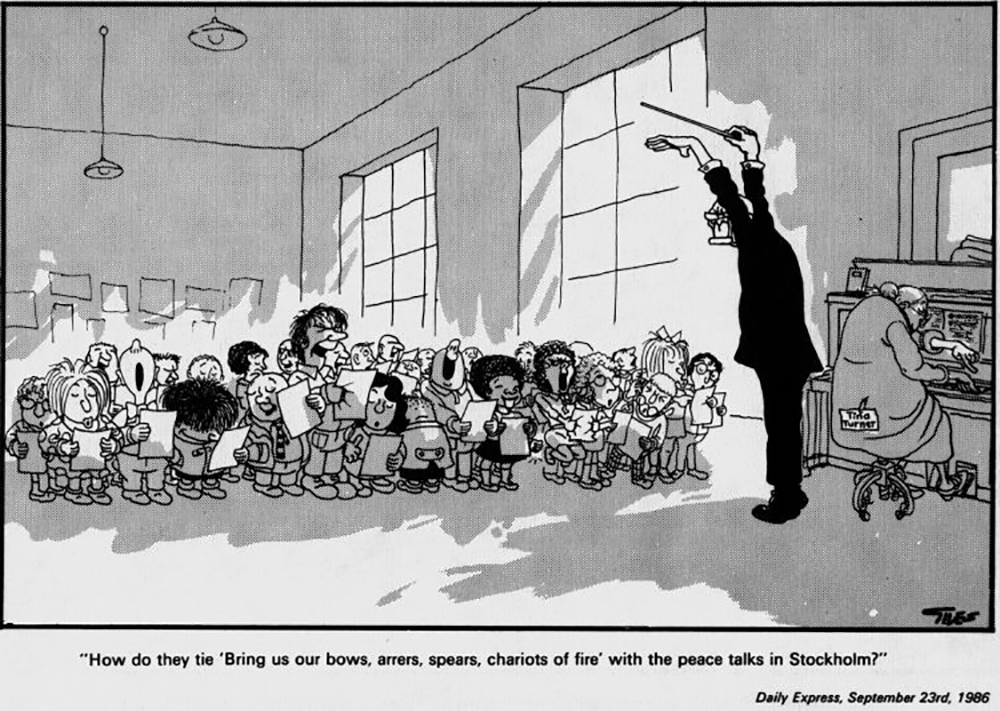

I hope the MAH will forgive me showing here only a detail from a huge painting by Edouard Ravel. A priest tries to inject into a group of children the smallest measure of enthusiasm for their choir practice. Each child shows his or her own degree of diligence, boredom or indifference. Each is portrayed as a character. The scene amuses me enormously. I return to it time and again. My memory banks are jogged…. Surely not? It can’t be!

Yes, I can’t help seeing Ravel’s nineteenth century oil-on-canvas masterpiece as a forerunner of the cartoon. I hope that the MAH will also forgive me for leaving the reader with the work of Giles; another legendary observer of people – and children singing – a century later.