Paulo Tercio contacted Talking Beautiful Stuff to tell us of his admiration of Ana Maria Pacheco. Like her, he trained at London’s Slade (albeit a couple of decades later.) Like her, he creates beautiful stuff that hunts around themes of spirituality, suffering and torment. The first line of his website reads “Paulo Tercio was born into a devout catholic family. His foetus was gestated inside a jackfruit. When his soul entered his body he experienced his first ecstasy…..”

Paulo Tercio contacted Talking Beautiful Stuff to tell us of his admiration of Ana Maria Pacheco. Like her, he trained at London’s Slade (albeit a couple of decades later.) Like her, he creates beautiful stuff that hunts around themes of spirituality, suffering and torment. The first line of his website reads “Paulo Tercio was born into a devout catholic family. His foetus was gestated inside a jackfruit. When his soul entered his body he experienced his first ecstasy…..”

And here it is! Paulo’s painting that depicts what he describes as the single most important moment in his life.

The image is innocent, earthy, nourishing, fecund and more than a little intriguing. Why the seedy head? Why the eye in the foetal belly?

In 2013, Paulo won a commission for a permanent alter piece at St. Andrew’s Church, Fulham. This fabulous work shows the virgin sporting an exquisite orchid and the child whose halo has yet to reach its full iridescence; he casts a sideways, quizzical glance at his mother as if he already knew what life held in store for him. The scene seems to be watched over by two larger and darker forces.

Fascinated by what I find on-line, Paulo and I strike up an email exchange. Why does he works on religious themes? He replies “I believe that, in all major faiths, religious art functions by creating emblems of hope. It has the responsibility to help society in these troubled times.” What inspires him? “My inspiration comes mostly from within. I believe artists should undergo training only to develop their technical skills.” I ask about influences unaware of where this would take me. He begins “Many people have influenced my life including philosophers, spiritual leaders, artists, designers and musicians. Concerning my artworks, I believe spirits of other artists play a huge role in shaping them.” More of his story unfurls. The lines between painting and persona blur.

Paulo says that some of his artworks are transformations of his own suffering. “Collapse of the Ego” is intensely dark, desparate, mysterious and screams in agony. Just read this! “I had a major breakdown a few years ago and I thought life was at an end for me. From working as a manager of a prestigious hotel in London, I ended up in the streets. I was completely broken. I fitted nowhere. Death was my destiny. I gave most of my material possessions, including my own bed, to the homeless. During this time I painted ‘Collapse of the Ego.’ Looking back, I experienced a simultaneous spiritual, physical and mental death. This realisation became apparent a few weeks ago when starting a new painting to be called ‘Metamorphosis & Resurrection.’ I am still living the metamorphic stage: a human being in transformation. My resurrection will be the next stage in my life when as a transformed being I will be able to live life as a newborn.”

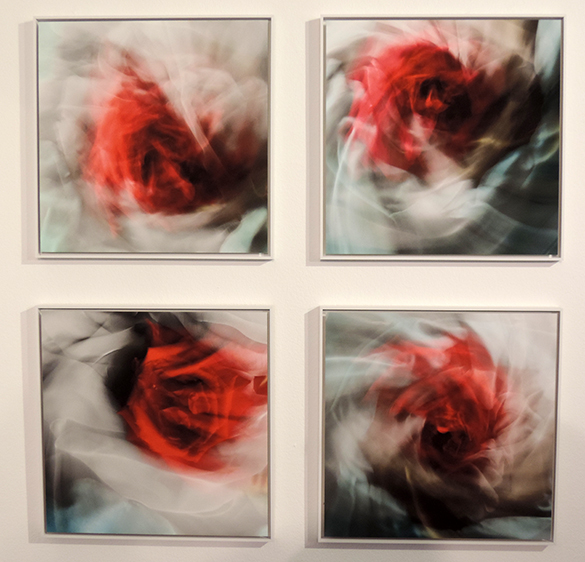

“Plethora of Emotions II” is a beautifully executed but harrowing painting in which mental suffering yells. It has been selected for the “Dreams” exhibition to take place at the Institute of Mental Health in Nottingham (curated by City Arts in partnership with University of Nottingham.) This exhibition will explore the interaction between creativity and mental health. Paulo believes the spirit is intrinsically connected with the mind and that one’s well-being depends on both. He sees his participation in this exhibition as contributing to society more widely. He tells me that with this painting he is attempting to purge the mix of anger, revenge, despair, corruption, guilt and fragmentation that he feels growing inside him. I dig a little deeper and ask him about the source of these feelings. Ready for his reply? “My upbringing ruined my emotional structure. I grew up in a family poisoned by domestic violence. Parenting was abusive and alcoholic. I experienced loneliness, homophobic bullying, persecution, sex abuse, homelessness, and poverty. I felt desolate. Self-loathing and isolation were my main sources of escape as any attempts at artistic expression were met with contempt. ‘Plethora of Emotions II’ portrays a human being overpowered by collective emotions. Despite all this my religious roots, if anything, made me a more compassionate and humble person.”

So, Paulo, thank you for letting us see into your creative universe. And thank you for telling us about your ecstasy and for sharing your agony. I am sure all the readers of Talking Beautiful Stuff wish you well.

Talking Beautiful Stuff thanks Paulo for his permission to publish extracts from his email exchange with Robin. Portrait photo of Paulo Tercio © BvB Universe