I had the good fortune to be invited to Art Club Puplinge by Victoria James (who lives in Puplinge!) For me, a lapsed painter, it was both fun and inspiring. I will go again.

I didn’t know what to expect. Before leaving home, I threw into a shopping bag some coloured inks, a box of neocolor crayons and, for reasons unknown, a map of the London Underground. Would we be given free rein to do what we want or did Victoria have a cunning plan for us? As it turned out, Victoria had a cunning plan that involved us doing what we want. Brilliant!

Our session started with the group doing brief “blind” portraits of ourselves or each other without looking at the paper. I squirmed inwardly. This was not in my comfort zone. Little did I know that it was part of Victoria’s cunning plan.

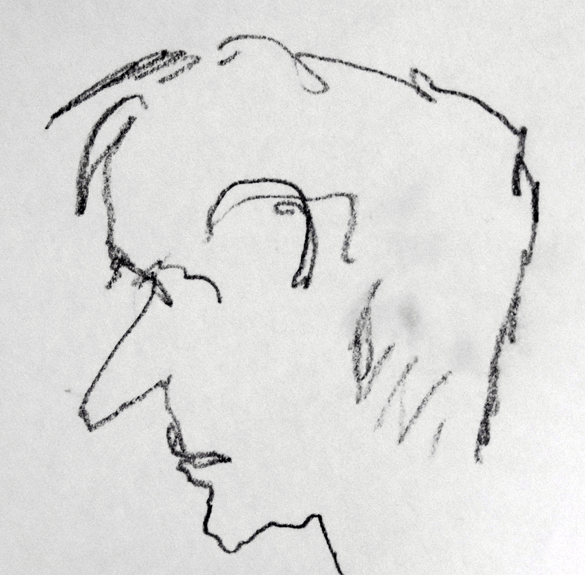

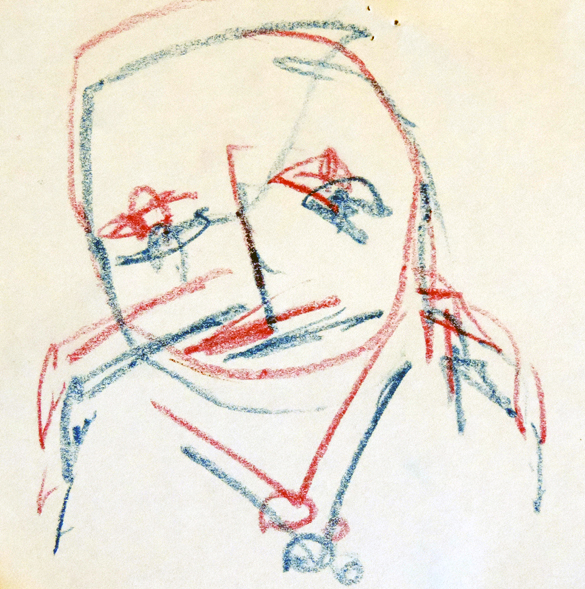

One of my new friends managed this alarming likeness of me in just twenty seconds!

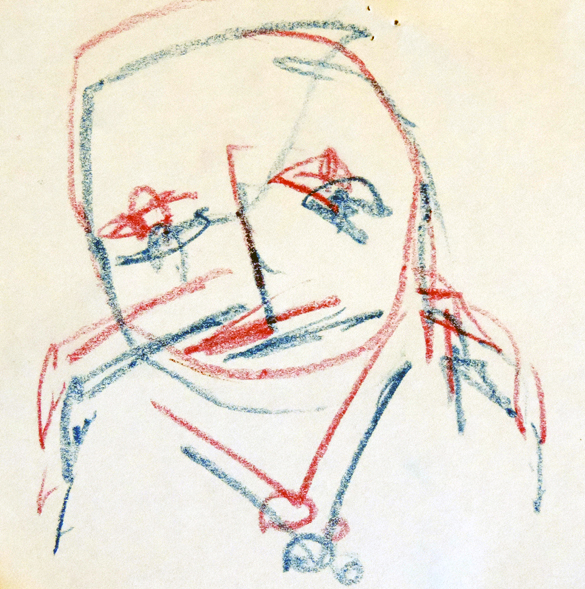

Here’s my best attempt at revenge holding two crayons together!

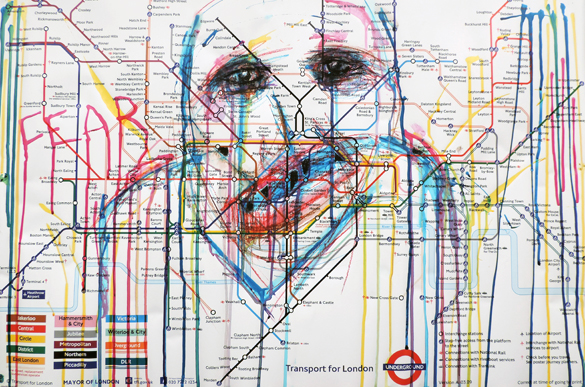

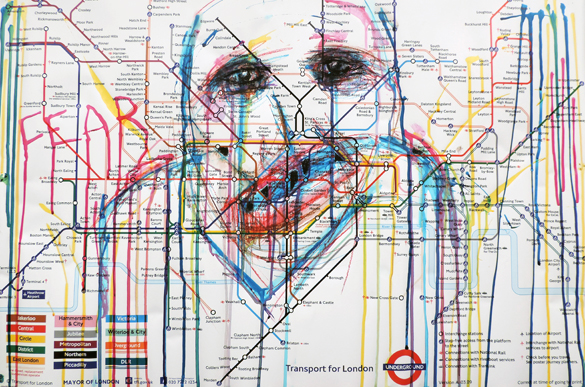

One hour and twenty such quick drawings later, I found that I was not back in my comfort zone but in a comfort zone that was new to me. I was enjoying it. I was squirm-free. Interesting! This of course is also part of the plan and sets up the second half of the session. We then selected one of the sketches as the basis for something more ambitious on a larger scale.

I am not sure at what stage or why a scaled-up version of my little blue-pink-dash-double-crayon portrait surperimposed on the map of the London Underground invoked a feeling of fear. I admitted this to Victoria. “Go with it!” she said. And so I did! It may not be beautiful and it may not be “art” (whatever that may be!) But if you had told me thirty minutes beforehand that I was behind the creation of this frightening bazingo image, I wouldn’t have believed you.

Victoria’s objective of the wonderfully informal two-hour sessions at her Art Club is that her guests find and recognise that creative part of themselves the existence of which they are unaware. She tells me that everyone has a bit of creative software loaded on their mental hard drive although, for some, it may be tucked away in a password-protected programme. She can usually help a guest to find it whatever their age.

Victoria trained in London at the Chelsea College of Art with a focus on sculpture. She wins me over by agreeing that the creative forces of humanity might flourish more widely if the word “art” was not used to denote something exclusive. In this vein, she looks slightly ill-at-ease when describing her former career in the world of “contemporary art.” She won considerable recognition for her video-installations which, at the time, were “what one did” if one was in the progressive London art scene. By her own admission they were “out there.” Then, eight years ago, she quite simply stopped. It had ceased to be creative. She took to sports massage, a domain in which she has also been successful. Only in the last months has she found herself drawing again. Her own creative hard drive was re-booted. The result, happily, is Art Club Puplinge. Join it! You’ll have a ball! You’ll also leave each session feeling rather liberated and with an insight into the programming that supports your own creative abilities.