A weekend in Paris with friends! We have tickets to visit the biggest ever collection of works by Leonardo da Vinci. Brimming with anticipation, we head off to the Musée de Louvre. The famous glass pyramid sparkles in the light of a crisp January morning. Quelle bonheur! I want to experience up close two of Leonardo’s works that represent the wide range of his extraordinary achievements: a tiny drawing of a hand-cranked helicopter and, of course, the Mona Lisa.

We queue to go through a metal detector and to have our bags x-rayed. We queue to show our tickets. We queue to pay for an audioguide. With the receipt for the payment for the audioguide, we queue to pick up the audioguide itself. We are given a hasty explanation of how it works. Apparently, the numbers of the 179 works on display do not correspond to the numbers of the 22 works featured on the audioguide. We enter the exhibition a tad confused and with spirits a little dented.

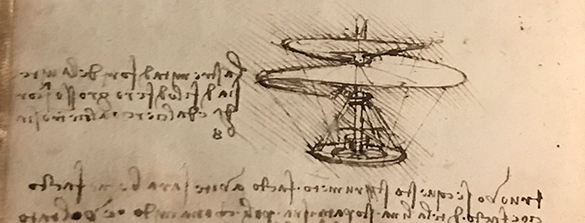

The free exhibition catalogue is helpful in explaining the phases of Leonardo’s life (that ended 500 years ago), his influences, his interests and his techniques. The Louvre’s chosen approach is very academic and presents the works in four not entirely coherent sections: “Light, shade, relief,” “Freedom,” “Science” and “Life.” With respect to the paintings, there are few complete works (because Leornardo completed so few!) There are many studies executed in chalk or ink. There are also fascinating infrared reflectograms – an imaging technique that traces the carbon of the drawing beneath the layers of coloured paint – of his better known paintings. The section on “Science” makes manifest what puts Leonardo da Vinci in a class of his own. His truly beautiful drawings and hall-mark mirror writing reveal an inquisitive technical mind and a profound comprehension of worldly things. He was way ahead of his time. He mastered anatomy (which meant he dissected dead bodies.) He mastered geometry. He mastered chiaruscuro – the drawing of light and shade. He observed and drew strata in rock formations, the growth of trees, the nature of waves and fluid mechanics. He imagined and designed numerous machines and buildings.

Regrettably, I am unable to say whether the Louvre is successful in making the oeuvre of this towering genius accessible to the exhibition-goer. Why? People! The place is heaving. Like hundreds of sheep we shuffle around shoulder to shoulder all trying to get a view of the great master’s works. It’s impossible to take a quiet moment to appreciate them. And… merde! … every picture has hands in front of it all manipulating smart phones. The works that feature on the audioguide are obviously those that draw most interest – and most smart phone photography! Further, the audioguide number is displayed so low on the wall that it can be difficult to find through the press of twenty-first century humanity. It is not always clear precisely to which work or works the audioguide is referring. In brief, the exhibition is a chore. Add the crush of people and the experience is an exercise in frustration with little to reward us for having braved the current French transport strikes to get there. And I’m sorry to say, the news gets worse.

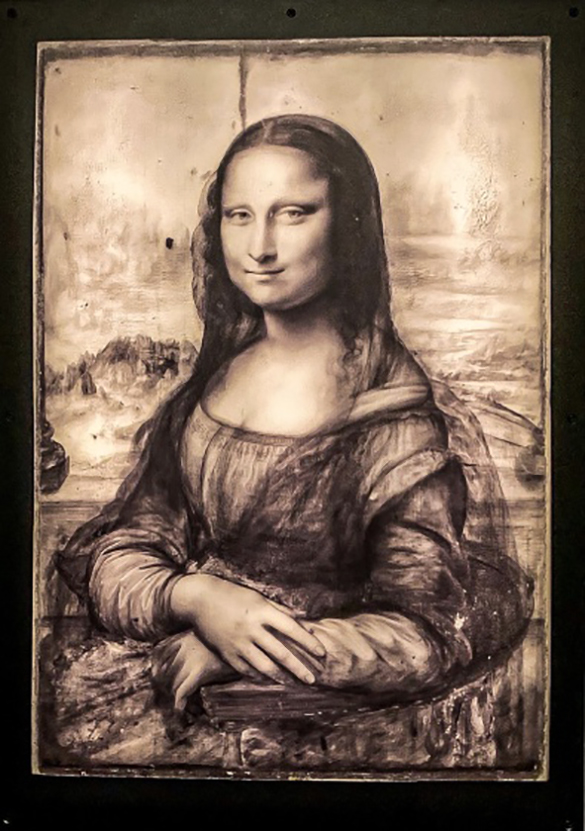

Isn’t it reasonable to expect to see the Mona Lisa at this exhibition? She is, after all, housed permanently in the Louvre. Wouldn’t you think that the infrared reflectogram of the Mona Lisa is a foretaste of what must certainly be awaiting us in the last room? Inexplicably, the audioguide when describing the sepia toned infrared reflectogram refers to the colours of the Mona Lisa’s lips and skin in the conditional tense. Most bizarre of all, the narrative ends with “The real Mona Lisa belongs to the King of France and to see it you have to go to Fontainebleu.”

Having queued to return our audioguides, we head off to a nearby bistro for lunch. We admit to each other that the morning was not what we were hoping for. We agree that the absence of the Mona Lisa is both a surprise and a disappointment. We also concur that the audioguide really did make reference to the world’s most famous painting belonging to the King of France! Is there still a King of France? But then, on examining a casually picked up museum brochure, we see that the Mona Lisa is still displayed at the Louvre but in a different wing several floors up. Obviously, the Louvre wants her to remain viewable by the broader public but nothing indicated that she would not be part of the dedicated Leonardo exhibition. Communication 101! So we decide to return and, inevitably, we join the longest queue of the day to stand for 30 seconds in front of her. And of course, it’s Mona Lisa selfie time.

It saddens me that the works of one of the greatest minds ever in one of the greatest museums ever can be exhibited with such mediocrity. The exhibition closes on 24th February. Don’t join a brawl for remaining tickets.