Tate Britain bowls me over again. In one hit – in retrospect, a mistake – I get to take in the work of Vincent Van Gogh and Don McCullin with Mike Nelson as the bonus prize. These three stunning exhibitions could not be more different. I only have the morning. I move through them perhaps too quickly; the resulting cocktail of emotions takes me surprise.

Van Gogh came to London in 1873 at the age of twenty; he lived here for three years. England and english people inspired him; when his work became well-known, he in turn inspired English writers and painters.

Long after leaving England, he painted a prison exercise yard. This was inspired by a fascination for London’s seedy underbelly and descriptions of the city’s prisons by Charles Dickens: a writer whom the young painter admired greatly.

Years after his death in 1890, Van Gogh’s work was labelled “post-impressionism.” Some found the style shocking but exhibitions of his paintings in London drew thousands. The hall-mark brushstroke technique was eagerly adopted by the Camden Town Group of painters.

Soothed and enchanted by Vincent’s starry, starry night, I believe myself ready for Don McCullin. Wrong again!

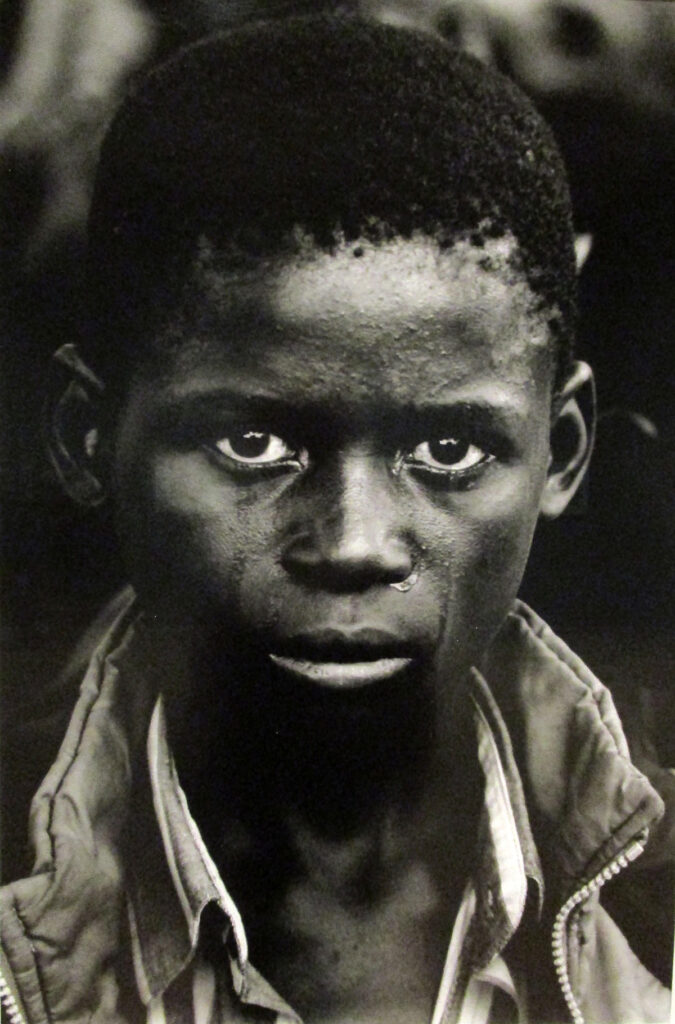

Don McCullin is a legend. This comprehensive show covers his extraordinary sixty-year photographic trajectory through the world’s worst trouble – misery spots. There is a reason that the Tate has an advisory notice pertaining to his images. Much of the subject matter is heart-wrenching; the outstanding quality of the (self-printed!) photographs only serves to make them more powerful still. And there are hundreds of them. I recoil from the man-made suffering, the executions, the starvation and the dead bodies. It cuts just that bit close to my bone. I notice that the many viewers fuse into a sort of silent, shuffling, heavy-weight-around-neck chain gang tasked with looking at McCullin’s photos. Some of us loiter around his own escapism in the relatively few but exquisite landscapes and still-life studies.

I confine my focus to his portraits. Even these can be harrowing. Probably the best known is the Vietnam shell-shocked American soldier of whom he took several photos and who neither moved nor blinked over several minutes. In the trade, this is known as the “thousand-yard stare.” McCullin admits that receiving praise for photographing the suffering of others sits uncomfortably in his soul.

I try – and fail – to imagine how McCullin has been able to cope with the extreme insecurity and distress inherent in his chosen contexts and then function professionally and creatively. I leave this landmark exhibition steeped in admiration for the man, his endurance, his compassion and for what he has achieved with his talent.

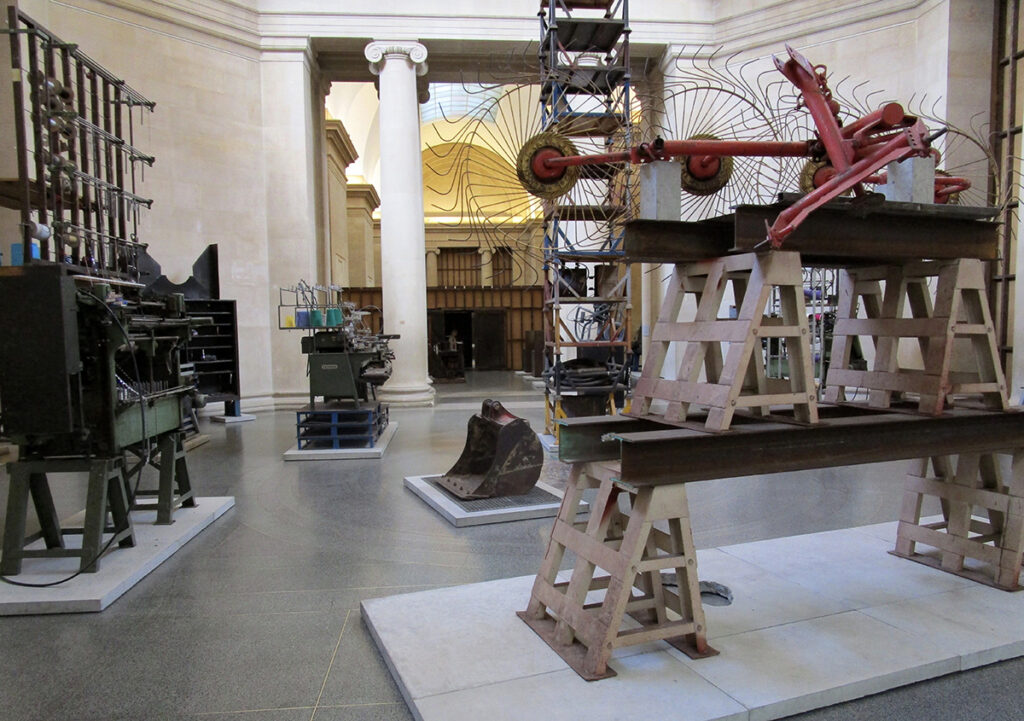

I literally stumble into the Duveen galleries; the main central space of Tate Britain. I am looking at some old telegraph poles and a section of a wide concrete pipe laid out on some canvases all in a kind of makeshift roofless shed.

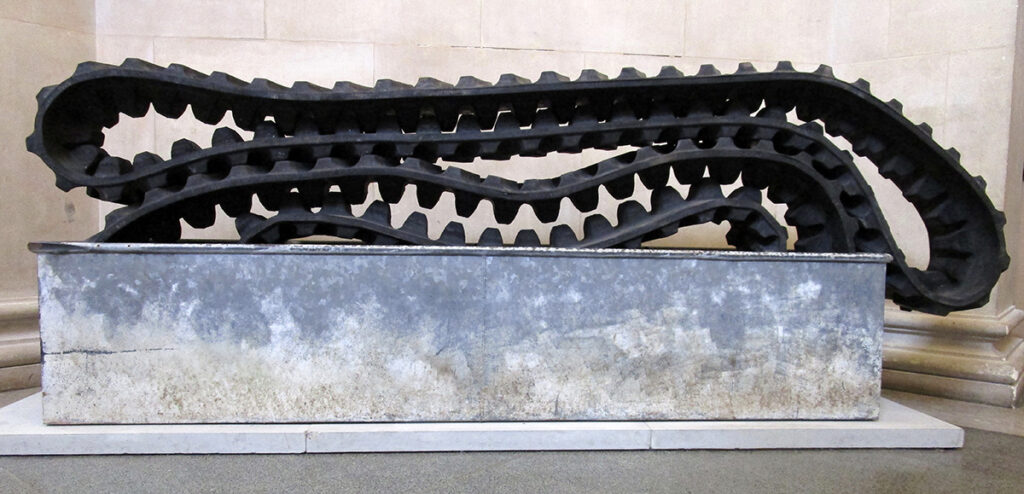

The galleries are full of old machinery and a variety of heavy objects mostly associated with manufacture. Everything sits on a neat stone plinth. Is it an industrial museum? Is it a contemporary installation? Is it a tongue-in-cheek collection of big old heavy mechanical and electric stuff. Well…. all of the above! And what’s more, it contrasts rather deliciously with the classic architecture of the space. What I am standing in – and enthralled by – is “The Asset Striipers” created by Mike Nelson for the annual Tate Britain Commission.

Nelson’s concept for the commission is that the Duveen Galleries become a kind of warehouse of objects that serve as monuments of Britain’s former industrial wealth just as the industrial is being superceded by the digital; as manufactrure is being superceded by service. To make the point, he selected and purchased all the objects through on-line auctions of asset strippers and company liquidators. I find the concept at once brilliant and intriguing.

Then suddenly I am drained. I feel as though I have just climbed off one of those roller-coaster rides that is supposed to be fun but, in reality, precipitates spells of wheeeeee… and white-knuckle nausea. I head for the main exit with a haste that surprises me. I find calm on Millbank; the black taxis, the River Thames and the unseasonably warm May London sunshine.

All images reproduced here thanks to Tate Britain.